Chuck Close, whose distinctive, monumental portraits and self-portraits toyed with viewers’ perception, has died of complications from a long illness that led to congestive heart failure, according to Pace, his gallery since 1975. The artist, who faced a reckoning in recent years after numerous women accused him of sexual harassment, was 81 years old.

“I am saddened by the loss of one of my dearest friends and the greatest artists of our time,” Pace founder Arne Glimcher said. “His contributions are inextricable from the achievements of 20th and 21st-century art.”

Born in Monroe, Washington, in 1940, Close struggled as a child in school due to undiagnosed dyslexia. But he managed to get through community college and earned his bachelors degree at the University of Washington, developing his own methods of overcoming his learning disabilities.

This adaptability proved helpful later in life, when spinal artery collapse in 1988 left Close paralyzed and he found new ways to paint while using a wheelchair. He devised a method of working with a brush strapped onto his wrist. (The unique process was expertly documented in Marion Cajori’s 2007 documentary Chuck Close: A Portrait in Progress.)

Chuck Close painting in his studio. Photo courtesy of Pace Gallery.

“I’ll spit on the canvas if I have to,” he told friends of his determination to continue making art, according to the BBC.

Close’s career was bookended by controversy. His very first solo show, in 1967, was at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, where he was teaching at the time. School officials shut it down because it contained explicit male nudes. The case went to court, with the American Civil Liberties Union advocating on the artist’s behalf. Close won, but left the school to move to New York City. (The decision was later overturned on appeal.)

In 2017, at the height of the #MeToo movement, Close was accused by two women of having sexually harassed them when they came to his studio to pose as models. More accusations followed, alleging that between 2005 and 2013, the artist had made inappropriate comments about the women’s bodies and asked sexually inappropriate and invasive questions. None alleged physical assault.

The fallout sparked broader debates within the art world about how the field should respond to such allegations, under what circumstances the art should be separated from the artist, and how to ethically work with nude models,

Chuck Close at the 2016 MoMA Party in the Garden Benefit at the Museum of Modern Art, New York Ciity. Photo by Liam McMullan ©Patrick McMullan.

Close apologized, but the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., indefinitely postponed a planned exhibition of Close’s work. (It has yet to be rescheduled.) His only shows since have been a joint outing at Pace and White Cube in Hong Kong in 2020, and a Gary Tatintsian Gallery show, co-organized with Pace, currently on view in Moscow through September 25.

Close’s neurologist, Thomas M. Wisniewski, told the New York Times that the artist’s behavior could have been caused, at least in part, by frontotemporal dementia, with which Close was diagnosed in 2015. (He did not address the fact that the alleged behavior preceded the diagnosis by a number of years.)

“He was very disinhibited and did inappropriate things, which were part of his underlying medical condition,” Wisniewski said. “Frontotemporal dementia affects executive function—it’s like a patient having a lobotomy—it destroys that part of the brain that governs behavior and inhibits base instincts.”

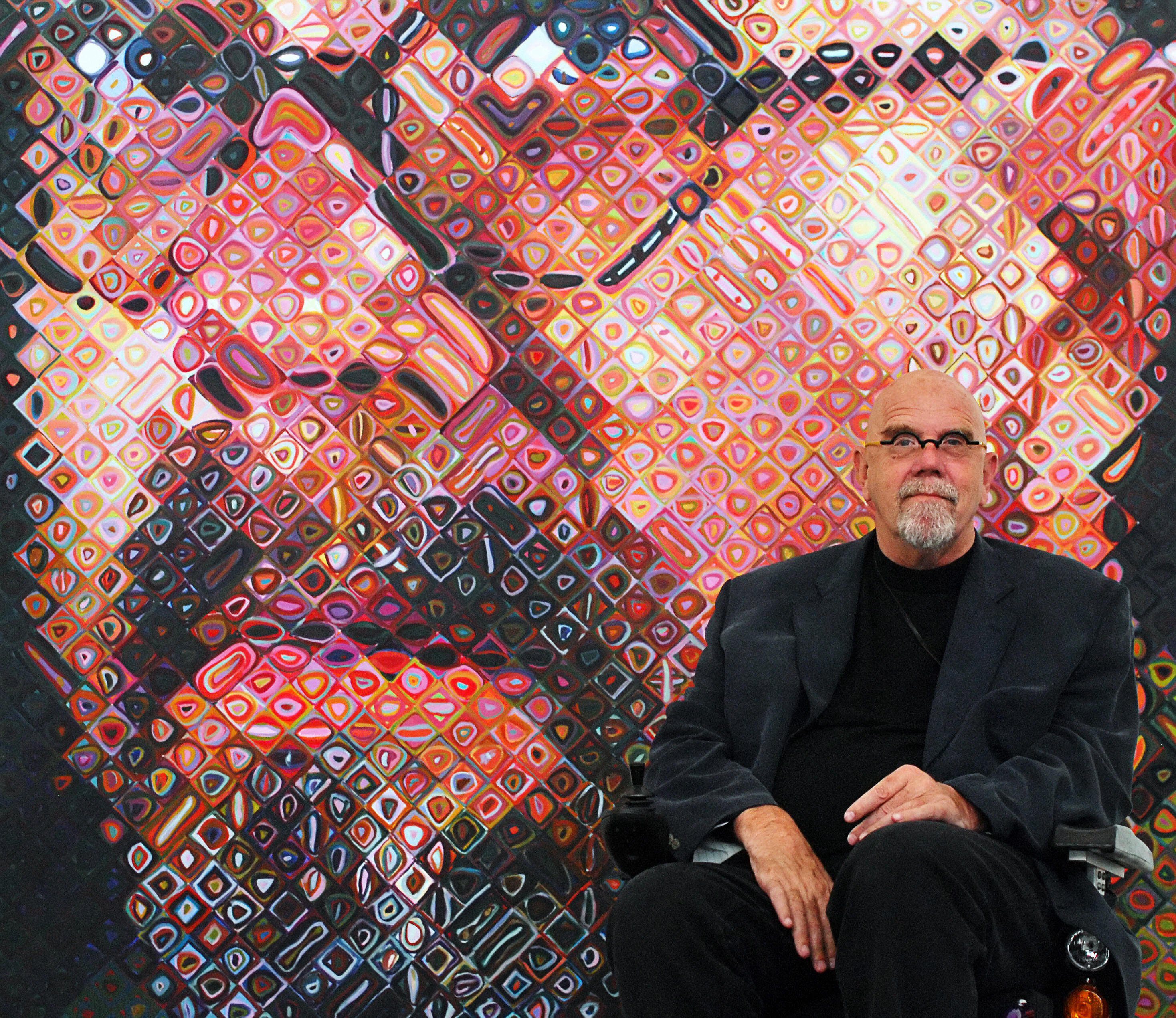

Chuck Close, Self-Portrait I (2015). Courtesy of Pace, ©Chuck Close.

Art came naturally to Close, who as a child suffered from a neuromuscular condition that made it difficult for him to engage in physical activities. Instead, he did magic tricks and drew to entertain his friends.

But it was the Vietnam War that inspired him to pursue art formally—Close enrolled at Yale University’s art masters program in 1962 to get a student deferment and avoid the draft. There, he studied alongside Richard Serra, Brice Marden, and Vija Celmins, among other future art stars.

During school, Close worked in the Abstract Expressionist style, but began making giant black-and-white Photorealist airbrush paintings based on photographs while at the University of Massachusetts. Around that time, artists such as Richard Estes and Robert Bechtel were gaining attention for their Photorealist paintings, but Close put his own distinct spin on the style.

One of those early works, a head-on self portrait of the artist staring at the camera and smoking a cigarette in extreme close-up, became his breakthrough. Titled Big Self-Portrait, it remains one of his best known, and was acquired by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis for just $1,300 in 1969. (The museum would give Close his first major museum retrospective in 1980, which traveled to the MCA Chicago and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.)

Chuck Close with his Big Self-Portrait, (1967–68), photographed in his studio in 1968. Photo by Kenny Lester ©Chuck Close/courtesy of Pace Gallery.

After mastering a three-color process, capturing every hair and imperfection in minute detail, Close developed a groundbreaking grid system in the 1970s, dividing both the painting and the source photograph into squares to recreate the image on the canvas.

Once Close became quadriplegic, the grid allowed him to keep going in pointillistic fashion, filling each square with bold, sometimes garish strokes of color, the face coming into focus only as the viewer steps away from the canvas. The result almost appeared pixelated.

Close had been experimenting with this fragmented effect before losing his mobility—a 1998 retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art demonstrated as by comparing works from the year before and after.

Chuck Close painting in his studio in the 1970s. Photo ©Chuck Close/courtesy of Pace Gallery.

“There’s an obsessiveness there that is extraordinary,” art historian Tim Marlow, director of exhibitions for London’s White Cube gallery, told the Guardian in 2005. “It has made [Close] a kind of lone figure in contemporary art—no one else is doing what he is doing. He has reinvented portraiture through the medium of paint, but also abstracted it. He’s a painter’s painter, but his reputation is still growing. I’d put him among the top 10 most important American artists since Abstract Expressionism, no question.”

Close’s portraiture brought him international fame, but the practice of making it was also quite utilitarian for the artist, who said he suffered from prosopagnosia. More commonly known as face blindness, the condition meant he was unable to recognize people, sometimes even when he knew them well. Putting their faces down on canvas, he said, helped.

“Once I change the face into a two-dimensional object, I can commit it to memory. I have a photographic memory for things that are two-dimensional,” Close told the Society for Neuroscience in New Orleans, according to the Tampa Bay Times.

Artist Chuck Close. Photo by Michael Loccisano/Getty Images.

Many of Close’s subjects were celebrities, including Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, Brad Pitt, Kate Moss, George Lucas, Lou Reed, Paul Simon, and Philip Glass. But he also painted family and friends, including artists such as Serra, Alex Katz, Cindy Sherman, Kara Walker, and Cecily Brown. His portrait of Bill Clinton is in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

In later years, Close continued to explore new means of working, translating his portraits to textiles and even subway tiles, creating a series of mosaics for the 86th Street station on the 2nd Avenue Subway line in New York. His work encompassed printmaking, drawing, collage, daguerreotype, tapestries, and Polaroid photography.

Close was also a staunch advocate for arts education, noting frequently that his dyslexia made other subjects difficult and that art was the only class that kept him engaged. As a member of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities during the Obama administration, he helped develop Turnaround Arts, a program that aimed to make arts a centerpiece of education at select schools.

Chuck Close mosaic mural made for the subway’s 86th Street-Second Avenue station. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Transit Authority and Arts for Transit.

“Because of his early and unwavering support, we were able to bring the arts to tens of thousands of schoolchildren across the country,” Rachel Goslins, the former head of the committee, told Artnet News.

Married and divorced to two artists, Leslie Rose from 1967 to 2011, and Sienna Shields from 2013 to 2015, Close is survived by daughters Georgia and Maggie, four grandchildren, and his half brother, Martin Close.

Close’s work can be found in the collection of such institutions as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney, and the MoMA in New York; the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The artist received the National Medal of Arts from President Clinton in 2000.

Additional reporting by Sarah Hanson.