It often feels to the people at the center of a bankruptcy that the universe hangs in the balance of the proceedings. But in the case of American department-store giant Sears, which filed for bankruptcy last October, there is a sense in which that feeling is literally true. Buried within billions of dollars in losses and accusations of mismanagement and self-dealing by Sears chairman and hedge-fund investor Eddie Lampert, the proceedings may help determine the fate of Alexander Calder’s site-specific installation Universe, which defined Chicago’s Willis Tower for over 40 years.

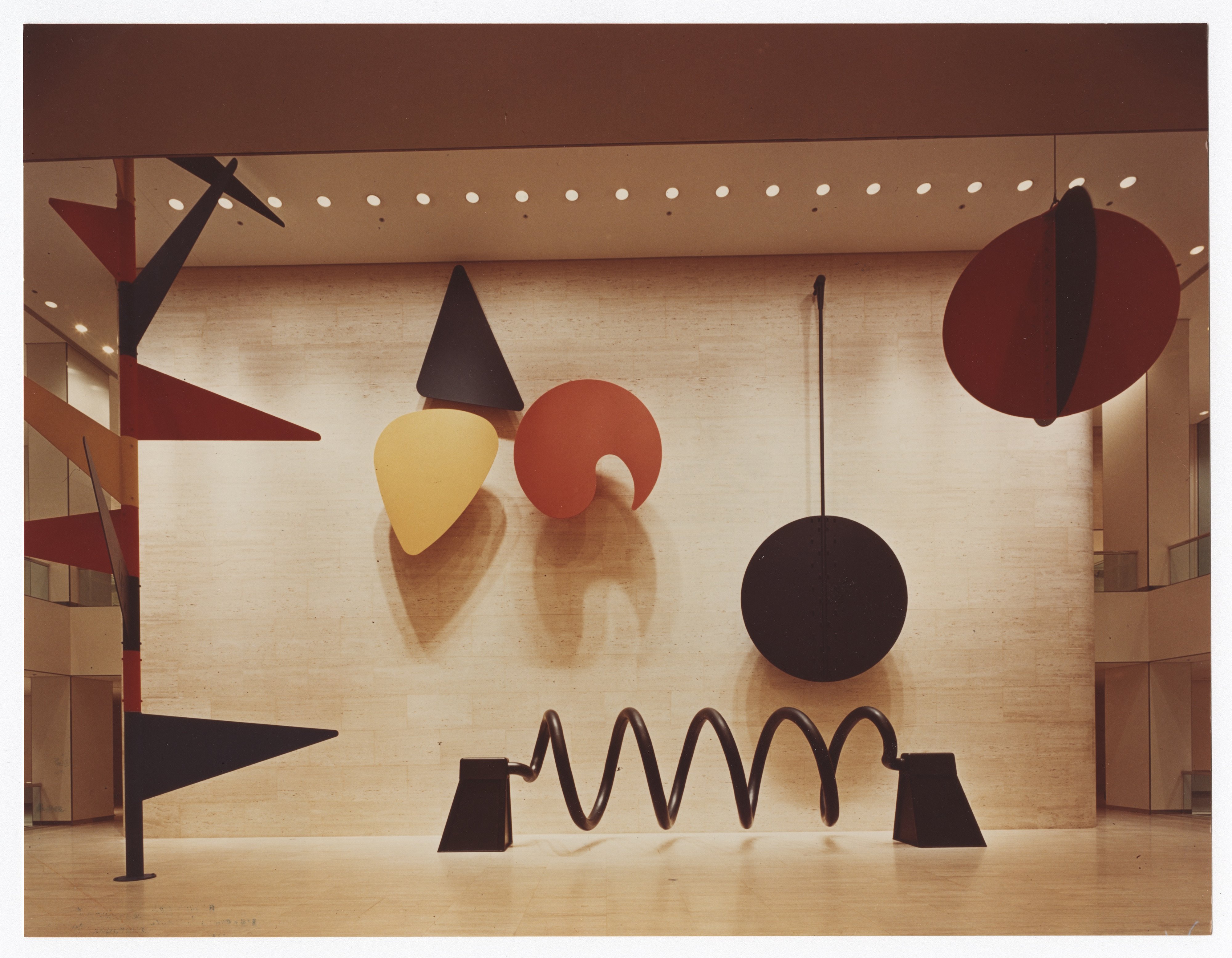

Commissioned by Sears Roebuck & Co. in 1974 for what was then known as the Sears Tower, Universe is a monumental, motorized sculptural installation that reads as vintage Calder. The work consists of five individual components ranging from colorful evocations of the sun and flowers to a massive black helix winding along at ground level. Stretching 33 feet high by 55 feet long and weighing roughly 16,000 pounds, it was designed to deliver an immediate, if whimsical, impact.

However, Universe has now been off view for nearly two years due to litigation between Sears Holdings Corporation—an entity that emerged from the 2005 union of Sears Roebuck & Co. and bargain-retail chain Kmart—and the real estate firm that acquired the tower from Sears in 2004.

Although control of Universe has been unresolved since 2010, Sears maintains that it owns the work. And that ownership claim, in turn, means that the Calder has been thrust into the bankruptcy proceedings along with all other assets owned by the troubled retail titan.

The Willis Tower (center) in downtown Chicago. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Settled and Unsettled

The legal wrangling over Universe is knotty. Although the sculpture was effectively integrated into the tower’s lobby from the start, ownership of the work was governed by a separate “option agreement” created during a 1994 financing deal involving the tower. The option agreement granted Sears the right to purchase the Calder from any subsequent owner of the building for a set fee of $3.625 million, plus interest, during the first six months of 2010.

But when Sears attempted to exercise that option six years after selling the tower to real-estate group 233 S. Wacker, LLC, the latter sued for possession of the Calder. They reached a settlement in 2013, under which Sears earned the right to offer Universe for sale to third parties for two to three years, with a portion of sales proceeds to be paid to 233 S. Wacker, LLC. If a satisfactory offer failed to materialize within that window, Sears would have the option to purchase Universe at a price of just over $3.86 million (the sum of the original $3.625 million plus interest).

Three years later, no offer had met Sears’s liking, and its attorneys notified 233 S. Wacker of its intentions to purchase Universe on June 30, 2016. But the sale did not proceed as planned. Instead, counsel for 233 S. Wacker, LLC asserted that Sears had violated the settlement agreement by refusing a bid of $13.6 million from the real estate firm the Chetrit Group. Sears countersued, noting that two members of the Chetrit Group doubled as managers in 233 S. Wacker, LLC, and that it had the right to accept or reject any offer made for the sculpture regardless.

Another ownership change complicated the matter further. The year before filing the new suit against Sears over Universe, 233 S. Wacker, LLC sold the tower to Blackstone Group for $1.3 billion. The deal—as well as Blackstone’s subsequently announced $500 million renovation of the tower—excluded the Calder. This twist carries a fair bit of irony given the mega-collectors occupying positions of prominence at the firm: Blackstone’s chairman, CEO, and co-founder is Frick Collection trustee Stephen A. Schwarzman, while Metropolitan Museum trustee and private museum founder J. Tomilson Hill chairs Blackstone Alternative Asset Management.

With the litigation between Sears and 233 S. Wacker, LLC, still active, Universe was de-installed from the Willis Tower’s lobby and transported to storage in March 2017. Roughly 18 months later, in October 2018, Sears filed for bankruptcy, throwing the already-unsettled installation into an even greater arena of high-stakes legal strategy.

A former Sears store at the Rhode Island Mall in Warwick, Rhode Island. Image courtesy of Flickr.

Bankruptcy Blow by Blow

American bankruptcy law is a labyrinth winding enough to bring a Minotaur to tears. The most complex version of bankruptcy, Chapter 11, seeks to restructure the bankrupt company, its assets, and its debt so that the business can continue operating (and if all goes well, return to corporate health). The chosen strategy must be scrutinized by a committee of the bankrupt company’s largest creditors and approved by a bankruptcy court.

Sears filed for Chapter 11 last fall, but months of further turbulence set the company on the verge of liquidation at auction this week. However, as of early Wednesday morning, Sears’s billionaire chairman and former CEO, Eddie Lampert, appears to have been given one last attempt to bring the company out of bankruptcy hell, courtesy of a $5.3 billion bid for the estate and a plan to keep 400 stores running. The bankruptcy judge will decide whether or not to approve Lampert’s offer on February 1—hardly a given, since many creditors would reportedly still prefer liquidation.

People walk by a Sears store in Brooklyn in October 2018, after the colossal American retailer filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

Masters of the ‘Universe’

Although it may seem strange at first, Universe does not appear among the assets listed in the Sears bankruptcy docket. But this does not mean that the bankruptcy court is unaware of its value or uninterested in gaining control of the work. It may simply mean that its roughly $4 million price does not cross the threshold of disclosure within a bankruptcy estate that included more than $7 billion in assets last October. (Since the interest due on the piece has continued to accumulate over time, it has since surpassed the roughly $3.86 million price Sears intended to pay 233 S. Wacker in 2016.)

In fact, there are other indications that Sears is committed to pursuing the sculpture—and for good reason.

Had Sears viewed Universe as a low priority amid bankruptcy proceedings, it could have filed a motion to stay the litigation against 233 S. Wacker, LLC. Doing so would have meant that the lawsuit would effectively resume only once Sears emerged from bankruptcy, if it ever did so. But Sears has filed no such motion to date, which is doubly significant in the context of the brutal cost-benefit analysis that fuels bankruptcy proceedings.

Crucially, a bankrupt company must pay the attorneys and administrators working on its behalf using its own limited funds. As a result, the bankruptcy court will only sanction attorneys to pursue matters where the potential financial upside outweighs the estimated costs of litigating. In simpler terms: If it looks like it will cost more to sue than would be gained by winning the case, the bankruptcy court will simply let the matter drop.

All of which brings us back to 233 S. Wacker, LLC. When Sears filed for bankruptcy, anyone due anything from the retailer had the opportunity to file a claim with the bankruptcy court for what they believed they were owed. Doing so would guarantee only that the matter would be decided once and for all by the bankruptcy court—and nowhere else.

However, 233 S. Wacker chose not to file a claim as one of Sears’s creditors. Instead, it filed a notice of Sears’s bankruptcy with the Cook County circuit court, the venue for the still-active litigation between Sears and 233 S. Wacker, LLC over Universe. The question is: Why?

One theory is that 233 S. Wacker hoped that the circuit court would stay the Calder case until the resolution of Sears’s bankruptcy with the hopes of running out the clock on the retail giant, which “continues to burn through cash at a rapid rate,” according to the Wall Street Journal. If it just managed to maintain possession of the work until the bankruptcy bled Sears dry, 233 S. Wacker would win the Calder by default.

However, bankruptcy attorney Kristopher Aungst of Miami’s Wargo French called this possibility “an extremely high-risk play with a very high likelihood of a negative outcome.” In his view, it would be better for 233 S. Wacker to file a declaratory action lawsuit in this year’s bankruptcy asking the court to determine the ownership of the sculpture in its favor.

Nevertheless, according to a source with direct knowledge of the matter, Sears is still pursuing the 2016 lawsuit over Universe. In and of itself, this decision would confirm that Sears believes the work to be worth significantly more than the $3.625 million purchase price, the accrued interest, and the cost of litigating for the opportunity to pay both of those to 233 S. Wacker. The Cook County court docket shows that the lawsuit remains open, with a case status proceeding scheduled for February 4. Emails to a Sears spokesman and counsel for 233 S. Wacker went unreturned by publication time. Partners of 233 S. Wacker could not be reached for comment.

Alexander Calder paints the fuselage of a Boeing 727-291 passenger plane as a commission from Braniff International Airways, Dallas, Texas, 1975. Photo by Camerique/Getty Images.

A Vision for the Future

Amidst protracted legal wrangling like this, it can be easy to lose touch with a contested artwork’s soul, as well as the intentions of its creator. According to a source with direct knowledge of the matter, Universe has remained in storage since its March 2017 de-installation, meaning that one of Calder’s masterworks has not seen the light of day for nearly two years.

No matter which party prevails in the lawsuit, though, the fate of Universe will depend in part on the Calder Foundation. Alexander Rower, the foundation’s president and the artist’s grandson, told artnet News that it is “an open question as to what could be the next steps for the sculpture” after a potential sale.

“It’s already left the Sears Tower, where it was commissioned as a site-specific work,” he says. “By US law, it can’t be re-installed in another place without our involvement.”

Yet Rower says the foundation remains open-minded about returning Universe to view. “Whoever buys it would need to come to the foundation and get our assistance in creating a new space that would be suitable for the artist’s vision,” he said. “I would never say it could never be [installed] in another place. That’s not the right point of view.” He says that various parties with an interest in the work have been in touch with the foundation during the long ownership battle, and those conversations have given him confidence that a mutually agreeable solution can be reached once the litigation is resolved.

Nor does Rower take a hard stance about the prospect of the work leaving Chicago. His hopes for the work’s second life have more to do with the viewing environment than geography. In his mind, it would be better for Universe to make its way to a museum than another office building. Ironically, even the chaos of the Sears bankruptcy could benefit the art world in the end. “Action [in the courts] would be good for us, because whatever can get Universe back on display in a public context is best,” Rower says. “We would hate to see it locked up somewhere for the next 20 years.”