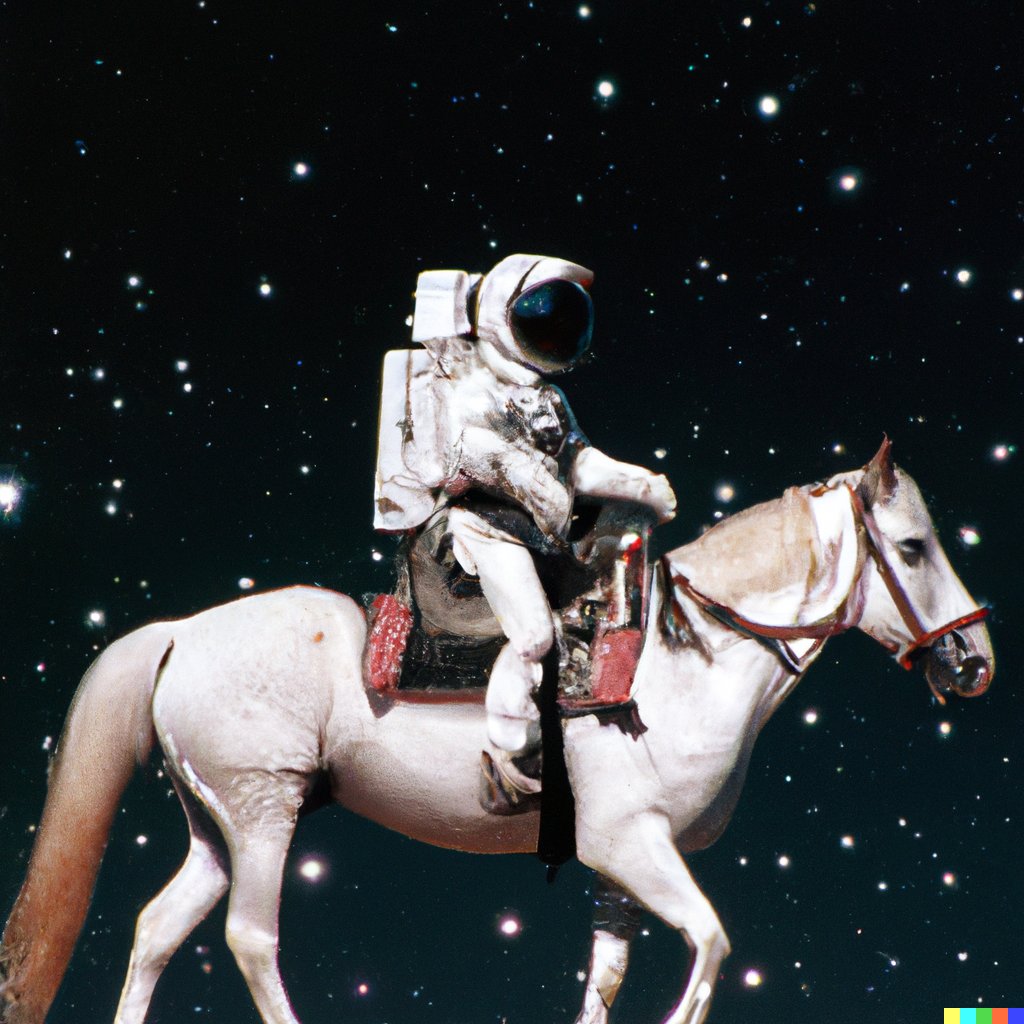

An avocado armchair. An astronaut riding a horse on the moon. The Girl with a Pearl Earring… but with a different girl.

These are some of the images produced by DALL-E, a new AI system that has the ability to generate hyper-imaginative—and hyper-realistic—pictures with the click of a button. It just may transform the way contemporary art is made, for better or for worse.

With a name that nods both to the 2008 animated film WALL-E and the surrealist master Salvador Dalí, DALL-E is the product of OpenAI, a leading artificial intelligence company based in San Francisco. A neural network, the program learns to interpret and recreate visual information by analyzing millions of pictures and other pieces of data.

The resulting pictures aren’t perfect—a close inspection will often reveal glitchy oddities, as if made by a painter nodding off at the easel. But they’re close enough to pass on first glance.

“One way you can think about this neural network is transcendent beauty as a service,” Ilya Sutskever, the cofounder of and chief scientist at OpenAI, told the MIT Technology Review. “Every now and then it generates something that just makes me gasp.”

And the technology’s only getting better.

The second iteration of DALL-E was unveiled by OpenAI this month, and it represents some significant advancements for the technology.

Apart from producing images faster and in higher resolution than with the first version (released in January 2021), the system now “understands” the relationship between images and the words we use to describe them—and it can take either as an input to create something entirely new.

The program, for example, can generate an original image from just a few words (“A teddy bear on a skateboard in Times Square“), or create variations on existing pictures or paintings (think Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, but set elsewhere and populated with new characters).

With this power comes new opportunities for invention—but also significant potential for misuse.

DALL-E isn’t available to the public yet, but if it was, users could theoretically use it to churn out deep fake images, or launch disinformation campaigns. (Neural networks also have built-in biases, as Trevor Paglen and Kate Crawford’s widely-influential ImageNet Roulette project revealed.)

As a safeguard, OpenAI watermarks all DALL-E images, and the program prevents its users from creating pictures deemed to be violent, pornographic, or political.

“This is not a product,” Mira Murati, OpenAI’s head of research, recently told the New York Times. “The idea is [to] understand capabilities and limitations and give us the opportunity to build in mitigation.”

As far as the world of contemporary art is concerned, DALL-E and other programs like it could have big implications. There’s already a burgeoning market for AI-generated art: the first AI-generated portrait, which was far less sophisticated than DALL-E’s creations, sold for a staggering $432,500 at Christie’s in 2018.

For now, OpenAI is testing the program with small, controlled groups of users, selected from a waitlist.