Carlos Rosales-Silva’s first solo show in New York City, “Sunland Park,” is a collection of paintings on custom shaped wood panels inlaid with plastics, paint-sand mixtures, and dyed stones. These charged works blend geometric abstraction and Tex-Mex architectural flair, channelling this artist’s impressions of the bordertown neighborhood in El Paso, Texas where he grew up absorbing the psychedelic skies.

These works are saturated with rich, brilliant hues of the murals, hand-painted business signs, and mountainous landscapes of the Chihuahuan desert. The body of work at Ruiz-Healy Art is also self-consciously an ode to the home Rosales-Silva shares with the Tiwa, Manso, and Piro peoples and an acknowledgement of American modernism’s indebtedness to Indigenous art forms.

“All this stuff existed here in North America before colonization and it had this perilous journey where it was ripped off, recreated without citation, and filtered into these new forms that were revolutionary,” Rosales-Silva told me. “There’s never been an honest art history.”

Installation view of Carlos Rosales-Silva’s “Sunland Park” at Ruiz-Healy Art. (Photo courtesy Ruiz-Healy Art.)

Though it is well-documented that early North and South American modernists were influenced by Indigenous designs, rituals, and philosophies, art historical writing has a notable insistence on citing European antecedents over all else for modernist movements in the Americas. Navajo sand paintings, Pueblo dance ceremonies, and techniques of collapsed space on tapestries, paintings, and sculptures were avowedly among the inspirations for many of the most famous US Abstract Expressionist painters, including Rothko, Pollock, and Newman. Besides being dishonest, the persistent Eurocentrism in American art history is boring and has stifled nuanced readings of modern art in America.

Like many of his pieces, Rosales-Silva’s Biblioteca (2020) uses a mixture of paint and sand to create a textured surface like stucco, a popular material in the southwest U.S. for coating building exteriors. The overwhelmingly saturated colors create vibrational effects that nod to a color language associated generally with Latino culture and more specifically with Mexican architecture.

Carlos Rosales-Silva, Biblioteca (2020). (Photo courtesy Ruiz-Healy Art.)

The title and subject of Biblioteca (2020) may refer to the San Antonio Central Library that was built by the Mexican architect Ricardo Legorreta. He and his peers Pedro Ramírez Vásquez and Teodoro González de León insisted they were borrowing from Indigenous forms of Mexico—even as critics have tended to overstate Le Corbusier as their fundamental inspiration.

The idea of multiplicity within identity and influence is essential to understanding the contexts in which Mexican-American, Chicanx, or brown artists live and work (Rosales-Silva identifies as all three). In his works at Ruiz-Healy, you see this in the way that Rosales-Silva pushes his forms beyond traditional renditions while using unconventional materials and layering his references.

Diablo en el Jardín (2020), for example, is a devilish red blob, graphic and fluid in shape like a musical note or calligraphic character. It contains a wavy piece of shiny acrylic plastic ending in a droplet. On its bottom right leg forms a circular pool of crushed stone applied with teal, baby pink, grass green, and yellow.

Carlos Rosales-Silva, Diablo en el Jardin (2019). (Photo courtesy Ruiz-Healy Art.)

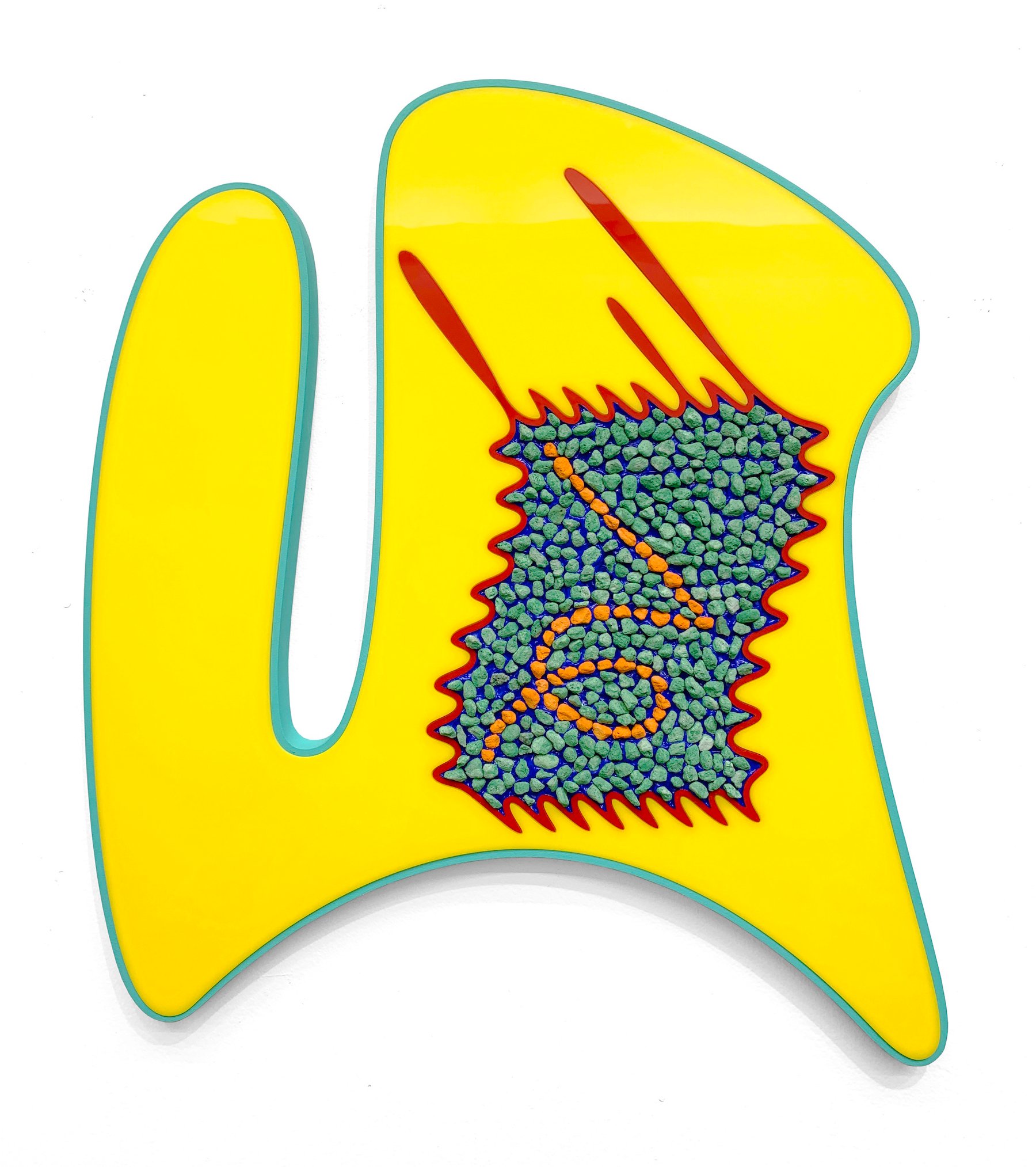

Another piece, La Pulga (2019), is shaped like a vague thumbs up, framed by a thin border of turquoise inlaid with a yellow acrylic plastic, like the shiny laminate of inexpensive furniture. From the center, red droplets seem to ricochet from a skewed bed of turquoise rocks. There’s an animated and even amusing character to the expressive shape of the panels combined with the energy from their color and competing textures.

Carlos Rosales-Silva’s “Border Exchange Studies,” as seen in “Sunland Park” at Ruiz-Healy Art. (Photo courtesy Ruiz-Healy Art.)

For Rosales-Silva, abstraction didn’t always seem like a relevant way to make work considering how important history was to his practice. The works of Black abstractionists showed him that there can be a poetic way to blend the personal and political into the abstract. As inspirations, he lists artists such as Howardena Pindell, Stanley Whitney, and Jack Whitten. (In his recently released journals, Whitten began a list of painting objectives with, “Remove the European significance of touch in painting.”)

Rosales-Silva is considered a first-generation American because during the Great Depression, his grandfather was repatriated to Mexico despite being born in South Texas. The sensibility that comes from inheriting these troubled histories are what he alludes to when he speaks of the “tense state of brownness” as a force in his work: cultural assimilation as a means of survival, a complicated relationship with indigeneity, and the sense of being a brown person in an art world where there aren’t many.

Carlos Rosales-Silva, Nopalitos, Tuna, y Xoconostle (2020). (Photo courtesy Ruiz-Healy Art.)

Yet Rosales-Silva has found his way through an abstract art form that infuses a cultural perspective while making a space for critical conversations about history. Nopalitos Tuna, y Xoconostle (2020) is the artist’s painting of cactus fruits, rendered on a circular panel. “You are not a Xicano artist, if you don’t have a nopal painting,” I teased him.

“I’d feel like I was dishonoring my culture without one,” he replied, laughing.

Rosales-Silva and I have an ongoing discussion about “nopal art”: the over-reliance on cultural symbols like nopales, plátanos, or Virgen de Guadalupes that make a piece legibly “Latinx.” Such overt symbols often overpower any criticality in the work, making it fall prey to stereotypical, celebratory clichés that institutions often use as a stand-in for “Latinx art.”

Installation view of Carlos Rosales-Silva’s “Sunland Park” at Ruiz-Healy Art. (Photo courtesy Ruiz-Healy Art.)

But although this particular piece is indeed an image of a cactus with a title combining Spanish and Nahuatl words, it’s also an abstraction. Though the fear of losing ownership over cultural symbols is not imagined, there are many manners in which brownness can exist. Rosales-Silva chooses instead to provoke uncertainty, disassemble and reorganize the visible, and through that process he captures a much-sought-after magic.

“Carlos Rosales-Silva: Sunland Park” is on view at Ruiz-Healy Art, New York, through March 27, 2021.