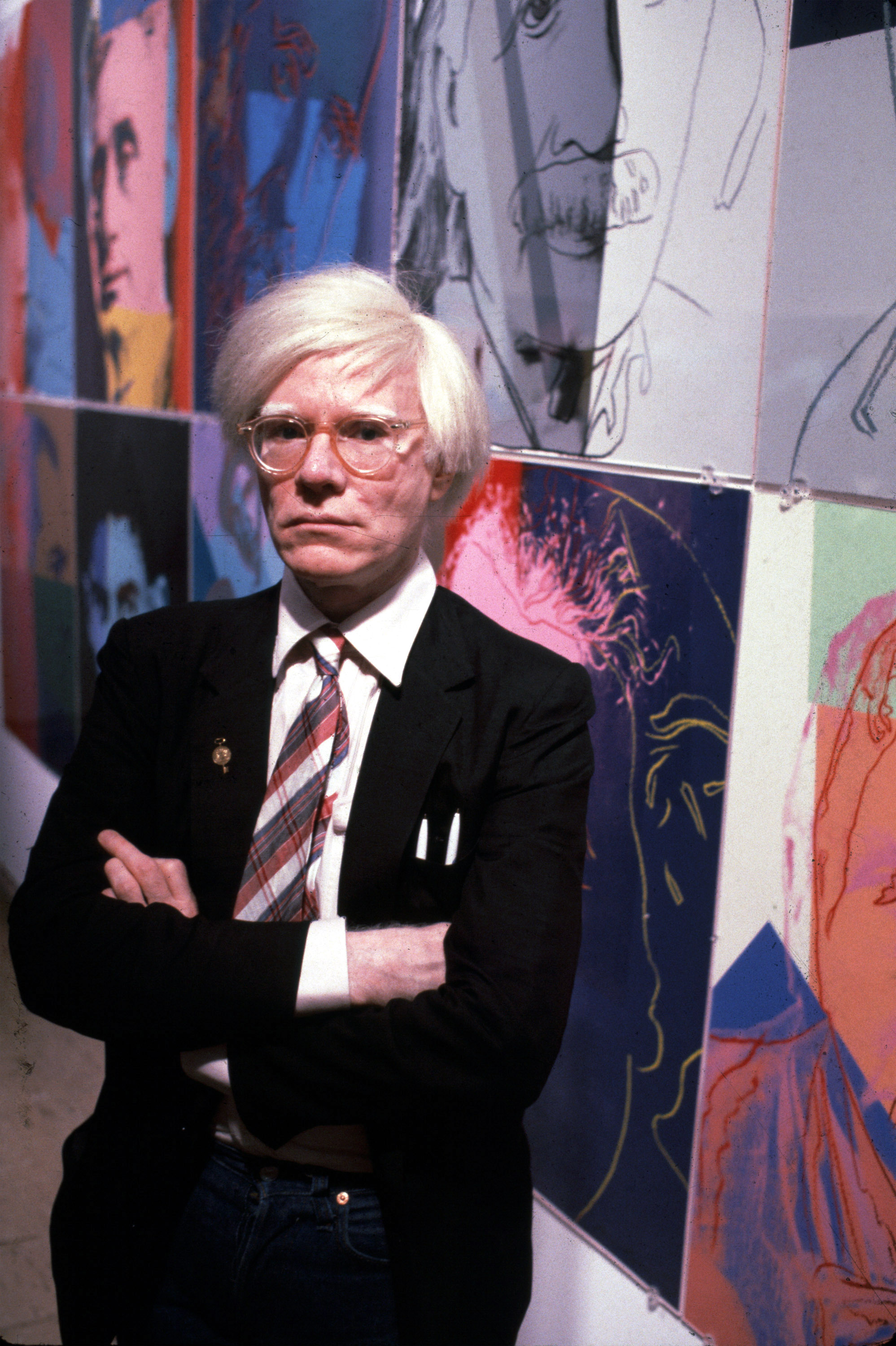

When Donna De Salvo first met Andy Warhol in 1985, she was a young curator working at the Dia Art Foundation. He was a middle-aged artist, known for wearing a funny wig—and not particularly in vogue.

“People were not paying attention to his work,” says De Salvo, who is now deputy director for international initiatives and senior curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. “He was the guy who just goes to a lot of openings.”

Donna De Salvo. Photo: Scott Rudd.

De Salvo’s personal history with the iconic artist has done much to inform “Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again,” which opens at the Whitney on November 12. Although few contemporary artists have been the subject of as many exhibitions worldwide as Warhol, De Salvo aims to offer a unique perspective on his work—a personal one. She looks behind Warhol’s carefully constructed mask to explore how a gay man raised by Czech immigrants in a Catholic family became one of the world’s most experimental artists.

“I found there was something actually very earnest about him,” says De Salvo, who has put together four Warhol exhibitions over the course of her career. Her fifth, the Whitney show, is the largest on the artist organized by an American museum since the Museum of Modern Art’s 1989 exhibition that precipitated a seemingly unending Warhol mania in the art world. “I really feel that having met him, even for that short period of time, made it different for me,” she says. “It made him human.”

An Early Fascination

As a young curator, De Salvo became fascinated with the artist while digging into Dia’s huge collection of his work, which spanned little-known pieces from the 1950s to his enigmatic “Shadows” series of the late ‘70s (which are on view now in New York at the Calvin Klein Headquarters until December 15).

Based on the strength of Dia’s holdings of Warhol’s 1960s “Disasters” series, she proposed doing a show of this material in 1986. He was game. “It was kismet because he was at that time working with Basquiat and Haring and was really energized by young people,” recalls De Salvo, who thinks he appreciated her genuine interest in understanding the work.

Andy Warhol, Ethel Scull 36 Times (1963). © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York.

While she was crushed he skipped the dinner for the opening—“I got a message that he had to go to his chiropractor,” she says—Warhol became very engaged with the young curator after she proposed a second Dia show of his pre-silkscreen, hand-painted images from 1960 to 1962. She conducted two long interviews with him in which he offered new insight into how he arrived at his silkscreen paintings—once she shut up, she recalls, and stopped nervously filling in the silences. He described the influence of Ad Reinhardt, who seemed to make the same black paintings over and over that were actually very complicated underneath.

“Right there, he gets the idea of something being the same but different,” says De Salvo. “He was a sponge. He had an incredible acuity for looking.” At the Dia opening of the hand-painted works in late 1986, Warhol told De Salvo’s brother, “She did a good job,” De Salvo recalls, thinking that’s what an art teacher would have said. He gave her a little painting of a hamburger on a gold background as she was leaving the Factory after a meeting about another possible project. Warhol died unexpectedly in February 1987 after gallbladder surgery at age 58, while the Dia show was still up.

The Warhol retrospective at Tate Modern in London in 2002, curated by Donna De Salvo. Photo by Sion Touhig/Getty Images.

Separating the Myth From the Man

Over the course of her career, De Salvo has revisited Warhol every decade or two. She organized a show of Warhol’s 1950s commercial work for the Grey Art Gallery in 1989 and a traveling retrospective while she was senior curator at the Tate in London in 2002.

Having spent so much time with his work over such an extended period, she now hopes to separate the myth from the man. “To get people to actually look at what he made is not as easy as it might sound,” says De Salvo, one of the few female curators who has worked extensively on Warhol. “There are a lot of Warhol shows that get organized, some good, some opportunistic. You put Warhol in the name and people show up. In some way it muddies the waters, reinforcing old reads of Warhol.”

Left: Andy Warhol, Christine Jorgenson (1956). Right: Andy Warhol, Untitled (Hand in Pocket) (c. 1956). © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York.

Part of her take on the artist stems from a kind of identification with Warhol—the son of Czech immigrants—that she felt coming from a similar background. “My grandparents were from southern Italy and came through Ellis Island and my parents grew up in the Depression,” she says. “I think the class perspective never leaves. That’s a huge part of Warhol. As much as he’s an insider, he’s also an outsider. That’s where he could have this cold stare and voyeuristic perspective. Even his choices of things, the darkness within it, is so much influenced by the complexity of him as a gay man, as an immigrant kid, working class.”

At the Whitney, De Salvo delves deeply into Warhol’s little-seen early work from the 1950s, made after he moved from Pittsburgh to New York in 1949 and began freelancing as a commercial illustrator. “You see Warhol before Warhol, the invention of self,” she says. She juxtaposes his early assignments—including gold-leaf collages done during his two-year gig as the illustrator for the I. Miller shoe company—with his personal work, such as drawings of men’s feet, penises with bows on them, and men playing dress-up.

Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait (1964). © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York.

A Gay Icon

“Warhol was much more out than a lot of people in the 1950s,” including fellow artists Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cy Twombly, De Salvo notes. Shortly after Warhol’s death, she interviewed a lot of gay men from the advertising and fashion worlds who admired his flamboyance in that more buttoned-down age. Work with overt homoeroticism was often dismissed: When artist Philip Pearlstein, Warhol’s classmate from the Carnegie Institute of Technology, took one of his paintings of two boys kissing to Tanager Gallery in the late 1950s, it was received only with laughter.

This kind of attitude may have led Warhol to obscure such content, De Salvo posits. But that doesn’t mean it disappeared. “Embedded in so many of his selections in the 1960s is this duality,” she says. “If he chooses Marlon Brando, he’s both a female heartthrob and he’s a gay icon. Marilyn could be a drag queen in the way he articulates it.” When he made portraits based on FBI mug shots for the facade of the New York State Pavilion in the 1964 World’s Fair, he slyly tiled the series “Most Wanted Men,” in parallel with a series of screen tests called “The Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys.”

Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych (1962). © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York.

“Understanding how he pushed that envelope is an aspect of Warhol not always as explored as it could be,” says De Salvo. Included in the Whitney’s film series is intimate footage of John Giorno, the subject of Warhol’s 1963 silent film Sleep and his boyfriend at the time, washing dishes naked.

Looking Beneath the Surface

It wouldn’t be a blockbuster without Warhol’s canonical silkscreen series from the early ‘60s—including the “Disasters,” “Marilyns,” “Elvises,” “Electric Chairs”—and the Whitney will have key examples from each. But De Salvo also devotes considerable room to the work Warhol made after he was shot by the mentally ill writer Valerie Solanas and nearly died in 1968. In the 1989 MoMA show, two-thirds of the exhibition focused on work up into the 60s, according to De Salvo, who hopes to challenge many people’s perception “that after he got shot he didn’t do anything interesting.”

De Salvo argues that, in fact, he began to experiment more freely at that time. “He moves toward something that has the look of abstraction”—whether his series of “Camouflage” paintings, where the simulated landscape appropriated from military use alludes to ways of concealing and hiding, or his “Rorschachs,” which are about the problem of projection and interpretation.

Andy Warhol, Rorschach (1984). Whitney Museum of American Art. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York.

In 1978, Warhol takes on the shadow as subject matter in itself in a series of looming shapes silkscreened in different colors and sprinkled with diamond dust. “It’s still unknown what the source was,” says De Salvo. “Focusing on the shadow is the most existential, philosophical thing.”

De Salvo views Warhol’s “Last Supper” paintings, his last big series from the mid-1980s in which he appropriated Leonardo’s famous image, in the context of Warhol’s Catholic upbringing, which she shares. “Who knows how often he went to church, but it was clear he never gave up his Catholicism,” she says. “In this 1980s moment, there is a lot of loss in his life from AIDS and he’s terrified of catching it. I think he also has this worry, somewhat superstitious, about the afterlife that comes from his family background in Czechoslovakia.”

Andy Warhol, Big Electric Chair (1967–68). © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“What it comes down to is the guy was mortal and in some way there’s vulnerability within his work,” says De Salvo. “And there’s coldness within the work because there are aspects of capitalism that are cruel. There’s some human element to it that I want to return to Warhol.”

“Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again” is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York from November 12 through March 31, 2019.