Call it a tale of two objects.

In late March, after scanning the online catalogue for Christie’s upcoming antiquities auction in New York, an archaeology expert flagged two objects that he believed had potentially questionable provenance. After matching them with pictures of what he described as identical objects associated with notorious traffickers, he alerted the authorities.

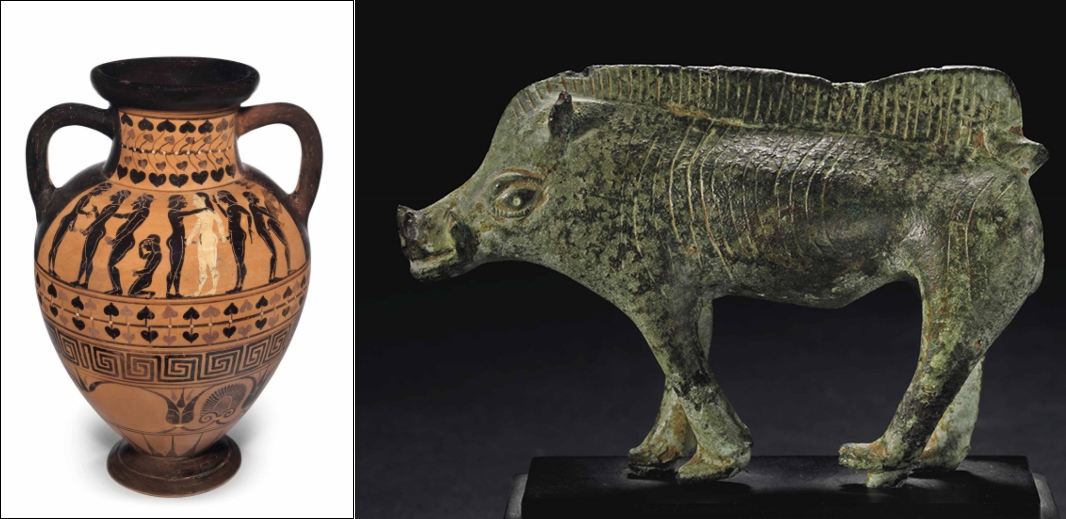

By the time his concerns were reported on a blog known as ARCA (the Association for Research into Crimes Against Art) on April 11, one work—an Etruscan “Pontic” black-figured neck-amphora attributed to the “Paris Painter” and dated circa 530 BC—had already been withdrawn from the sale. It had been estimated to sell for between $30,000 to $50,000.

However, the second work, a Roman bronze boar, circa 1st–2nd century AD, remained on offer. At the auction on April 18, it sold for $15,000, near the high end of its $10,000–15,000 presale estimate.

Why the different outcomes?

“It’s the game of the market,” Christos Tsirogiannis, the Greek, Cambridge-based forensic archaeologist who first flagged the two works, told Artnet News. “I’m not surprised at all.”

Indeed, the differing results are emblematic of the broader challenges facing the trade when it comes to identifying problematic objects. Not everyone has access to the same information—or is equally induced to go the extra mile to track it down.

A Thorn in the Side of Auction Houses

Over the past 14 years, the now 44-year-old Tsirogiannis has taken it upon himself to conduct this type of independent research. He has earned a reputation as a tireless sleuth and a “thorn in the side of auction houses,” as one colleague put it. His research has contributed to restitution by museums including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and Los Angeles’s J. Paul Getty Museum.

In this case, Tsirogiannis concluded the works might be problematic after matching them with two objects listed in confiscated archives: those of Gianfranco Becchina and international dealer duo Robin Symes and Christo Michaelides.

Becchina is an Italian dealer whose business records—140 binders with more than 13,000 documents related to the sales of antiquities—were confiscated by Swiss and Italian authorities in 2001. According to Tsirogiannis, at one point or another, all of the objects documented in his archive were known to have passed through his network of illicit suppliers. Translation? The mention of the name Becchina alone sends up a red flag.

Pictures of the amphora documented in the confiscated archives of Gianfranco Becchina.

Courtesy of Dr. Christos Tsirogiannis.

Tsirogiannis found two photos in the Becchina archive that show the amphora prior to its restoration, still broken in many fragments and encrusted with soil and salt. According to the provenance on Christie’s website, the current owner acquired it from a dealer in Freiburg, Germany, in 1993. Becchina’s name does not appear in the ownership history.

As for the second object, the bronze Roman boar, Tsirogiannis says he matched it to two photos in the Symes-Michaelides archives, which were confiscated by police in 2006.

Symes and Michaelides dominated the international antiquities market for most of the 1980s and ’90s. Many of the works they sold were sourced from Becchina and another dealer who was ultimately convicted of trafficking, Giacomo Medici.

Although Symes was never formally convicted of antiquities trafficking (a British court convicted him only of contempt of court), Tsirogiannis says he and his partner’s names are notorious in the trade. The researcher believes more than 90 percent of the works in the archive “appear to be of illicit origin.”

Bronze Roman boar as documented in the Symes/Michaelides archive. Courtesy of Dr. Christos Tsirogiannis.

A Chain of Identification

Once Tsirogiannis gathered his evidence, he alerted Interpol and the Manhattan District Attorney’s office. Specifically, he reached out to Matthew Bogdanos, the marine turned New York assistant district attorney, who is leading a new antiquities trafficking unit that has recently executed high-profile seizures from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and collector Michael Steinhardt, among others.

The district attorney’s office declined to comment, but a source told Artnet News that the withdrawal of the amphora from the antiquities sale was prompted by information Bogdanos presented to Christie’s about the work.

A spokesperson for Christie’s told Artnet News: “Following the distribution of the sale catalogue, information came to light that had previously been unavailable to our team of specialists. This information led us to withdrawing [this work] pending further research. Christie’s is extremely pleased that information has come to light in good time in order for these matters to be addressed effectively and efficiently.”

Why didn’t Tsirogiannis go directly to Christie’s? “No—you don’t go to the trafficker to alert them,” he said.

Indeed, over the years, Tsirogiannis says he has developed a reliable method for flagging such works (though this method hasn’t endeared him to the trade). Every time he identifies an object connected to convicted or suspected traffickers, he notifies Interpol first, then the judicial authorities or police in the country where the sale is due to take place, and finally, depending on the quality of the evidence, authorities in the source country that might have a claim on the identified object.

This approach has frustrated some in the antiquities business, who complain that Tsirogiannis is one of very few experts with access to the Becchina, Medici, and Symes-Michaelides archives. Without access, dealers say, it is difficult to do a comparable level of due diligence. (The archives are technically owned by the Greek and Italian states, which have so far declined to make them public; Tsirogiannis has said that publishing the records could alert bad actors and push the market for illicit antiquities further underground.)

More to Be Done?

It is unclear exactly why Christie’s chose to withdraw the amphora but move ahead with the sale of the boar. (A spokeswoman declined to comment on the subject.) It is possible that the evidence was simply not as iron-clad; some have also claimed that objects associated with Symes are not as universally tainted as those associated with Becchina.

Furthermore, the boar passed through the hands of a number of known collectors before arriving at Christie’s. (Tsirogiannis calls this phenomenon “laundering provenance”: an object can appear more pristine through its association with venerable buyers, just as it can appear more suspicious through association with shady dealers.)

The boar’s previous owners include Christos G. Bastis, the late Greek-born, US-based businessman and antiquities collector. His collection—including the boar—was sold at Sotheby’s the same year he died, in 1999. But Tsirogiannis says he identified the boar in the Symes-Michaelides archive more than a decade ago—and it’s not the only work in his collection to appear there. “I have identified several objects in his collection that also appear in the confiscated Symes archive,” he said.

Roman Bronze Boar, (ca. 1st–2nd Century A.D.) as depicted in Christie’s catalogue. Courtesy Christie’s.

Although Tsirogiannis has acknowledged that Christie’s and other businesses may be at a disadvantage because they don’t have access to the same archives, he still believes the auction house’s due diligence fell short of the mark. “Either the due diligence is not happening or they do know and exclude the names [of the problematic dealers associated with the works], which is even more troubling,” he told Artnet News.

He insists that the auction houses can, but choose not to, do the same level of research he conducts. Even without access to the archives, they can still consult the relevant authorities—like the governments of Greece and Italy—to see if a work appears. And if auction houses are concerned about breaching client confidentiality in the process, collectors themselves can seek out the relevant authorities before consigning objects to auction, he adds.

As cases of seizure and repatriation are on the rise in New York and elsewhere, association with a well-known collector or museum can no longer afford a safety net, Tsirogiannis says. “Why would someone go and put their money and reputation behind an object that sooner or later may—especially with additional evidence to solidify—be proved illicit?”