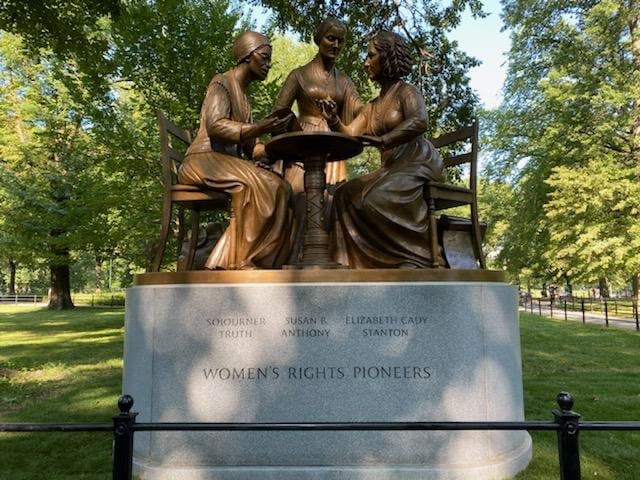

Winning the right to vote for women took 70 years, and many pioneering suffragists—including Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Sojourner Truth—never lived to see the certification of the 19th amendment on August 26, 1920. Today, exactly 100 years later, on what is now celebrated as Women’s Equality Day, those three women have been honored in a monument in Central Park.

On hand in the park to celebrate the occasion was former presidential candidate Hillary Clinton.

“There is nothing more important to honor the women portrayed in this statue than to vote,” she told the small, socially distanced crowd. “While the passage of the the 19th amendment was a critical, important, historic victory, it was also an incomplete one. It would take decades longer to guarantee the franchise to women of color, especially Black and Native American women, and a century later, the struggle to enforce the right to vote continues.”

The 14-foot-tall Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument, by sculptor Meredith Bergmann, literally places women’s history on a pedestal and honors the role of three New Yorkers in that monumental effort. “Our rights were not gained by one dramatic action but from long shared struggle,” Bergmann said after the unveiling.

Hillary Clinton poses with sculptor Meredith Bergmann after the unveiling of the statue of women’s rights pioneers Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Sojourner Truth in Central Park. Photo by Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images.

The monument is the first public monument to honor real historical female figures—rather than fictional ones—in Central Park, where it joins statues of Alice in Wonderland and Mother Goose. It is also the first depiction of an African American there. In the city as a whole, there are just five existing civic sculptures of historic women, compared to 145 of men.

“I can’t think of a better monument to the history and spirit of New York than these fiercely determined women who fought for a better, more inclusive, more just future,” said New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand in a message broadcast during the unveiling ceremony, which was livestreamed from the park. “Every woman who votes, protests, or serves in office today does so standing on the shoulders of these three giants.”

The nonprofit Monumental Women spearheaded the new statue, raising $1.5 million in funds—including contributions from local Girl Scout troops from their cookie sales—to donate the work to the city. The effort was seven years in the making.

“Seven years ago, no one was talking about statues—and now folks are mostly talking about tearing them down,” said Manhattan borough president Gale Brewer, who, with councilwoman Helen Rosenthal, raised $135,000 for the project. “We set out to break the bronze ceiling, and it wasn’t easy.”

Meredith Bergmann, Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument (model). Photo by Michael Bergmann.

There hadn’t been a new permanent sculpture in the park in 70 years, and Monumental Women received all sorts of reasons why that wasn’t going to change, Brewer recalled. “The park is closed to new statues. Women don’t want a statue, they want a garden. If we say yes to this statue, we have to say yes to any statue. And, my personal favorite, you have to prove that each of these women actually set foot in Central Park.”

Now, the monument, located on the park’s Literary Walk near 68th Street, is the first in a new wave of public artworks honoring New York’s historic women. The city introduced the She Built NYC initiative to commission artworks honoring women’s history in 2018, and has since announced plans for monuments to jazz legend Billie Holiday, public health pioneer Helen Rodríguez Trías, civil rights leader Elizabeth Jennings Graham, lighthouse keeper Katherine Walker, and Shirley Chisholm, the nation’s first Black congresswoman.

Central Park is also getting a new statue of Albro Lyons, Mary Joseph Lyons, and their daughter Maritcha Lyons, educators and abolitionists who lived in Seneca Village, the African American community displaced to make way for the park.

Meredith Bergmann working on the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument. Photo by Michael Bergmann.

These efforts to increase representation of women in the city’s public places are not without controversy. The public was invited to nominate women for She Built NYC, but the top vote-getter, St. Frances Xavier Cabrini, was ultimately passed over, outraging some among the Italian American community. And the Lyons family sculpture has been criticized for its planned location, some 20 blocks north of the former village.

The Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument, too, faced significant backlash for its original intent to depict just Anthony and Stanton. After widespread criticism that the design ignored the contributions of Black women to the suffrage movement, the artist added Truth to the monument in 2019. Nonetheless, it still has its detractors, even after a second second redesign addressed concerns that Truth seemed too passive in the sculpture.

In pre-recorded remarks aired at the unveiling, New York congresswoman Carolyn Maloney called on viewers to draw momentum from the new monument and join her decades-long push to build a Smithsonian Women’s History Museum on the National Mall, and to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, currently caught in a legal battle.

“For too long women’s history has been swept aside or simply ignored,” Maloney said. “No more.”