This piece is the second in a three-part series that explores the potential art-world impact of cryptocurrency. It proceeds as if the reader is already familiar with the core concepts and related terminology covered in Part I. If cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology are new to you, we highly recommend starting from the beginning. The series concludes with Part III.

After Francis Bacon’s Three Studies of Lucian Freud (1969) sold at Christie’s New York in 2013 for a then-unprecedented $142 million, New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl penned a blog post simply titled “The Circus.” He didn’t just use it to side-eye the mind-warping prices at the market’s peak. He questioned the entire concept of an art market, period, by acknowledging that Bacon and Freud were both “obviously worth something”—but only “given the spooky assumption that art is worth anything.”

A few years later, the fraught relationship between art and value lies at the molten core of several pieces made using blockchain technology. Part one of this series addressed how, in theory, the blockchain strengthens the markets for new media by introducing the concept of digital scarcity. This innovation means that works as simple as an “original” JPG or GIF could be made as rare as Francis Bacon paintings. (This fact leads to a host of business implications that will be covered in Part III.)

However, a handful of forward-looking artists is using the blockchain to do more than reset the market’s perception of supply and demand. The technology, their work proves, is more than new software—it’s also a new medium.

Bitchcoin’s logo.

Courtesy of the artist.

Currency Exchange

Blockchain-based work probably first surfaced in art-world consciousness in the form of Sarah Meyohas’s Bitchcoin (2015). The project was a natural manifestation of the New York-based artist’s central interests, which she characterizes as “how you create value, what value is, and what value means,” as well as how value can be represented.

The word “Bitchcoin” refers to two intertwined elements of the same project. First, Bitchcoin is the name of a niche cryptocurrency Meyohas created after immersing herself in blockchain subculture beginning in late 2014. Bitchcoins were never traded on any official third-party crypto exchanges such as Coinbase. But their rules were written into a corresponding white paper, and 200 of the digital tokens could be purchased from Meyohas directly after the launch at a fixed price of $100 each.

Meyohas believed then that “no one was going to consider [Bitchcoin] valuable unless there was something backing it.” So just as the US dollar was once backed by gold, Meyohas decided to back her cryptocurrency with a tangible asset: Speculation (2015), a photographic edition of eight specifically made for the project.

Stay with me: The particulars here are crucial. In the corresponding white paper, Meyohas guaranteed each individual Bitchcoin with a five-inch by five-inch segment of one of the associated, available editions of Speculation. Therefore, a collector who acquired 25 Bitchcoins (at a total price of $2,500) controlled 625 square inches of one Meyohas photograph—just enough for the entirety of the work (sized a bit under 22 inches by 29 inches). And at that point, if they chose, they could trade in their Bitchcoins for ownership of a physical piece whose value would rise or fall as Meyohas’s career progressed.

Setting aside the question of future value, it sounds like a straightforward system of exchange: Cash becomes Bitchcoin; Bitchcoin becomes a photograph. The transaction itself is only technologically different from, say, a Starbucks gift-card purchase: Cash becomes a rectangle of plastic; a rectangle of plastic becomes a Mocha Frappuccino the size of a fire hydrant.

Practically speaking, then, the most significant distinction between a Bitchcoin transaction and a gift-card transaction is that the former gets tracked on the distributed digital ledger that is the Bitchcoin blockchain.

Yet the underlying technology was less intriguing to Meyohas than what it enabled offline.

More Than Meets the Eye

Meyohas sees Bitchcoin as an example of relational aesthetics—a genre in which an artist’s work consists of engineering human interactions in the wider world. Think: Art as social participation.

“Ultimately,” Meyohas explained of her micro-economy, “it’s about trust.” The blockchain provides an incorruptible digital record of debts, but that record is worthless without the cooperation of the actual humans involved. Every Bitchcoin transaction can only take place if all necessary parties play by the established rules.

In that sense, the blockchain aspect can be irrelevant—or even inscrutable—to collectors buying into Meyohas’s cryptocurrency. What matters is how they think and act in response to her value-exchange regime. This is the second—and no less important—element of the project. “You don’t need to know how the system works in order for the system to work,” Meyohas noted about not just Bitchcoin’s technology but, more broadly, the technology underneath any economic model.

Just think: How many people who regularly swipe a Visa or American Express could easily explain the machinations behind credit cards? What percentage of Paypal users have rigorously examined the digital architecture underneath their last Etsy purchase?

So Bitchcoin (the cryptocurrency) merely extended a ladder up to Bitchcoin, the window onto human behavior.

And since the launch of Bitchcoin, other artists have begun wielding blockchain technology to open that inquiry even wider.

Promotional image for Elliott Arkin and Marc Lafia’s Salvator Mundi Cryptocurrency. Courtesy of the artists.

For the Love of God

Relational aesthetics are also the motor powering a project by Elliott Arkin and his sometimes collaborator Marc Lafia—one that, in my eyes, furthers the conceit of Bitchcoin by eliminating any actionable connection to the physical world. Just don’t make the mistake of reading their soon-to-launch Salvator Mundi Cryptocurrency too literally.

“It’s a currency only in name,” Lafia explained to me over the phone. “The currency is the work, and vice versa.”

Arkin and Lafia began pursuing the project after the former, in his characteristically mischievous fashion, opened an online store called Real Salvator Mundi a few days after the sale of the record-annihilating Leonardo in November. Intended to embrace the ridiculous, the shop offers an array of products branded with the public-domain image of everyone’s favorite orb-clutching Christ, from t-shirts and panties to playing cards and a “DIY restoration kit” (an A+ troll of the painting’s much-publicized condition saga).

Arkin explained Real Salvator Mundi as a means of “taking back possession of this image after [the painting] sells for this crazy amount. That’s what Marc told me was involved in cryptocurrencies, as well.” In other words, the goal was to use mass participation to democratize a masterpiece alienated from the public by the apex of the collecting class. So what could be more natural than adding a themed cryptocurrency to the product line?

Enter what, for brevity’s sake, its creators shorthand as Mundicoin.

It sounds like a lark at first. However, Lafia, a conceptual artist deeply engaged with new technologies and participatory art, had been thinking through blockchain’s aesthetic possibilities for some time. In particular, he had become intrigued by the prospect of “making a work that is its own value.”

Value Proposition

Unlike Bitchcoin, Arkin and Lafia’s cryptocurrency is only backed by a philosophical conceit—which is to say, no tangible asset at all. Like all conceptual art, it becomes an artwork through the collective participation of a willing audience. It is only valuable—either culturally or financially—if enough people agree it is. As Lafia explained, “There’s no utility, but you can still buy it and sell it.”

This dynamic informs even the most traditional works, whether we’re talking about Three Studies of Lucian Freud or Salvator Mundi itself. A select group of interested parties builds value in objects through scholarship, exhibitions, and other awareness-raising efforts. But these efforts only matter if a somewhat larger audience accepts their message. If Salvator Mundi goes on a world tour but no one gasps in its presence in a viral video, was it really a masterpiece?

From a valuation standpoint, then, Lafia argues that what mainly distinguishes Mundicoin from Salvator Mundi is transparency. Everyone who literally buys into his and Arkin’s cryptocurrency “is in on the joke. The [valuation] mechanism”—specifically, its underlying absurdity—“is clear, and that’s what blockchain is all about. Collective participation is integral to the underlying technology.”

In that sense, one could argue that cryptocurrencies are the perfect technological expression of Schjeldahl’s “spooky assumption that art is worth anything,” and that Mundicoin rattles the cage loudest.

Yet it would be a mistake to believe that blockchain-based artwork can never transcend the art world’s closed system of value.

Julian Oliver’s Harvest (2017). Courtesy of the artist.

Reap What You Sow

Berlin-based artist and engineer Julian Oliver has used cryptocurrency as a tool to battle one of our most pressing problems: climate change. He sought to use our planet’s increasingly volatile weather conditions to counter their root causes. The result? Artwork as ecological judo-throw, with cryptocurrencies as the leverage point.

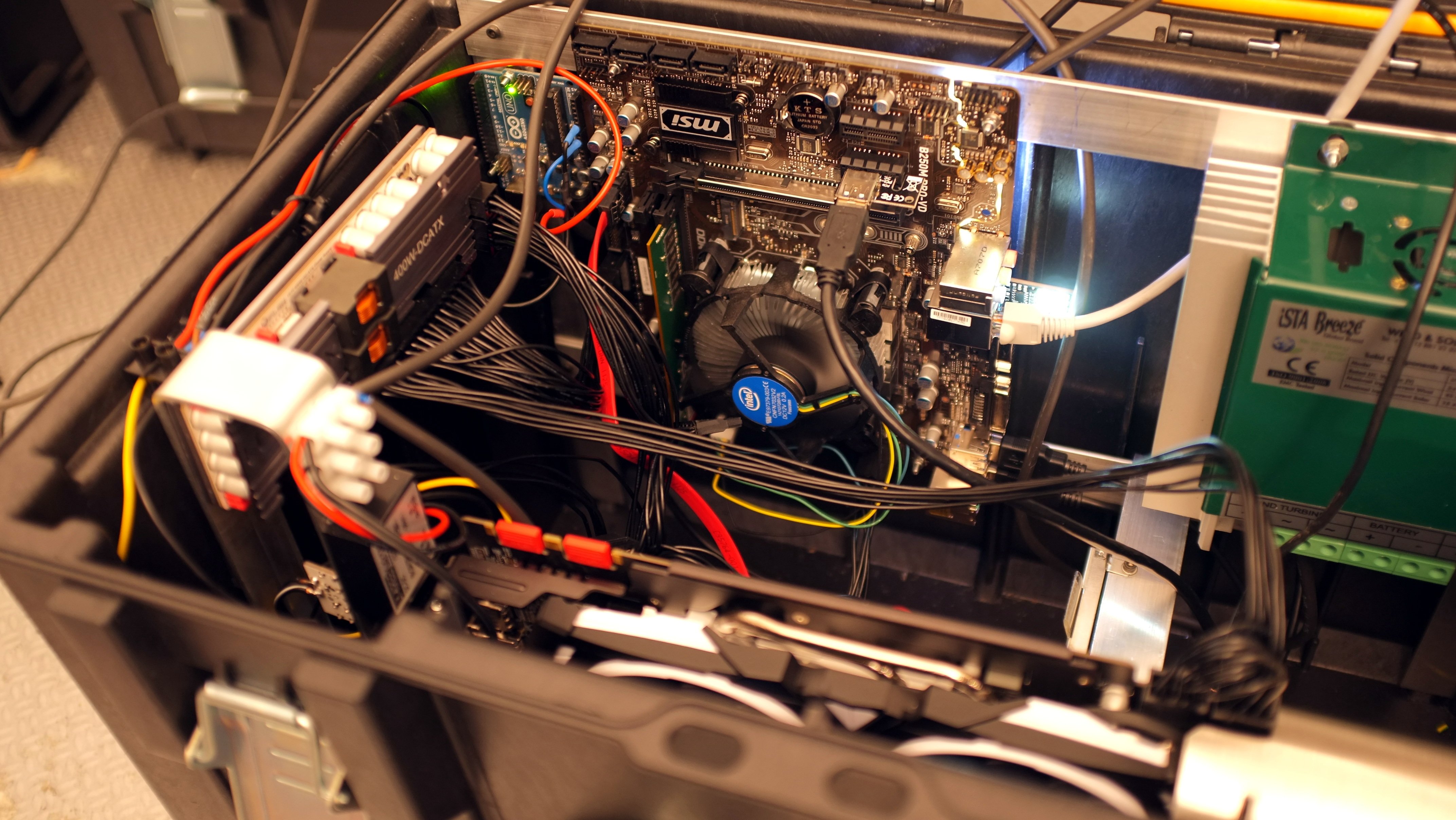

Commissioned by Sweden’s Skövde Konstmuseum, his installation Harvest (2017) consisted of two physical parts: the first, a sensor-equipped wind turbine connected to a weatherproof computer, stationed in an open field in Germany’s Brandenburg region; the second, a live video feed and data visualization (designed by digital artist Christopher Pietsch) tracking the rig’s status, which was projected onto screens inside the museum.

The turbine’s job wasn’t just to generate clean power throughout the exhibition’s two-month run. It was also to direct that clean power into mining a lesser-known cryptocurrency called Zcash. (Since Bitcoin mining in particular is often criticized for consuming tremendous amounts of electricity to power legions of number-crunching computers, substituting wind energy allowed Harvest to work in an environmentally conscious way.) Then, Oliver donated all proceeds of his installation’s mining efforts to a group of nonprofits focused on researching and raising awareness about climate change.

Although Oliver describes this first installation of Harvest as “a prototype,” it might be more accurate to describe it as proof of concept. He confirms that the rig generated about $620 in mining profits during its roughly 10-week trial. “While that might not seem like much,” he says, “it’s a lot more than most individuals donate in the same period.”

In fact, the real value proposition is that, outside of the initial setup and occasional monitoring of the equipment, no humans need to be involved in the operation at all. Oliver describes the Harvest rigs as “funding automatons” that can each be built for around $2,500.

The modest financials introduce the prospect of economies of scale. Oliver mentions that he is now in the midst of optimizing the original rig in order to, he hopes, produce more in partnership with organizations battling climate change around the world.

He is even designing “a small mining farm fed by a 10kW turbine that will reliably earn between 12X and 30X more” than the initial single-turbine installation. (At present the project will be self-funded on privately owned land, although Oliver says he remains open to potential partners who share his nonprofit-oriented vision.) He estimated that this expanded setup could sustainably fund a small NGO on its own.

Despite his grand ambitions, Oliver points out that there is nothing inherently utopian about the blockchain itself. Like nearly every technological innovation, its effects depend on what aims people use it for.

Where Do We Go Now?

“While Bitcoin went on to mirror the same exclusionary and gluttonous logic endemic within the traditional financial system,” Oliver says, more than 1,000 other cryptocurrencies have since emerged, some of which are “built to maintain an even distribution of wealth, or fund artists, scientific research, etc.”

Nor is decentralized smart money, as it’s sometimes known, the be-all, end-all of the technology. “Beyond currency,” Oliver continues, “blockchains offer a single digital platform for the public collection, preservation, and verification of a growing body of evidence, something that has never existed before in a digital context.”

There are other artists and art professionals already working toward more advanced uses and applications for this body of evidence. We’ll investigate their progress—and its potentially disruptive implications—in Part III.