Several prominent French art critics have lambasted the Musée d’Orsay’s blockbuster exhibition on the Impressionist Gustave Caillebotte, titled “Painting Men.”

The show (on view until January 19, 2025) is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to see a large body of the artist’s oeuvre, thanks to exceptional loans. Despite praise, some critics from across the political spectrum argue that the exhibit places too much emphasis on a gendered interpretation of Caillebotte’s work, suggesting he was gay—a point for which there’s little supporting evidence, and arguably, one that shouldn’t matter. These critics also largely attribute this interpretive approach to American perspectives on art.

“The Musée d’Orsay, under the influence of its American partner coproducers, chose to study the painter’s ‘masculinity,’” writes Le Figaro’s Eric Biétry-Rivierre, leading the charge against the gender-themed exhibit in an early review. The show will travel to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and the Art Institute of Chicago (A.I.C.), and was jointly organized by a leading curator from each institution: Paul Perrin at the Musée d’Orsay, Scott Allan at the Getty, and Gloria Groom at the A.I.C.

More recently, a writer at the leftist Libération exclaimed that American-developed gender studies in art history have “crossed the Atlantic and landed,” at the Paris institution. Joined by a third critic at Le Monde, they agreed with Le Figaro, that curators took a “biased” view of the artist’s practice, focusing on his more numerous depictions of men over that of women as further evidence that Caillebotte was gay. This, critics point out, is supported by “suggestive” wall texts throughout the show, featuring some 140 artworks.

In his searing review, Le Monde’s Harry Bellet notes the absence of Caillebotte’s later paintings of flowers. Their “pistils”—the female organs of the flower—”were surely not suggestive enough, or would, on the contrary, contradict the curators’ argument,” he writes. Philippe Lancon, of Liberation, holds little back when he states, “Contrary to what the wall labels heavily insinuate, nothing proves that Caillebotte, who lived with a woman, was gay, and to be honest, it doesn’t matter.”

Gustave Caillebotte Nu au divan (c. 1880) oil on canvas. 129.5 x 195.6 cm. Minneapolis, Minneapolis Institute of art, The John R. Van Derlip Fund, 67.67 Image Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art

Indeed, no information exists about the artist’s sexual orientation, and the curators have repeatedly said no conclusive information was found on the topic. Nevertheless, the ensuing, rather jumbled debate has brought the question further to the fore, suggesting that to some degree, it does appear to matter after all.

The exhibition’s introductory texts state that the artist made unusual depictions of men for his time, often bachelors captured in domestic, intimate settings typically reserved for the “women’s sphere” in the 19th century. “It is these subjects and that ‘gender trouble’ (as the philosopher Judith Butler put it), that give the artist’s work much of its vital tension and subversive power, which this exhibition and its catalogue seek to explore,” reads the show’s press release.

In interviews, the catalogue, and wall texts, curators vacillate between asserting that we know nothing about his sexual orientation; questioning potentially homoerotic desires on Caillebotte’s part; and stating that he was simply painting his surroundings, which happened to include a lot of men.

The Art Institute of Chicago’s Groom rejected both the notion that the Americans had influenced the French in the show’s making, and that it implied Caillebotte was gay. After reading those accusations in the Figaro review, she told me, “I was amused, because he was saying the Americans inflicted their wokeness on Paris.” In fact, “the idea for this exhibition came from Paris.”

Groom defended the exhibit’s gendered lens, claiming that Caillebotte broke from other Impressionists who regularly painted women (a subject that was easier to sell) and instead showed the male-dominated world around him. His subjects were depicted with stark honesty, whether bathing, rowing boats, lounging on a sofa, or defecating. This was an exceptional, modern approach, deserving of attention, she argued. “His subject matter is very radical during the time, because men were not supposed to stare at men, and he’s staring at men,” she said. “It’s the elephant in the room. It’s what makes him so different.”

She added that several works are “definitely sensuous, [there’s] definitely a gaze, and definitely an appreciation of the male body and the male sportsman, and things that make males male … you can say that. But is that homosexuality? I think that’s a bridge too far,” she said. “He’s looking for a way to come up with a modern form of masculinity.”

Gustave Caillebotte, Raboteurs de parquets (The Floor Scrapers) (1875). Photo © musée d’Orsay, dits. RMN – Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

“The exhibit affirms nothing concerning the artist’s sexuality,” the Orsay’s curator Perrin told me. “However, it does not forbid itself from asking the question: ‘What is the gaze of one man on another man about?’ [and] ‘What is eroticism when applied to the masculine body?'”

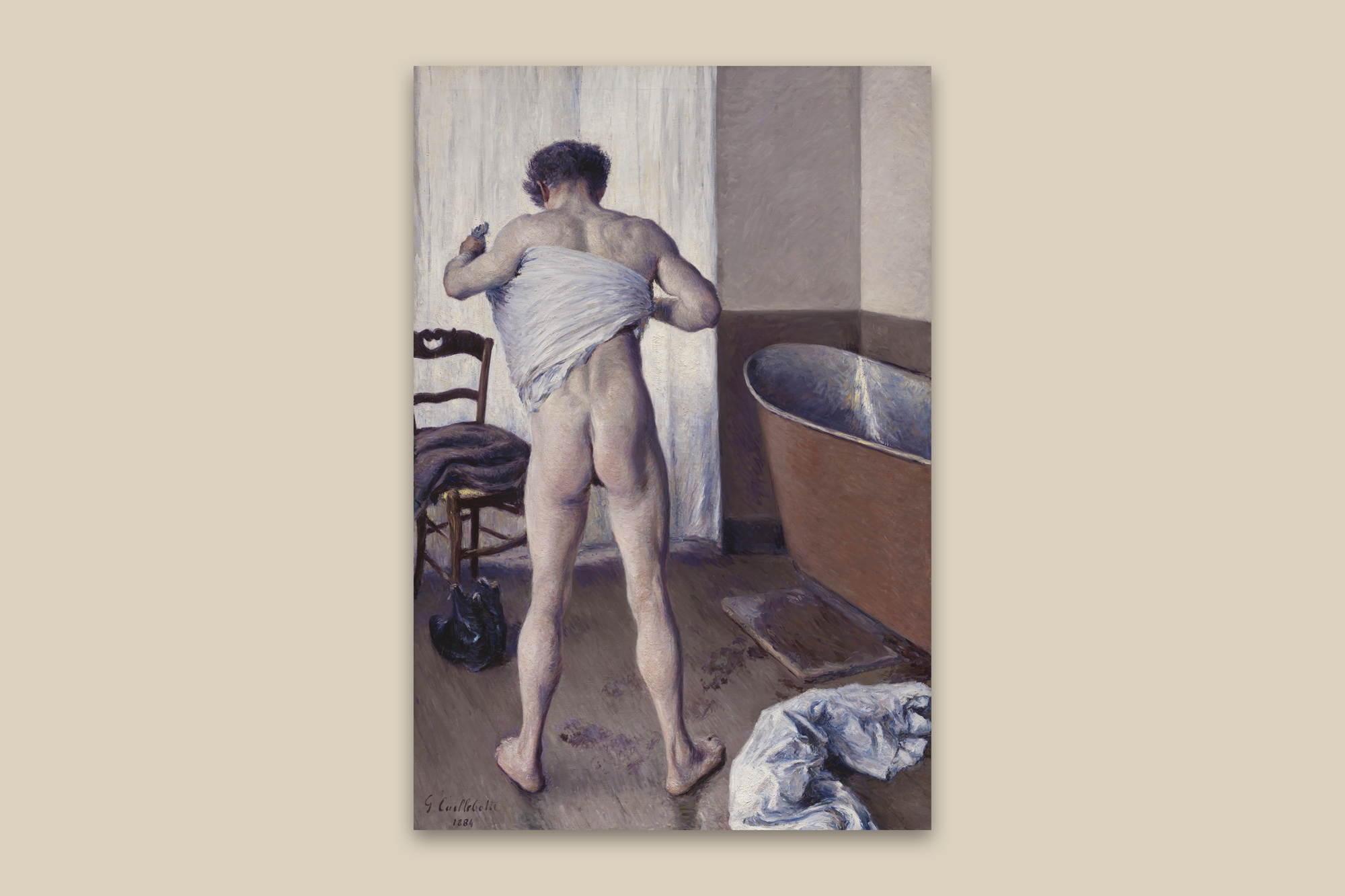

Perrin notes that one section of the exhibition features three major nudes, including a large painting of a woman and another of a man drying himself after a bath, which was inspired by Degas’ depictions of bathing women. In Caillebotte’s unusual rendering, the toned buttocks of the almost life-sized man become the focal point. With this 1884 painting, Man at His Bath, “we evoke that question because the artwork asks us to […] or to put it differently, the question of desire in painting,” Perrin added. “Caillebotte may not have had a sexual preference that he recognized during his life, but it might also not prevent him from having a kind of gaze, in which there is a bit of desire,” he said.

The French curator also felt the Le Figaro article had unfairly put the exhibit on “trial” for referencing gender studies. The discipline “clearly scares a lot of people, because there’s an impression art is being used for ideological purposes, which is not the case here. [Gender studies] is just a tool for modern art historians, which allows us to better understand the artworks.”

He confirmed the exhibit was not influenced by his American collaborators, and that the Paris museum chose the theme, before it was further elaborated upon by the trio of curators from all three institutions. Still, he observed that American art historians have been more interested in the question of gender and sexuality than French counterparts. “I wouldn’t deny that there is an Anglo-Saxon art historic influence on ways of looking at painting […] but the United States did not impose anything on this exhibit,” he said.

The show organizers had also strived to offer a fresh take on Caillebotte, who is celebrated for his groundbreaking, almost photographic framing, combined with unusual perspective. But if his framing and composition is so critical, shouldn’t we look at his subjects of choice, asks Perrin? “We’re not here to endlessly repeat the same saintly history of Impressionism. It’s the role of museums to also question artworks and place them in relation to current interrogations, without ever falling into an anachronism,” he said.

Gustave Caillebotte, Le Pont de l’Europe (1876). Oil on canvas. 125 x 180 cm. Geneva Association des amis du Petit Palais, 111 © Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

Some of the exhibition interpretation does go way out on a limb when describing imagined narratives in some of the paintings. For instance, in the iconic painting showing one of Paris’ new, industrial bridges, Le Pont de l’Europe [The Europe Bridge] (1876) a man walks towards the viewer, said to be a self-portrait of the artist. He turns back slightly to a woman walking just behind and to his left, but he simultaneously glances at a man in front of him, who is leaning over the bridge railing, admiring the view. “Has the man just accosted a sex worker?” the show’s label asks, apparently in reference the woman in the painting. “Is he not, in fact, more interested in the worker towards whom his gaze seems to be directed …?”

Such questions are scattered throughout, adding confusion to the compelling thesis the curators have expressed in interviews and in the catalogue. Namely, that Caillebotte painted men differently than his contemporaries did, just as he painted women differently, for that matter, with an extraordinary, and unmatched modern lens. One that strove at all costs to convey with honesty the life he experienced around him.

Gusave Caillebotte, Boating party also called Rower in a Top Hat (Canotier en chapeau haut de forme) (1877) Private collection Photo by Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images.

It was a vision that considered men in all states and forms, including what would be considered flattering at the time, or not at all, making for an unlikely subject of a painting. It was also a risk Caillebotte could take. Born into wealth, he did not need to sell his paintings to make a living. Thus, male subjects can be found lounging and reading literature on sofas, in what are considered more “feminine” activities for the time, per the exhibit, or as more “manly” men: rowing boats, or else as soldiers bored or relieving themselves.

These men are also painted right up close, as in the Boating Party (ca. 1877-78) acquired by the Musée d’Orsay in 2022, where the viewer is positioned near enough to smell the sweat of the handsome man across from them wielding the oars. Caillebotte radically recoded painting genres of his time, and that seems to be the central takeaway the Musée d’Orsay hopes to convey. Unfortunately, it ultimately stumbles in its efforts.