A long-lost relic of Jewish folk art has been revealed after being hidden—but not forgotten—behind a wall for more than 30 years.

“The Lost Mural” is an interior apse painting created in 1910 by Ben Zion Black, a 24-year-old Lithuananian playwright, poet, and sign painter, for the former Chai Adam synagogue in Burlington, Vermont. Aaron Goldberg, a descendant of Burlington’s earliest Jewish residents, founded the Lost Mural Project to recover Black’s work,

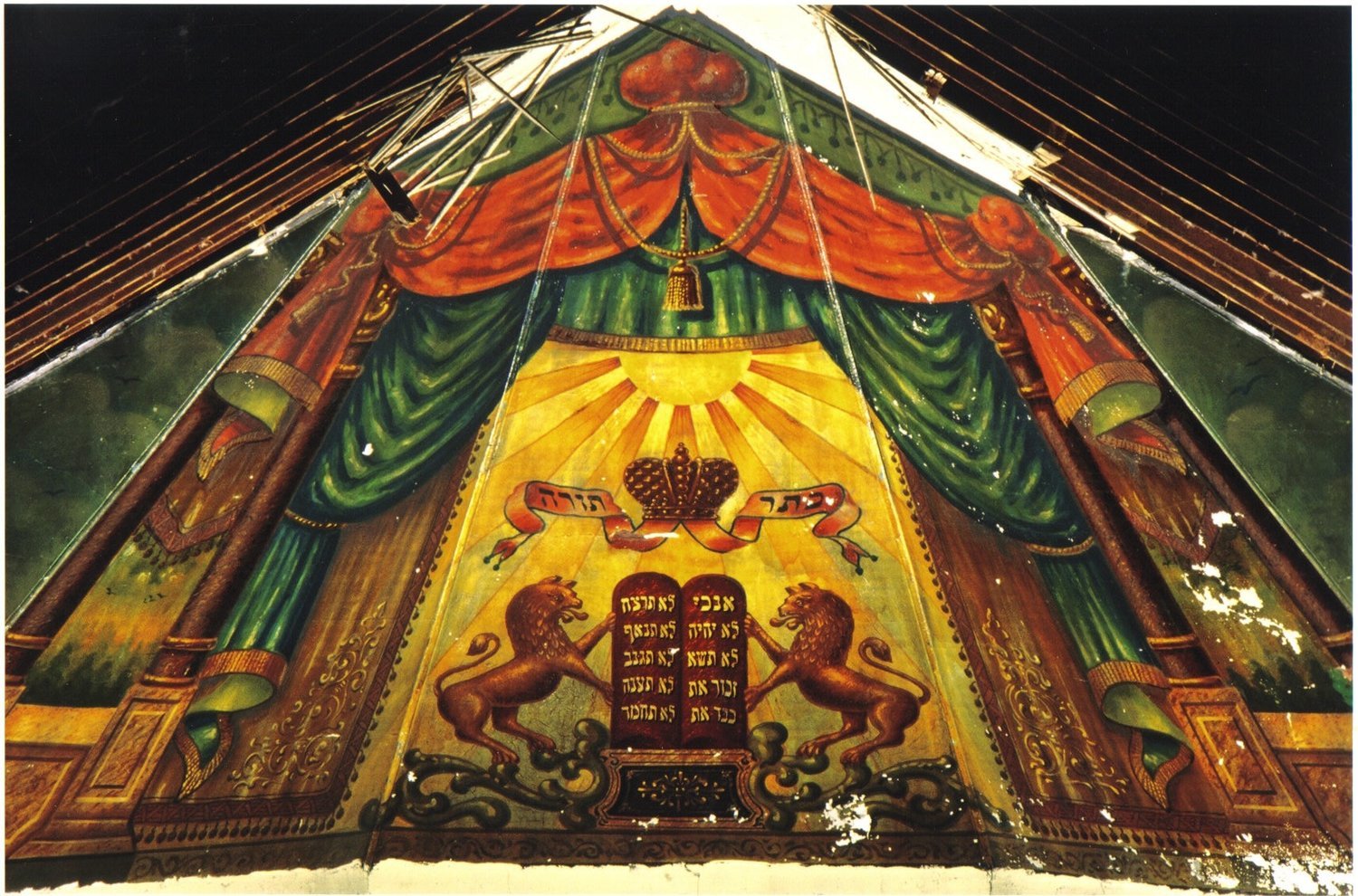

According to the project’s website, Black’s 155-square-foot triptych “is part of a long tradition of synagogue wall painting that was particularly advanced in Eastern Europe between the early 18th- and mid-20th centuries.” Most artworks in this genre were set ablaze during the Holocaust, remembered now only through old photos and watercolor renditions.

The mural after full restoration, June 2022. Photo by Eric Bessette. All images courtesy of the Lost Mural Project.

“There is nothing like this elsewhere in this country,” Josh Perelman of the Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia told the AP, calling Black’s mural “both a treasure and also a significant work, both in American Jewish religious life and the world of art in this country.”

The project’s site says itinerant peddlers from Čekiškė, Lithuania, built the Ohavi Zedek synagogue in 1887. Two years later, Burlington’s Jewish community had grown to 150 residents, so they broke ground that year on Chai Adam. The classic wooden synagogue became their second house of worship, just 500 feet from the city’s first.

Black arrived in Burlington in 1910 and built a reputation as a gifted painter, mandolin orchestra leader, and champion of Yiddish culture. In 1910, Chai Adam offered Black $200, or about $5,314 by today’s standards, to paint the mural and the synagogue’s ceilings.

Ben Zion Black, 1910. Photo by Myron Samuelson.

He depicted the Tent of the Tabernacles according to the Book of Numbers, “including the Decalogue flanked by rampant lions and surmounted by a floating crown, all bathed with the rays of the sun, and framed by architectural elements and elaborate curtains.” Though the work’s rich colors and symbolism struck aesthetic chords, congregants bristled at the artist’s idolatry of angels and inclusion of musical instruments, which are banned on the Sabbath.

Chai Adam didn’t call on Black again. The synagogue closed in 1939 and merged with the congregation of Ohavi Zedek.

The building was sold in 1986 and turned into apartments, but the owners agreed to seal Black’s artwork behind a wall in hopes that advocates would one day return to its rescue. Then it spent 25 years in hiding.

In 2012, Burlington’s Jewish community partnered with the building’s new owner—Offenharz, Inc—to remove the false wall and assess the Lost Mural’s condition. Insulation, carelessly installed, had done its damage. They found flaking plaster, coats of shellac, and natural debris that obscured the mural’s true, vivid palette.

Raising more than $1 million from hundreds of donations, the project extricated the artwork by crane in 2015 and transported it by truck to its current home in the lobby at Ohavi Zedek. Cleaning started last year and professionals from the Williamstown Art Conservation Center have since restored the mural’s hues based on 1986 archival slides, sealing their work with a new glaze.

The mural during the restoration process in 2021. Photo by Eric Bessette.

Ohavi Zedek’s senior rabbi, Amy Small, saw it all, calling the tale “both a Jewish story and an American story,” as well as a “universal story,” in the AP.

Burlington Free Press said the unveiling ceremony on June 28 was attended by officials including former Vermont governor Madeleine Kunin, U.S. Representative Peter Welch, and Vermont Arts Council executive director Karen Mittelman. Later that evening the public joined for a party replete with Yiddish music and dance by the Nisht Geferlach Klezmer Band.

The Lost Mural Project isn’t over. The secular nonprofit is seeking donations “to replicate green corridors on the original painting that did not survive,” Goldberg told AP. In the meantime, you can catch a tour of this global relic on your next trip to the Queen City.