The extensive archives of Charles White have been digitized by the Smithsonian—and now they’re all freely accessible online.

Long neglected, the important social realist artist’s stunning figurative works celebrating Black life have recently experienced a renaissance of interest, with a critically acclaimed touring show traveling to MoMA, LACMA, and the Art Institute of Chicago in 2018 and 2019.

Some 17,000 photographs, letters, scrapbooks, newspaper clippings, and other objects from 1933 to 1987—a span of time that takes us from White’s teen years through and past his death in 1979—are included in the archive. They were digitized over the course of 2020 by a two-person team at Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

The digitized documents offer a surprisingly deep look into the artist and activist’s life. His high school report cards, for instance, give us a sense of what he was like as a student. English, Civics, and Algebra were a struggle; US History and Illustration a strength. He got the equivalent of a “D” in art history during his senior year.

A wedding announcement, meanwhile, gives us a glimpse into his marriage with his second wife, Frances Barrett. “Charles designed our wedding announcement and our wedding ring,” wrote Barrett in a personal note. “The ring symbolized the two individuals, Charlie and Fray, coming together, as one, but secure in our paths we would share.” On the front of the announcement, the ring encircles the initials of the soon-to-be husband and wife.

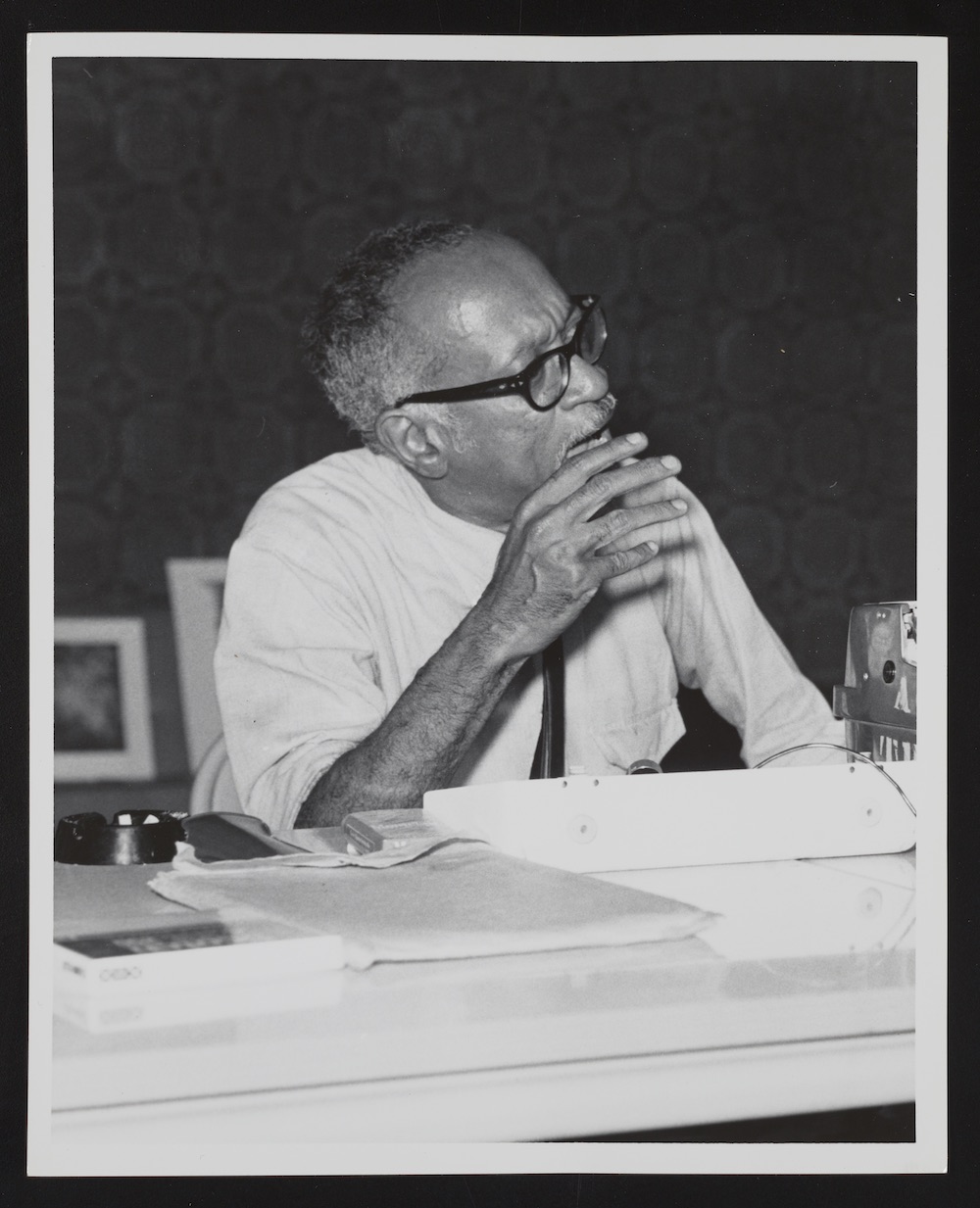

Charles W. White, “Address to the Second Annual Conference of Negro Artists,” 1960. Charles W. Whitepapers, 1933–1987. Courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

The process of digitizing White’s papers took some six months, said Rayna Andrews, one of the two Smithsonian archivists to work on the project, in an email to Artnet News. “I don’t know that my impression of him changed, so much as it became more nuanced,” she explained.

Listing some of her favorite inclusions in the archive, Andrews points to the “Address to the Second Annual Conference of Negro Artists” that White delivered in 1960. “It raises concerns about the treatment of Black people in the art world. It’s striking how concerns related to representation still resonate today,” the archivist said. “In the address, White asks, ‘Where are the Negro Museum Curators, Directors or Board members?…How many Negro Art Directors, set designers, or skilled artists are there employed in the film industry, theatre or T.V.?”

Letter from Alice Walker Leventhal to Charles W. White, April 1971. Charles W. White papers, 1933–1987. Courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Stephanie Ashley, the other Smithsonian archivist behind the digitization effort, circles back to a lovely letter from author Alice Walker in the early 1970s.

Walker, just 27 at the time, asks White where she might purchase one of his works: “…the main work by you….that I’d like to buy is a drawing I saw one time in the New York Times Book Review. It was of a man sowing seed. It moved me deeply, for I am from Georgia (Eatonton) and my father was for many years a sharecropper and I remember seeing him sowing seeds just that way…. it is a beautiful thing you’ve done.” (The note closes with a postscript suggesting that, should White locate a copy of The Best Short Stories edited by Langston Hughes, he might read To Hell With Dying, the author’s first published story.

Holiday card from Charles White and family, circa 1974. Photographer unknown. Charles W. Whitepapers, 1933–1987. Courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Walker’s is just one of many poignant being of correspondence in the archive, which also includes letters to and from people like Paul Robeson, Rockwell Kent, and David Driskell.

“We artists have two great enemies: poverty and envy,” fellow artist Romare Bearden wrote to White in a 1971 missive. “Sometimes we can do something about the first Rider of the Apocalypse; but envy increases as your ability, or I should say, the artist’s ability increases—we must live with it.” It’s unclear to what Bearden is referring.

You can explore those letters and the rest of White’s papers here.