The new book Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly is not a typical artist biography. It might have been had the author—poet and essayist Joshua Rivkin—been granted access to the Cy Twombly Foundation’s archives. But he wasn’t. Instead, Rivkin claims that the foundation actually wanted to inhibit his research and that, before he’d even finished the book, he began receiving emails from its attorney. It remains unclear whether the foundation simply didn’t want to cooperate or if Rivkin’s book contained inaccuracies and false testimony, as the foundation’s attorney claimed.

In Rivkin’s telling, those in Twombly’s inner circle—and particularly the artist’s longtime partner, Nicola Del Roscio—have gone to considerable lengths to ensure that certain accounts of Twombly’s life never become public. That’s where the “erasure” in Rivkin’s title comes in. To Del Roscio, these unauthorized stories are mere “gossip”; to Rivkin, they render a fuller picture of the artist’s life and work.

What seems to have sparked Del Roscio’s ire is an unlikely subject: Twombly’s occasional assistant, Butch Bryant. When Rivkin told Del Roscio that he had met Bryant in Twombly’s hometown of Lexington, Virginia, in 2012, Del Roscio was apparently “without kind words” for the man, and the foundation later provided a statement from Bryant saying that he had never said things attributed to him in the book. Rivkin believes that this is because Bryant, a “typical Rockbridge redneck,” as the man is said to have described himself, might have been perceived as a threat to Twombly’s legacy. (Disclosure: I received an early copy of the book because I was asked to provide a blurb for it.)

The cover of the book Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly (2018) by Joshua Rivkin, published this week by Melville House Books.

A Rocky History

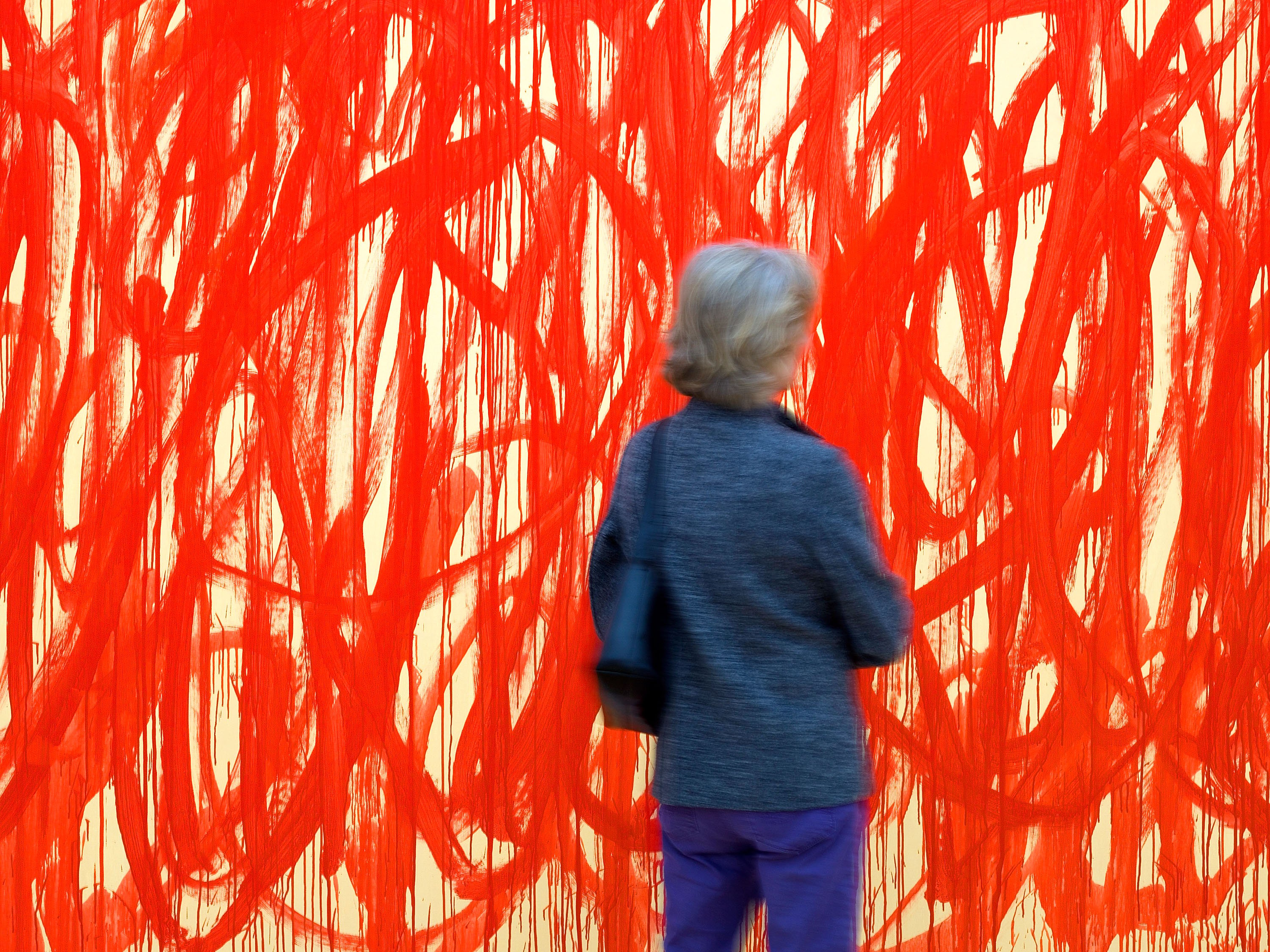

Twombly is a towering figure in 20th-century art history. His idiosyncratic practice, which combines childlike scribbles with classical references to the art and poetry of antiquity, was recently the subject of a retrospective at the Pompidou Center in Paris, while his paintings fetch as much as $70 million at auction.

The Cy Twombly Foundation was formed in 2005, and was notoriously embattled by high-profile lawsuits in 2013, two years after the artist’s death. The lawsuits included competing claims between its directors. Ralph Lerner filed a petition in Delaware court seeking the appointment of a custodian to resolve the dispute, and Del Roscio responded with a derivative lawsuit filed in the name of the foundation against another director, Thomas Saliba, alleging that he had inflated the value of the estate in order to increase his commissions as an executor, and that he had paid himself hundreds of thousands of dollars in unlawful fees. The lawsuit against Saliba was later amended to add a claim against Lerner for also taking hundreds of thousands of dollars in unlawful legal fees.

The board members settled the lawsuit and Lerner and Saliba resigned as part of the terms.

Untitled I-IX by Cy Twombly at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Museum. Photo: Giuseppe Cacace/AFP/Getty Images.

An Awkward Introduction

Although Twombly was married to a woman, many who were close to him considered Nicola Del Roscio, the author of a number of books on the artist, his true companion. He is also president of the Twombly Foundation, making his blessing essential to any Twombly researcher’s process. “Nicola is the person closest to Twombly, living or dead,” Rivkin writes. “He is the official gatekeeper.”

In several awkward encounters described in the book, Rivkin portrays Del Roscio as snobbish, intelligent, and fiercely protective of the artist’s legacy. As might be expected, their first meeting in Rome “wasn’t so much an interview of Nicola but an interview of me—where I’m from, what I’m doing here, who I’ve talked to so far. Am I someone worth talking to?” Rivkin writes.

Rivkin said that Del Roscio “deflected” each time he asked a question. “He wanted to know about the research I had already done, and more importantly, who I had talked to.”

Having recently visited Twombly’s hometown of Lexington, Rivkin listed off the names of a couple of Twombly’s friends he had met there, including Butch Bryant.

In Rivkin’s telling, Del Roscio asked to read his notes about the trip and Rivkin agreed to send him an excerpt, including a portion about his meeting with Bryant. “I thought these pages, early versions of a book still in flux, would show Nicola my deep love for Twombly’s work and the kind of research I’d started in the United States,” he writes.

When Rivkin sent the pages, he attached a note saying that he normally wouldn’t send unfinished writing to a source, but was making an exception for Del Roscio as a “show of good faith and the hope that you’ll be willing to be interviewed.”

He was wrong.

“You’ve Written Lies”

“‘I really didn’t like what you wrote,'” Del Roscio reportedly told him when the writer met him in Gaeta for what he thought would be an interview.

“‘Lies,'” he said, in Rivkin’s telling. “‘You’ve written lies.'” Del Roscio specifically cited a passage about Bryant, who Rivkin describes as Twombly’s assistant for nearly 10 years. Bryant apparently managed the artist’s schedule, his checkbook, and drove him around. He was “Cy’s right-hand man in Lexington,” Rivkin quotes one obituary as saying.

As evidence that Rivkin’s book was unreliable, Del Roscio pointed to a portion of the draft that discussed several Twombly sculptures. Del Roscio said that the artist had given Bryant these three sculptures as a gift. The draft told a different story: that Bryant allegedly cast some doubt on whether this gift actually occurred. The details of this incident are largely absent in the final book, aside from Rivkin noting that Del Roscio had pointed to it as an inaccuracy. (artnet News called Bryant for comment but did not get a reply.)

Untitled (Bacchus 1st Version V) (2004) by Cy Twombly during a press preview at Sotheby’s. Photo: Ben Stansall/AFP/Getty Images.

Bryant was also Twombly’s studio assistant. “‘I cut canvases, I hung canvases on the wall, I done all the backdrop painting,'” Rivkin quotes Bryant as saying, “‘and basically, when he walked into the studio, he was ready to do his loops, curls, marks, or whatever he wanted to do. The same thing with sculptures. Sometimes we’d come in here and work on paintings. Sometimes we’d work on sculptures.'” In Rivkin’s account, Bryant quoted Twombly as once telling him, “‘His paintings and everything would not have excelled if it hadn’t been for me.'”

Rivkin speculates that this may have been part of what seemed to gnaw at Del Roscio: that a mere employee—an uneducated “redneck,” no less—would have the audacity to claim that he mattered to Twombly, and might even have contributed to some of his greatness.

But elitism may not have been the only factor allegedly driving Del Roscio’s objections to Bryant’s account, according to Rivkin. It’s also possible he was concerned that Bryant’s comments might also raise new questions about the mythology surrounding Twombly’s process.

Rivkin doesn’t go so far as to suggest that Twombly’s work is inauthentic merely because he had an assistant. The artist’s vision was “too singular” to have been “phoned in,” he writes. But in his opinion, “Butch’s very presence runs counter to a mythology in which Twombly worked only alone—or alongside Nicola.”

He notes that critic Arthur Danto believed Twombly worked alone, “[a]part from Nicola,” and that Twombly himself said in 2004 that he never had an assistant.

The Source Recants?

On their final meeting, Del Roscio told Rivkin that he worried the author was writing “a book of gossip.” Rivkin claims that Del Roscio offered to work with him only if he allowed him to review and “correct” the writing. He mentioned, in particular, that Rivkin needed to change what he had written about Butch Bryant.

From left: Cy Twombly: Fifty Days at Iliam; Mary Jacobus, Reading Cy Twombly: Poetry in Paint; and Sally Mann, Remembered Light: Cy Twombly in Lexington. Courtesy of Amazon.

Reached by artnet News, the foundation’s attorney declined to comment on Rivkin’s book, but pointed out the numerous other scholarly projects that it has supported either financially or through access to Twombly’s archives, including the forthcoming book Cy Twombly: Fifty Days at Iliam (Yale University Press), Mary Jacobus’s Reading Cy Twombly: Poetry in Paint (Princeton University Press), a catalogue for the recent retrospective at the Pompidou, and Sally Mann’s photographic memoir Remembered Light: Cy Twombly in Lexington. The attorney also added that the foundation did not supervise the content of these books or require editorial approval, nor has it ever charged for image rights.

About five months after his final meeting with Del Roscio, Rivkin received a note from him: He had decided that Rivkin’s writing wouldn’t do Twombly “justice.” He also said the draft he had seen contained inaccuracies, such as the “fantasy by Butch, a close relationship that never existed.”

Then came another message, this time cc’ing the foundation’s secretary and attorney. Del Roscio said he had contacted Bryant, who told him that he had never spoken to Rivkin.

Rivkin did not record his conversations with Bryant, but claims that he took notes, kept cell records of their calls, and had accounts from others who were present when he met Bryant. He wrote back a defense of his reporting:

To be clear, I met Butch on two occasions in Lexington. My reporting of his comments is accurate. His point of view and memories are important, even they [sic] are partial and even if he leaves some things out. What he leaves out is, in a way, just as important as what he includes, and any careful reader will see this.

A few days later, another letter came from the foundation’s lawyer. It included a statement from Bryant claiming he had never met Rivkin, but that if he did, which he couldn’t recall, he never said any of the things Rivkin reported. (The lawyer confirmed to artnet News that he sent Rivkin a statement from Bryant.)

In response, an attorney wrote a letter on Rivkin’s behalf reasserting that the author was telling the truth about Bryant. Rivkin never responded again.

The book is out this week—with at least some of Bryant’s account intact. “To have continued to write and research and publish after the initial push-back was, and is, perhaps an act of foolishness,” the author writes. “But what else, in the aftermath of confrontation, was there to do?”

UPDATE, October 24: This article has been amended to clarify the sequence of events in the Cy Twombly Foundation’s 2013 legal disputes.