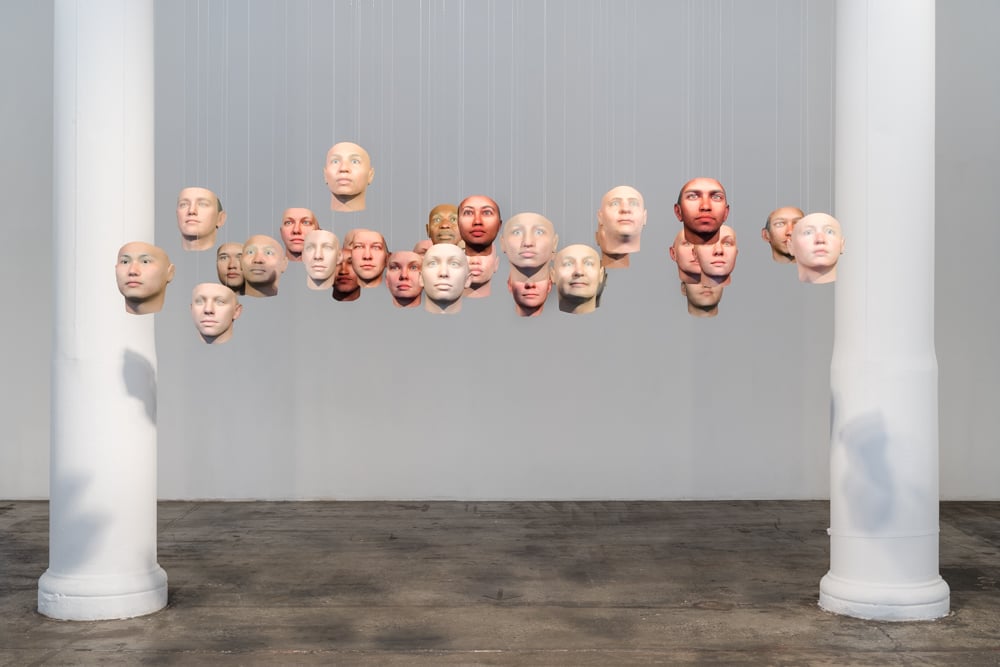

An unsettling sight greets visitors at New York’s Fridman Gallery: a crowd of life-size 3-D faces hangs from the ceiling. These mask-like portraits in full color have been algorithmically generated from an analysis of DNA samplings belonging to Chelsea Manning, the US Army intelligence analyst-turned-whistleblower who went to prison for sharing classified information about American military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The 3-D prints, collectively titled Probably Chelsea, are the work of artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg, and serve as the centerpiece of her current exhibition, “A Becoming Resemblance,” curated by Roddy Schrock. None of them look particularly like Manning, a transgender woman formally known as Bradley Manning. Some of the faces appear to be of African or Asian descent, even though Manning herself is white and of Northern European ancestry.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg and Chelsea Manning, Probably Chelsea (2017). Courtesy the artists and Fridman Gallery, New York.

That is because reading DNA is a highly subjective science. The gene commonly associated with blue eyes and Northern Europe, for instance, also appears in the DNA of Hispanic, African-American, and South Asian populations, as the press release explains.

“This piece is about pushing away genetic determinism,” Dewey-Hagborg told artnet News. “Ethnicity is not something that you can tell just by looking at a person’s DNA. You can make probabilistic guesses about what their ancestry might be.”

She is concerned, she explained, about the increasing use of so-called DNA mugshots by law enforcement, a new form of policing that creates crude facial models of suspected criminals from leftover DNA samples.

“The way that these portraits are presented to the police make it look as if there is one conclusive face that represents a determined face based on the data, rather than the real plurality of possible faces that could be produced.”

Heather Dewey-Hagborg and Chelsea Manning, Probably Chelsea (2017). Courtesy the artists and Fridman Gallery, New York.

By contrast, the wide variety of portraits generated for Probably Chelsea “show how limited these efforts are,” said Dewey-Hagborg. The 30 faces underscore the universality of the human condition and only begin to hint at “all of the different stories that your DNA data can say about you.”

She’s been interested in those stories for several years now, having made the same type of portraits of strangers for her 2012 project Stranger Visions. The artist used strands of hair, chewing gum, cigarette butts, and other DNA traces picked up from the street to create her faces.

In 2015, when Manning was still in jail, PAPER magazine interviewed her but was prohibited from photographing her. Dewey-Hagborg’s work offered a unique solution. Manning put a few cheek swabs and strands of hair in the mail and sent them to Dewey-Hagborg. The artist, enthusiastic about the project, went to work.

“She’s someone I really admire,” said Dewey-Hagborg. “It took so much courage to do what she did and risk everything to make injustices public and put the truth out there.”

Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s initial forensic DNA phenotype of Chelsea Manning, made leaving out the sex parameter, for PAPER magazine. Courtesy of the artist.

The PAPER profile used two possible Manning portraits, one of which was female, the other more androgynous. Manning, who had been incarcerated since her arrest in 2010, had not been photographed since her 2013 conviction—and the subsequent announcement that she would undergo hormone therapy to transition from male to female. As such, the portrait was deeply meaningful, restoring her visibility despite her 35-year sentence, without tying her to a masculine appearance at odds with her self-proclaimed feminine identity.

“Our society’s dependence on imagery says a lot about our values. Unfortunately, prisons try very hard to make us inhuman and unreal by denying our image, and thus our existence, to the rest of the world,” said Manning in a statement. “A DNA portrait could give me back some of the visibility that I have been stripped of for years.”

Heather Dewey-Hagborg,

Radical Love, Chelsea Manning (2016). Installation at World Economic Forum in Davos. Courtesy the artists and Fridman Gallery, New York.

Today, in the wake of President Donald Trump’s recent announcement, via Twitter, that he would no longer allow transgender persons in the military, the work has added resonance. If Dewey-Hagborg can read Manning’s DNA and derive both male and female portraits, it speaks powerfully to the mutability of human sexuality. It’s an idea that is especially powerful given the recent rise in gender fluidity.

Manning spoke out against the proposed ban in a New York Times opinion piece, saying “This is about systemic discrimination. Like the integration of people of color and women in the past, this was a sign of progress that threatens the social order, and the president is reacting against that progress.”

“Chelsea worked so hard when she was in prison for transgender rights…. I think the impact of that fight will outweigh these really short-sighted comments that Trump throws out there without even thinking,” Dewey-Hagborg said. “I’m hopeful that we will end up having more rights rather than less.”

Chelsea Manning in May, after her release from prison. Photo via Instagram.

Manning’s belief in governmental transparency makes her a particularly fitting subject for Dewey-Hagborg. Stranger Visions definitely scared people, and it was meant to do so. “That this amateur could wander around the city, picking up your genome and then analyzing it in a community lab…” she trailed off. “The point was to look at surveillance risks that were emerging that no one was talking about.”

Manning, who declined interview requests for this story, stopped by the exhibition opening on August 2, fulfilling something of a prophecy. Manning and Dewey-Hagborg stayed in touch after the initial portrait project to work together with illustrator Shoili Kanungo on a graphic short story called Suppressed Images. The comic book envisions a future where then-President Barrack Obama commutes Manning’s sentence, and she is then able to see the exhibition of her DNA portraits.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg and Chelsea Manning, Suppressed Images (2016), illustrated by Shoili Kanungo. Courtesy the artists and Fridman Gallery, New York.

Fortuitously, on the day of the comic’s release, President Barack Obama did commute Manning’s prison sentence, and she was finally released on May 17, 2017. One of the drawings from the comic is on view in this current exhibition.

Despite the looming setback in transgender rights threatened by Trump, Manning sees “A Becoming Resemblance” as proof of how far society has come in its understanding of gender.

“It’s an incredible leap for humanity to start to break down the automatic factionalism that gender, race, sexuality, and culture have been the basis of,” Manning said, noting that there’s no “one-size-fits-all category” for human identities.

As Dewey-Hagborg put it, “on a molecular level, we are all Chelsea Manning.”

“Heather Dewey-Hagborg & Chelsea Manning: A Becoming Resemblance” is on view at Fridman Gallery, 287 Spring Street, New York, August 2–September 5, 2017.