“I wanted it to be a rich literary experience, so I tried to use words and ideas that children might not otherwise experience. People aren’t as critical of New Media as they are of cinema or traditional storytelling, but I think more should be expected of it.”

These are Theresa Duncan’s words from an interview prior to her death. They were delivered by her friend Lia Gangitano to a full house at Rhizome, where on April 16 presentations and a panel discussion about Duncan’s work took place. Featuring Gangitano, video game critic Jenn Frank, FEMICOM Museum founder Rachel Simone Weil, and Rhizome digital conservator Dragan Espenschied, the event celebrated Duncan’s pioneering oeuvre of CD-ROMs created between 1995–1997, which thanks to a Kickstarter campaign by Rhizome, now available for play by a whole new generation of kids—and adults—on Rhizome’s website.

Lauded as a refreshing and much-needed departure from the mid-90s girl-gaming culture that revolved around branded, acceptably feminine products like “Barbie Fashion Designer” and “Mary-Kate and Ashley’s Crush Course,” Duncan’s games “Chop Suey,” “Smarty,” and “Zero Zero” showed girls that they could be pretty and smart—and also weird, adventurous, and even a little naughty sometimes.

“The sum of young girls true interests were not being represented [at the time],” noted Frank.

But what makes Duncan’s works truly special is that while they were created for young girls, they are equally appealing to both young boys and adults. More than just interactive games, they function as “labyrinthine art installation[s] for the player to walk through,” Frank explained.

Part of this is due to Duncan’s prose, which are vivid, poetic and equal measures humorous and melancholy. Duncan has the ability to construct a layered world that feels both familiar and surreal at the same time—the games are made for children, but they also mimic the feeling of what it’s like to be a child.

It’s impossible to fully appreciate the works today without at least a cursory understanding of Duncan’s life. A video game designer, blogger, critic and filmmaker featured in the 2000 Whitney Biennial, Duncan tragically committed suicide in 2007. A week later, her partner, visual artist Jeremy Blake, committed suicide by walking into the Atlantic Ocean near Rockaway Beach. Dubbed “the Golden Suicides,” by Nancy Jo Sales in her story for Vanity Fair, the glamorous couple became a focal point for the media. It is widely rumored that prior to their deaths, the couple was being followed and harassed by members of the Church of Scientology.

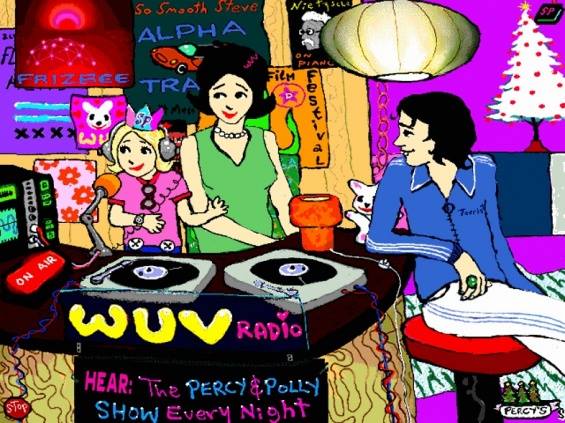

A still from “Chop Suey.”

Photo: via Tumblr/Womanhouse.

Blake created illustrations and provided art direction for “Smarty” and “Zero Zero,” while Duncan’s Magnet Interactive co-worker Monica Gesue co-created “Chop Suey.” Rhizome’s Michael Connor describes the works as “both deeply personal and highly collaborative. They are singular artworks but also anthologies of other things.”

The works contain a surprising variety of references, including philosophy, the history of fashion and perfume, and the works of Walter Benjamin and Buckminister Fuller, most of which were personal interests of Duncan’s.

Duncan once described “Zero Zero” as “Twin Peaks for kids,” and fantasized about David Lynch turning the game, which is set in France on New Year’s Eve at the turn of the century, into a film. She also talked about creating a game called “Apocalypstick” in which the heroine uses weapons disguised inside makeup compacts.

“These three games have been a trilogy,” said a former co-worker of Duncan’s, who was sitting in the audience at Rhizome. “Particularly as a personal statement of who Theresa was, if you look at Chop Suey‘s position as the innocent child, all the way progressing up to this child at the turn of the century…[and] they were done in three year’s time. It’s a lot of energy. The collaboration between [Duncan and Blake] was just over the top. I can’t tell you. And they thought each other’s thoughts were just…magnificent.”

“To me,” he added, “it can’t be…it’s not just ‘girls’ software.'”

The Theresa Duncan restoration is just the first in a series of projects Rhizome will enact using a new technology called cloud-based emulation, which makes interactive CD-ROMs usable through any modern web browser. For more information, visit Rhizome.