From 1963 to 1968, Chiron Press was the ground-zero of the fledgling Pop Art scene. Founded in a tiny storefront on 614 East 11th Street in New York City, it was the first print atelier in New York City, indeed in the country, devoted to screen printing for artists. Andy Warhol (1928–1987), Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997), Larry Rivers (1923–2002), James Rosenquist (b.1933), and Claes Oldenburg (b.1929) were just a handful of the artists who made silkscreen prints at Chiron.

Roy Lichtenstein, Brushstroke, 1965

Chiron Press (named after the mythical centaur) was the brainchild of Steve Poleskie (b.1938), an artist who had worked for three months as a printer in Miami doing commercial screen printing jobs, a skill he picked up after reading a free booklet from the Sherwin-Williams Paint Company. In 1961, Poleskie moved to New York City and rented a studio on East 10th Street near Tompkins Square Park with the intention of furthering his art career. Since the 1950s, East 10th Street had been a hotbed of the downtown New York art scene. Abstract Expressionist painters such as Willem De Kooning (1904–1997), Franz Kline (1910–1962), and Milton Resnick (1917–2004) maintained studios nearby. The 10th Street Galleries—a series of artist-owned co-operative galleries, often run with no staff and very little money—formed a nucleus of alternative and avant-garde art spaces. The Judson Memorial Church, located on Washington Square South near East 8th Street, operated a gallery that debuted works by Tom Wesselmann (1931–2004), Jim Dine (b.1935), and Oldenburg in 1959.

Andy Warhol, Lincoln Center Ticket, 1967

Living on East 10th Street, Poleskie got to know many of the scene-makers of the day. He befriended Raphael Soyer (American, 1899–1987) while taking an art class at the New School. He also met Leo Castelli, a gallery owner who first featured many of the up-and-coming Pop artists.

Alfred Jensen, Duality Triumphant II, set of four, 1963

After fielding numerous questions from fellow artists about his techniques and methods, Poleskie realized that screen printing was in high demand, and in 1963, he opened a shop (initially called Aardvark Press) at 614 East 11th Street and became the master printer. He also hired future renowned Minimalist artist Brice Marden (b.1938) as his studio assistant. Within a short period of time, Poleskie was inundated with job requests. It seemed he was the only person around who not only knew how to make screen prints but, more importantly, could communicate with artists to translate their vision into a print. Since screen printing was, at that time, mainly used for commercial ventures such as billboard advertising, Poleskie’s artistic background and connections proved to be invaluable assets.

Artist Louise Nevelson (left) with Steve Poleskie (right) at Chiron Press, 1964

The very first set of prints made at Chiron Press was a suite of four by Alfred Jensen (1903–1981), an abstract artist who painted in grids of brightly colored triangles or squares, often incorporating systems of numbers into his work. Poleskie recalls that Jensen lived next door to the studio, and he could often hear the artist begging his dealer Martha Jackson to send him money. In the end, Jensen paid for the prints himself—the bill for the whole job was US$400.

Louise Nevelson, Blue Facade (from Facade – Homage to Edith Sitwell), 1966

With a long waiting list of galleries wanting their artists to do silkscreen prints, Poleskie was able to move the operation to 76 Jefferson Street on the Lower East Side. Because of its low rent and good light, 76 Jefferson Street became a magnet for artists such as Neil Jenney (b.1945), Janet Fish (b.1938), Valerie Jaudon (b.1945), and Richard Kalina (b.1946). In 1975, the MoMA mounted an exhibition called 76 Jefferson Street, a title that testified to the location’s importance as a center for artistic activity.

Nicholas Krushenick, James Bond Meets Pussy Galore (from NY Ten port), 1964

In the early years, Chiron Press had no fancy equipment. Poleskie used a handmade wooden table to make the prints, and clotheslines in lieu of drying racks. His only ventilation was an open window, and if he needed to use the phone, he had to go to the bar downstairs where the bartender would take messages. Though it became common practice in screen printing for artists to paint on clear acetate and then transfer the images photographically, Poleskie preferred to use real silk to support the stencils, which were all hand-cut, and to squeegee the prints by hand. The process was time consuming, but produced results in the brilliant, saturated colors that were so emblematic of the early 1960s, and which became the hallmark of Chiron Press prints.

Artist Helen Frankenthaler (left) with Poleskie (right) at Chiron Press, 1964

Chiron Press printed Lichtenstein’s very first screen print, Brushstroke, in 1965. The artist was working on a series of brushstroke paintings as a satirical response to the emotionally laden gestural paintings of Abstract Expressionism. But Lichtenstein was also interested in drawing a picture of a brushstroke that looked as though it had been rendered by a commercial artist. Since screen printing was a commercial process never intended for Fine Art, Brushstroke was a perfect graphic expression for Lichtenstein.

Helen Frankenthaler, Untitled, 1967

Warhol worked with Chiron Press on two occasions to make sculptural prints, which bore a resemblance to Oldenburg’s large soft sculptures of the period. The first, Paris Review (1967), was an enormous liquor bill, measuring 37×27 inches, with die-cut holes to resemble punched receipt holes. The other, Lincoln Center Ticket (1967), was an enormous ticket stub measuring 45×24 inches printed on opaque acrylic, and was published by the Leo Castelli gallery to commemorate the fifth New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center.

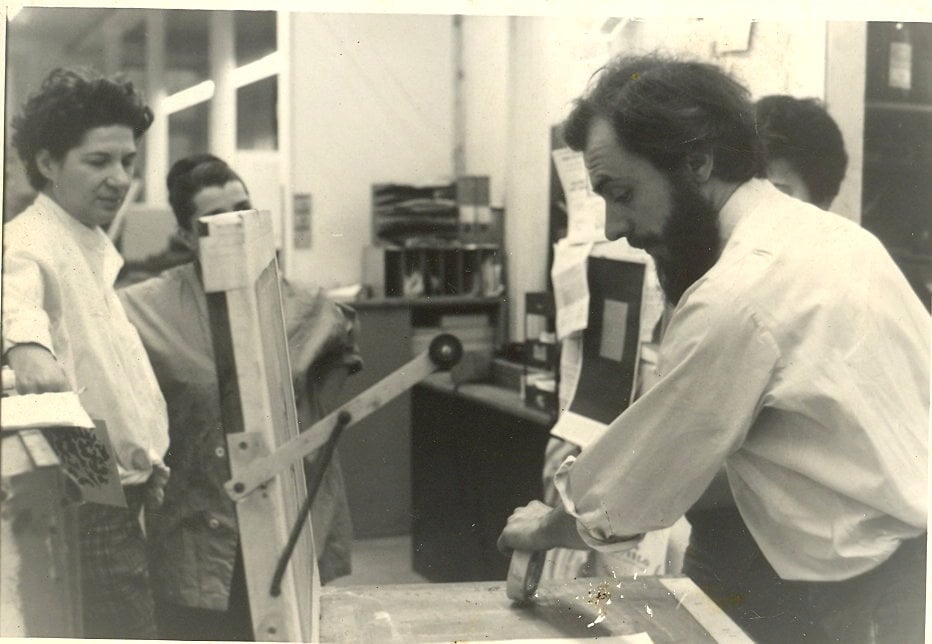

Artist Elaine De Kooning (left) with Poleskie (right) at Chiron Press, 1965

Chiron Press also worked with many female artists, including Marisol (b. 1930), Elaine DeKooning (1919–1989), and Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011).

Elaine de Kooning, Untitled, 1965

Pop Art was not the only focus of Chiron—in fact, the prints created there track the divergent artistic movements of the time. Nicholas Krushenick (1929–1999) made hard-edged abstract paintings with a Pop sensibility. His brilliantly colored silkscreen James Bond Meets Pussy Galore, made at Chiron in 1965, demonstrates a highly original vision.

Artist Richard Anuszkiewicz (left) with Poleskie (right) at Chiron Press, 1964

Poleskie’s own prints, created at Chiron during 1967, were abstract and geometric meditations on landscapes. He has remarked that living in a crowded city such as Manhattan meant that he could only imagine the landscape, saying, “I lived in the city and thus could not see the land, but it was there—in the advertisements, behind the cars, the soda pop, [and] the cigarettes.”

Nicholas Krushenick, Steve Poleskie, Larry Rivers, and Larry Zox pose for a poster in Union Square, New York City, NY, 1967

In 1968, Poleskie sold Chiron Press so that he could devote more time to his own artwork. He moved to Ithaca, NY, and accepted a teaching position in the art department at Cornell University, where he is now professor emeritus.

Steve Poleskie, Patchogue, c.1966

Despite its brief five-year run, Chiron Press was responsible for a major shift in how artists used screen printing in their creative processes. Screen printing has risen from an industrial process to a Fine Art form. The sheer number of influential artists who made prints at Chiron Press reads like a who’s-who of the 1960s art world, and many of those artists would go on to achieve art superstar status.

Steve Poleskie, Sea Target, c.1967