A U.S. district court in Vermont has ruled that Vermont Law School can conceal a large public artwork about slavery that has divided viewers for years because of imagery that some deem offensive and cartoonish. The judge rejected the artist’s argument that doing so would violate his rights under VARA, or the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990.

In a decision dated October 20, Chief Judge Geoffrey W. Crawford granted the school’s request for summary judgment and reiterated an earlier ruling in the case—when the artist sought an injunction— that “the text of the VARA does not protect against the concealment or removal from display of artworks.”

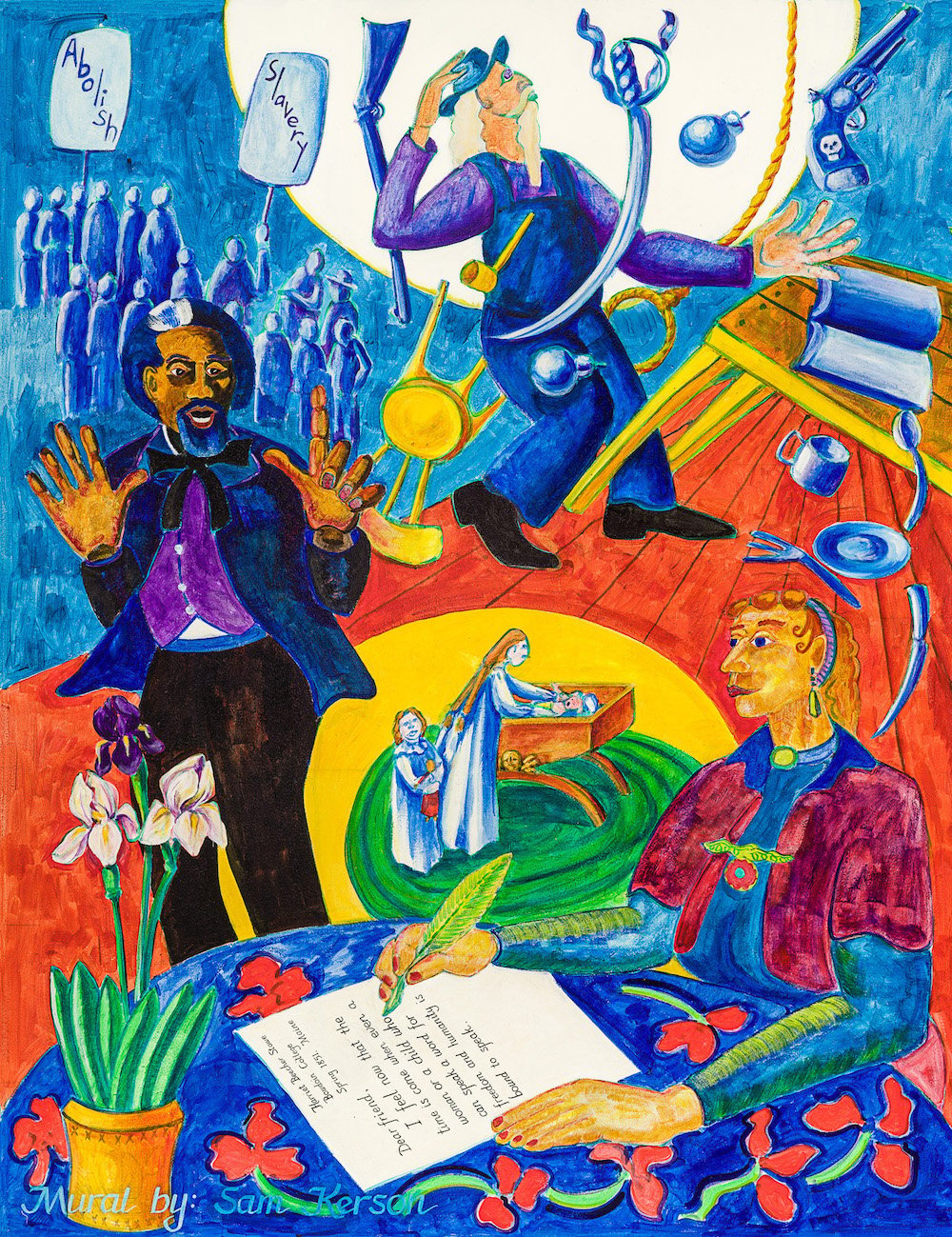

The artist Samuel Kerson painted the works in 1993 on the walls of the law school’s Jonathan B. Chase Community Center in Royalton, Vt. Collectively titled The Underground Railroad and the Fugitive Slave, the dual panels (dubbed “Slavery” and “Liberation”) were intended to depict the evils of slavery and the actions of abolitionists and activists in Vermont who aided slaves seeking freedom on the Underground Railroad.

Since at least 2001, the school had fielded complaints from students who expressed discomfort with the murals. Some described the images as “cartoonish, almost animalistic” depictions of enslaved African people, according to court papers.

“We are disappointed by Judge Crawford’s decision and will be taking an appeal to the Second Circuit,” said Kerson’s attorneys, Steven Hyman and Richard Rubin, in an email to Artnet News. They called it “unfortunate that more than 25 years after Vermont Law School asked Mr. Kerson to paint these two 24-foot murals commemorating Vermont’s role in the Underground Railroad and celebrated its completion, it now is intent on permanently covering them from view.” Concealing the murals is “an affront” to the artist’s honor and reputation, they added.

The school’s counsel wrote in an email to Artnet News, “We are very pleased that the Court has vindicated Vermont Law School’s right to cover the Kerson mural,” said attorney Justin Barnard. “[I]t became clear over recent years that the mural—which many feel depicts Black bodies in a caricatured, stereotyped manner—was inconsistent” with the school’s mission, and had become a source of discord.

The school also released a statement, saying that it will now, with the court’s approval, “be able to cover the mural in support of our students and community members who find the mural offensive because of how it caricatures enslaved Africans specifically, and casually stereotypes Black bodies in general,” according to board chair Glenn J. Berger.

Samuel Kerson, “Walking Up To Vermont,” detail of The Underground Railroad and the Fugitive Slave (1993). Image courtesy of the artist.

In 2013, the school attached plaques to the wall next to the artworks explaining the purpose of the mural and its intent to depict the shameful history of slavery as well as Vermont’s role in the Underground Railroad. However, calls to remove them grew louder last year in the wake of the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, as social justice movements and protests swept the U.S. and the world.

When some of the school’s leaders agreed that the works should be removed, its president, Thomas McHenry, sent Kerson a letter notifying him of the intent to remove or cover the murals permanently and gave the artist the opportunity to remove the murals himself, along with the offer to return full ownership.

One point Kerson and the school do agree on is that the sheetrock cannot be removed without damaging the murals. When Kerson sued the school in December, he moved for a preliminary injunction, asking the court to bar the school from covering the mural while the lawsuit was pending. The court ruled on and denied that motion in March.

The school’s proposal to conceal the murals is not only extraordinarily detailed, it seems to have factored into the judge’s opinion that it is permissible, since it does not directly damage or alter the works. Per the proposal the artwork will be covered by “building a wooden frame around the murals that will support acoustic panels. The panels will permanently conceal the murals from view. Neither the frame nor the panels will actually touch the murals.”

Judge Crawford explored questions of modification as they relate to VARA and wrote: “Few would describe concealing the mural as a ‘distortion’ or a ‘mutilation’.” He also cited a landmark VARA case from 2010 involving the artist Christopher Buchel and the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (Mass MoCA), writing: “One other court decision has ruled that concealing an artwork from view is not a modification or distortion.”

The case bears similarity to a 2017 furor centered on a set of murals by Thomas Hart Benton in a classroom at Indiana University that depicted hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan. When 1,600 people signed on to a letter asking the school to take down or conceal the offending panel, the school responded by no longer holding classes there in hopes of addressing the controversy without actually removing the artwork.