Welcome to Buy, Sell, Hold, our weekly column where we survey the art market, crunch the numbers, and discuss which artists to buy, sell, or hold based on an analysis of a combination of big data drawn from artnet Analytics as well as a spectrum of events such as current, recent, or upcoming exhibitions, art fairs, buzz, buying patterns within the industry, aesthetic trends, and that unquantifiable something in the air.

Time to Sell: Prints by Paul Gauguin

When the idiosyncratic collector and reclusive heir to a timber and oil fortune Stanley J. Seeger put his collection of 10 top-tier Gauguin prints up for auction at Sotheby’s London in 2011, the results put the art world on notice. The top lot, a traced monotype with crayon of a crouching Tahitian woman, sold for $925,970 (more than tripling its low estimate of $288,739) setting a new record for the artist’s prints at auction. The entire group of monotypes, traced monotypes, and woodcuts (the three most important types of prints made by the artist) sold for $2.47 million. The Seeger sale coupled with the sale the year before of the traced monotype Trois têtes tahitiennes for $387,033 (more than triple its low estimate), at Sotheby’s Paris, seemed to indicate that there was a run for Gauguin prints. Now with the hopping success of “Gauguin: Metamorphoses,” an exhibition of prints at the Museum of Modern Art, it seems it’s a better time than ever to put your monotypes on the market.

This isn’t the first time that the market for Gauguin prints has been heady. According to Mary Bartow, vice president of Sotheby’s print department in New York, prints by this modernist master were doing incredibly well in the ’70s and ’80s and then dropped off. Looking at the artnet Price Database, the 1988 sale of L’esprit veille (Tahitian Woman with Evil Spirit) at Sotheby’s London for $571,640 seems to support that view. That it was within its estimate of $556,792–$927,988 shows that expectations were likewise high.

These days, the best quality Gauguin prints rarely come to auction, and when they have, at least in the last few years, it has caused a feeding frenzy. This is partly due to their rarity. There are limited high-end Gauguin prints in existence and fewer in circulation on the market. A quick look at the wall texts at the MoMA show reveal most of the prints have been snapped up over the years by institutions like the Art Institute of Chicago and the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. But there’s still room for the individual connoisseur.

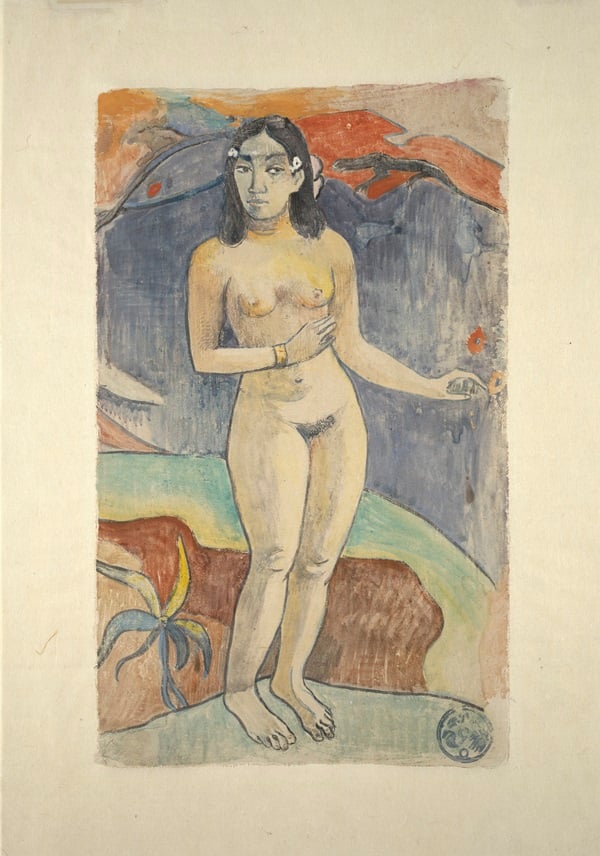

Paul Gauguin (French, 1848–1903). Nave nave fenua (Delightful Land) from the suite Noa Noa (Fragrant Scent). 1893-94. Woodcut, comp. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Rosenwald Collection

While museums were vying for the booty at the Seeger auction of 2011, that sale saw two “very eager private collectors,” according to Bartow: one American and one Southeast Asian; one who has been collecting prints for a while, and the other new to the print market. One of the private collectors, who ended up buying most of them, has loaned them to the MoMA show.

Collectors of Gauguin prints, which could include rough-hewn woodblock prints, vivid watercolor monotypes, oil transfer drawings, or zincographs (lithographs printed from zinc plates on bright yellow paper), tend to be more sophisticated than your average print connoisseur. “Much more goes into understanding how these were made and the variations in them,” said Bartow. “So he’s not necessarily appealing to the people who are buying Warhols and Lichtensteins.”

With respect to his woodblock prints, Gauguin had a practice of printing works in “states,” or when the woodblock was in varying degrees of completion. This means a work in a later state would have more detail and finer lines. While the first state of Nave nave fenua, a print series from the Noa Noa suite (1893–4)), shows an image of a Tahitian woman by a stream in a tropical jungle, the second state shows the same image but with a decorative border suggestive of a Polynesian totem. Others in the same series are printed on pink paper, while still others have been printed multiple times over the original impression in varying colors to add depth and mystery to the final work. Though printed in editions of about 20 or so, each was, in its way, unique.

Paul Gauguin (French, 1848–1903). Maruru (Offerings of Gratitude) from the suite Noa Noa (Fragrant Scent). 1893-94. Woodcut, comp. Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Mass. Photo by Michael Agee © Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts

Interest in the prints may be high once again, but they’re not coming up as frequently as they did in the 1980s. Neither Christie’s nor Sotheby’s has managed to get any Gauguin prints for their upcoming print sales in April and May, though Bartow says she is working on a set for the fall sales.

The supply on the private gallery market, which tends to correspond to public sales, is apparently just as scarce.

“I haven’t had an impression like a hand-pull by Gauguin in quite some years,” said Armin Kunz, director at CG Boerner, a leading dealer in European old master, 19th century, and modern prints and drawings, who nonetheless agreed that the market for Gauguin’s prints is currently very strong. “It’s not a regular occurrence. We’re not talking Rembrandt or Goya. It’s not like there’s one dealer who has oodles of them.”

Kunz noted that another obstacle for private collectors wanting a monotype is that collectors who have been amassing works like this tend to donate them to institutional collections, as happened in 2002 when Edward McCormick Blair Sr., trustee of the Art Institute of Chicago, donated his collection of 41 drawings by Gauguin to that institution, making it the largest gift ever of Gauguin drawings to an American museum. He noted the “pocket” of works on offer to the public at the 2011 Seeger sale was a bit of an anomaly.

“When prices kind of peak,” he said, referring to that sale, “that often means there’s more material coming up. But that actually hasn’t happened. Which in a way is proof of how rare it is.”

According to artnet Analytics, in 1987 the total sales value for Gauguin prints and multiples was $96,079; in 1988 it was $1.2 million; in 1989 it was roughly $200,000; nearly $800,000 in 1990 and 1991; and back down to around $200,000 in 1992. In the late 1990s (from 1997–2000) the global sales volume for Gauguin prints and multiples was above $1 million. Although it remained in the upper six figures from 2001 to 2003, it became erratic thereafter, dipping in 2004 to $102,704, reaching $818,782 in 2006 and coming back down again in 2009 to $226,189. In 2011, with the sale of the Seeger collection, it was at nearly $3 million, it’s highest level in 20 years.

The dip in the market in the early 1990s wasn’t, according to Kunz, exclusive to Gauguin prints. When the Japanese market bottomed out, there was a flood of material on the market. “Jasper Johns’s Double Flag, which sold for $450,000 in the late 1980s, suddenly you could buy for $150,000 or $200,000. But, of course, now it’s at $650,000. So the world is in order again.”