Painting and sculpture may fetch the highest prices and become the most renowned artworks, but the humble medium of drawing has been crucially important in art history, if often operating behind the scenes. The King’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace aims to raise the repute of works on paper with “Drawing the Italian Renaissance,” a major exhibition of examples from one of the most famed periods in the history of art, opening in November.

Bringing together 160 works by more than 80 artists who lived between 1450 and 1600, the show will acquaint visitors with the draftsmanship of titans like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Titian, as well as lesser-known names. The gallery promises the “widest range of drawings from this revolutionary artistic period ever to be seen.” They aren’t overselling. In addition to iconic works from the aforementioned masters, the exhibition will include 12 drawings that have never been shown in the U.K., and more than 30 from the Royal Collection that have never been shown to anyone, anywhere.

Giovanni Bellini, The head of an old man (ca. 1460–70). © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024 | Royal Collection Trust.

“The Royal Collection holds an astonishing array of Renaissance drawings,” said Martin Clayton, the exhibition’s curator. “These big, bold, and colorful studies show just how exciting the art of drawing became during this time. The Italian Renaissance would have been impossible without drawing—it was central to every stage of the creative process. These drawings cannot be on permanent display for conservation reasons, so the exhibition is a unique opportunity to see such a wide range of drawings up-close and gain an insight into the minds of these great Italian Renaissance artists.”

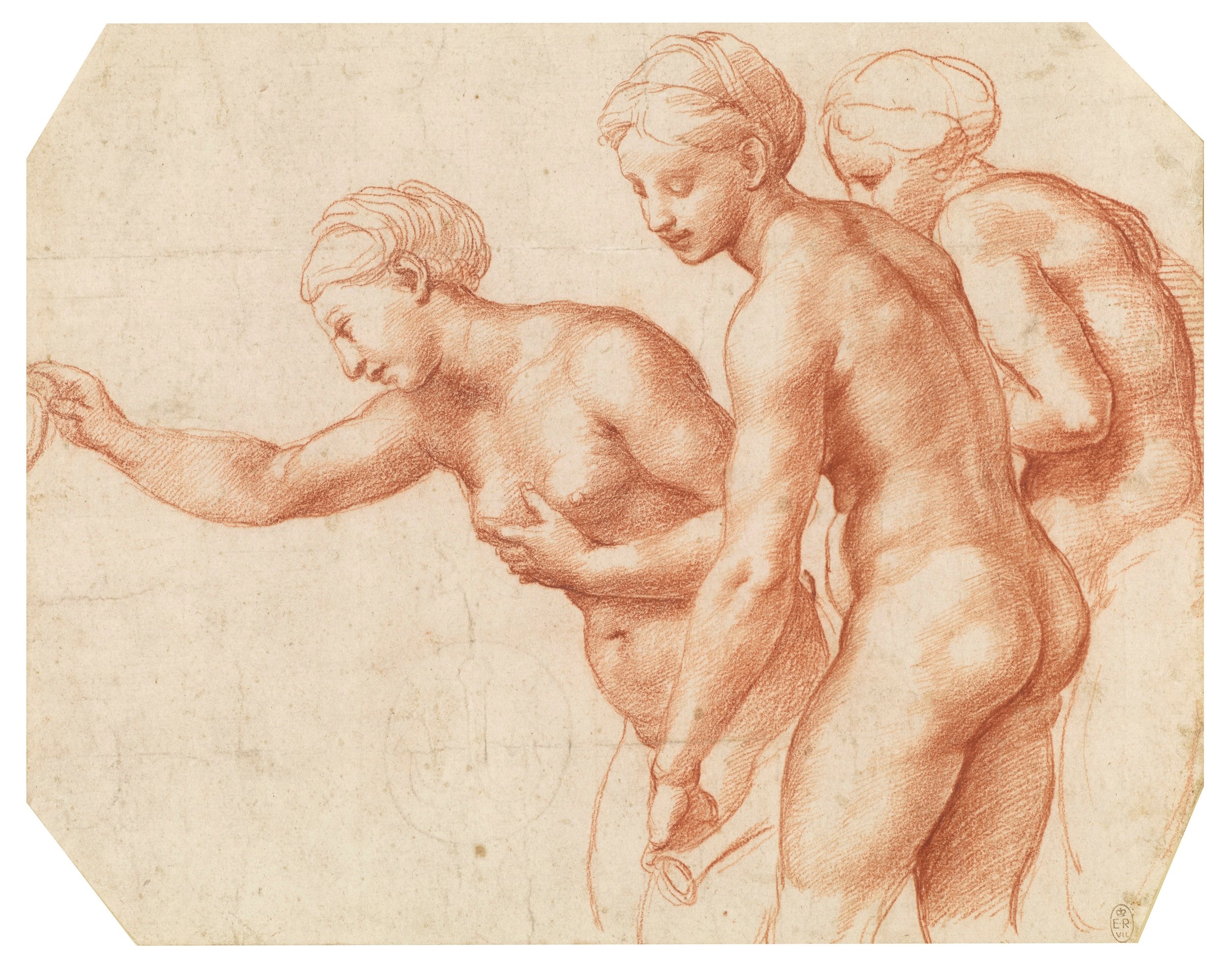

One theme being explored is life drawings. In contrast to artists like Rembrandt, who regularly sketched people they saw in the street, Renaissance artists relied on models formally posing in the studio. Raphael’s chalk drawing The Three Graces (ca. 1517–18) was made in preparation for a fresco, and is one of the few Renaissance drawings made after a nude female model.

One of the oldest life drawings in the show is Fra Angelico’s The Bust of a Cleric (ca. 1447–50), made in preparation for a fresco inside the chapel of Pope Nicholas V in the Vatican. It’s one of the artist’s few surviving drawings.

Fra Angelico, The Bust of a Cleric (ca. 1447–50). © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024 | Royal Collection Trust.

Sacred compositions, including Biblical scenes, provide the show’s conclusion. Here, visitors will find Michelangelo’s 1532 The Virgin and Child with the Young Baptist, showing Mary, Christ, and an infant John, and bearing strong similarities to one of the artist’s earlier, unfinished paintings, The Madonna and Child with St John and Angels.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Virgin and Child with the Young Baptist (ca. 1532). © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024 | Royal Collection Trust.

Among works shown for the first time is a chalk study of an ostrich, made around 1550 and commonly attributed to Titian. It’s drawn in the style of the artist’s native Venice, and the implied movement of the image suggests that he drew the animal from life at the courtesy of one or other republican princes, who were known to receive exotic animals as gifts from foreign emissaries and trading partners.

Another first is Paolo Farinati’s untitled study of three mythological figures under an arch, dated to roughly 1590. Farinati included an inscription to his assistants, apparently giving them some artistic license: “You may do it as you fancy when you are on the scaffolding.”

Paolo Farinati, The Goddesses of Fruit and Agriculture, and a Personification of Summer, ca. 1590. © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024 | Royal Collection Trust.

For art historians, these drawings can be just as valuable and interesting as the paintings and sculptures that resulted from them. In addition to their technical quality, they reveal how the artists evolved and experimented, how they worked and reworked compositions, and how they identified and solved creative problems. They spoke of terms like “primo pensiero,” the first idea or draft, created quickly and instinctively, and “modello,” the more polished proof of concept they presented to their patrons.

Drawing remains foundational to many artists’ practice today, and three artists in residence, appointed in cooperation with the Royal Drawing School, will set up shop in the galleries so visitors can get an idea of how the works on the walls were created. Not only that—they can even get into the game themselves, creating their own drawings with pencils and paper provided by the gallery.

“Drawing the Italian Renaissance” will be on view at the King’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London, from November 1, 2024 through March 9, 2025.