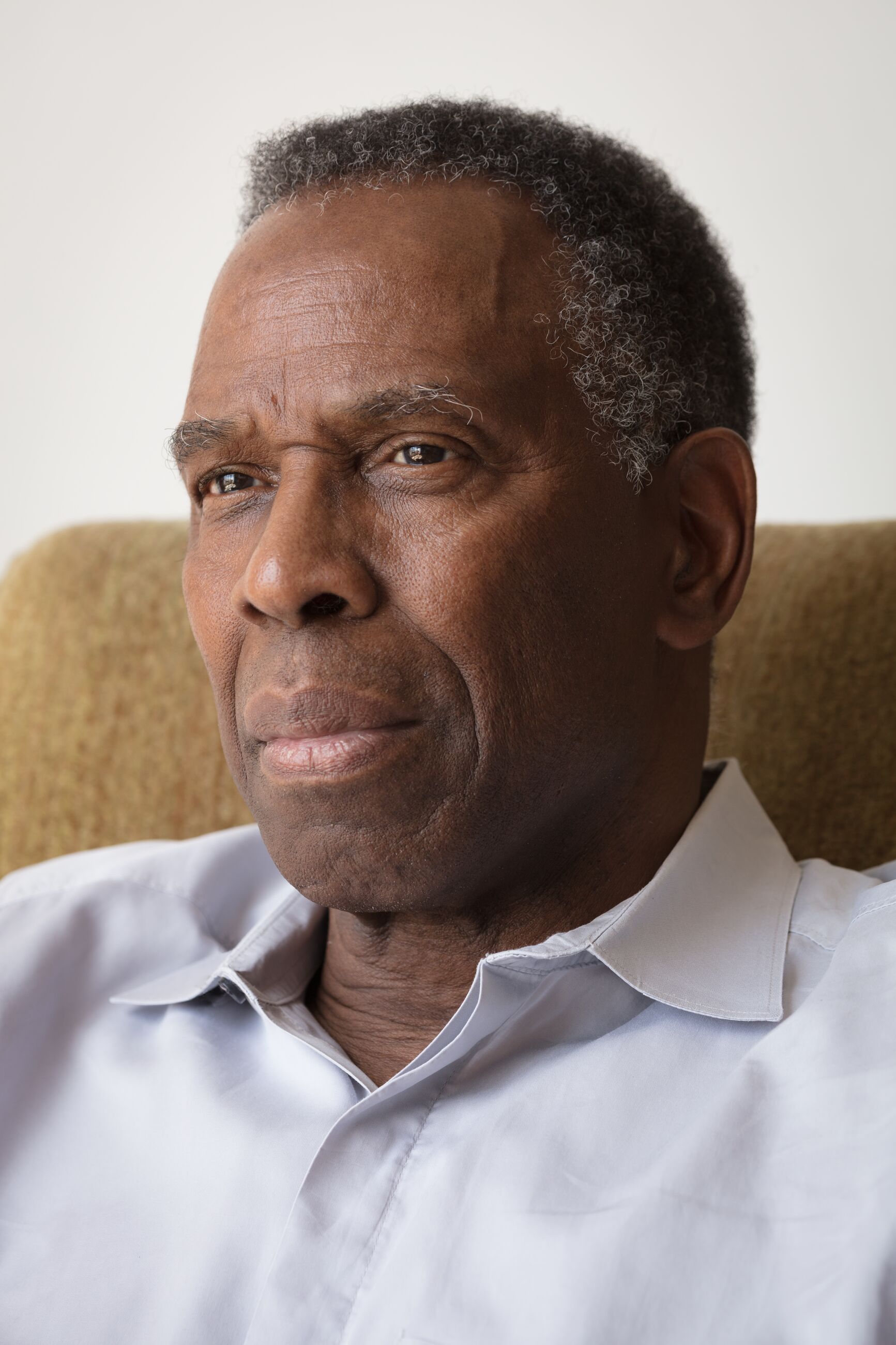

During his new lecture series at Hauser & Wirth in Los Angeles, the artist Charles Gaines encourages class participation, especially as he broaches denser topics.

“What I expect to happen is that I will say things or articulate ideas and nobody will understand,” he tells his classroom of 26 students, at which point they should “just interrupt and say, ‘Can you explain that?’”

The 10-week lecture program coincides with “Palm Trees and Other Works” (through January 5), Gaines’s first exhibition at Hauser & Wirth. (He joined the gallery late last year at the age of 74.) Since 1989, he has been an influential force in the Los Angeles art scene as a professor at CalArts. His list of prominent former students includes Mark Bradford, Henry Taylor, Lauren Halsey, and many others, who fondly recall his mentorship and theoretical rigor—as well as their confusion.

Bradford, reminiscing about his time at CalArts during the Institute of Contemporary Art gala last year, said, “[Taylor] and I would have conversations about Charles Gaines, like, ‘god damn, did you understand what he said?’”

Titled “Library of Ideas: A Course by Charles Gaines,” the classes on aesthetic and critical theory are free and open to the public (a steal, considering CalArts’s $50,850 annual tuition). The idea was Gaines’s, inspired by “a certain nostalgia I had for when artists were pretty well read,” he says. As far as “philosophy and critical thinking,” he adds, artists today are lacking “big time.”

Installation view, “Charles Gaines: Palm Trees and Other Works” at Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles, 2019. © Charles Gaines. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

Gaines is known for the conceptual practice that he developed in the 1970s, when he wanted to diverge from what he describes as a “Eurocentric model” of creating art.

“The whole idea that a work of art is based on the creative imagination and expressivity, to create something from nothing—that didn’t work for me,” he says. “What I started to do was to develop a system, like an algorithm, that set the terms for the production of images.” (Given the geometry involved in his work, Gaines delights in telling people that he has “absolutely no interest in math.”)

His earliest works took photographs of walnut trees and remapped their silhouettes onto numbered grids, effectively pixelating them. At Hauser & Wirth, he’s applied this treatment to the desert landscape of Joshua Tree, overlaying tall, black-and-white photographs of palm trees with multiple sheets of gridded plexiglass.

Each sheet is painted with the manually pixelated ghost of a different tree in a different color—red, cerulean, neon green. Stacked on top of one another, they amount to a single, dynamic, full-bodied tree deeper than the sum of its parts.

Gaines was born in 1944 in Charleston, South Carolina, and at age five, moved to Newark with his parents during the Great Migration. He speaks frankly about the oppression of living under Jim Crow. “At the time, I was convinced the best thing to be in America was white,” he says.

He has written and curated exhibitions on the topic of the art world’s marginalization of black artists, notably in his 1993 group show, “The Theater of Refusal: Black Art and Mainstream Criticism” which featured David Hammons, Adrian Piper, and other then-emerging black artists. His current Hauser & Wirth exhibition is scored with the somber piano riffs of his 2018 work Manifestos 3, a musical transliteration of texts by Martin Luther King, Jr., and James Baldwin.

Charles Gaines, Numbers and Trees: Palm Canyon, Palm Trees Series 2, Tree #4, Kumeyaay (2019). © Charles Gaines. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

The absence of black figures in Gaines’ work, however, was a marginalizing factor in his early career. “I would be making so-called ‘white art’ because I wasn’t making certain images people thought I should be making,” Gaines recalls. “This presupposition about how to show the black experience in your art was formulaic and didn’t make sense to me.”

“For an artist of color working in the ’70s, post-Conceptualism was a pretty lonely place,” says artist and former Gaines student Edgar Arceneaux. The ’90s didn’t show much progress. At the Art Center College of Design in 1995, when Gaines was a visiting professor and Arceneaux was a student, Gaines was the first Conceptual artist of color Arceneaux ever met.

“I found a real kinship with him,” Arceneaux says. “I was one of those artists who didn’t fit into the identity politics track that the professors were trying to push me into, and he was the person who helped give me the language and concepts to [express] my own thinking.”

Despite the different practices Gaines’s former students have pursued, they’ve expressed a similarly profound sense of gratitude for the wisdom he’s imparted. Artist Andrea Bowers, who was a student of Gaines’s in 1990, credits her own political engagement to his activist discourse. “Had it not been for Charles, his questioning of notions of genius, of who has privilege and who doesn’t, I don’t think I could make the work that I make.”

“He’s been the best of the best mentor,” Halsey says. “He’s the first person I ever asked, ‘How do you make an invoice?’” Yet the conceptual tenets of his practice remain a mystery. “Charles, one of these days,” she says, “I’m going to get the courage to ask you—what are the systems?”

“It’s not that hard to understand,” says Gaines, taking a moment to show his gridded notations of a walnut tree. At Hauser & Wirth, his lesson plans will span aesthetic theory from Classical to Modern times, from Plato through Immanuel Kant and onto Rosalind Krauss.

Nothing to be afraid of, according to Arceneaux. “Even if you don’t get all the details, you can still follow along.”