I traveled to West Texas to see an expansive sky, unfettered by the dense light pollution of New York City. I wanted to experience the desert landscape as sublime and profoundly revelatory, as the artist Donald Judd had in the 1970s when he decided to move to Marfa.

Since then, a lot has happened in the small Texas town. The artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset installed a faux Prada shop 26 miles northwest of Marfa, along the I-90, with shoes and handbags from the fall 2005 collection. Beyoncé visited, and ate tacos at a food truck called Food Shark. And most recently, Jill Soloway and her crew wrapped up filming an adaptation of Chris Kraus’s acclaimed book I Love Dick for Amazon.

Much of this hype can be traced back to minimalist heavyweight Donald Judd, who founded the Chinati Foundation in Marfa in 1986, and set out to support a group of (mostly male) artists making work on their own terms. Sadly, the lineup 30 years later still skews white and male, despite the Foundation’s “radical” mission, but the works themselves are sights to behold.

Guests gathered on Saturday, July 23, for a communal barbeque dinner at Chinati’s Arena to celebrate the opening of Robert Irwin’s installation untitled (from dawn to dusk). Among those in attendance were the poet Eileen Myles, artist Larry Bell, and Judd’s two children, Flavin and Rainer. At some point, I slipped out to catch the sunset, and was not alone. Event attendees ventured over one block to see the newly appointed building at dusk.

Robert Irwin, in progress. Photo Courtesy of the Chinati Foundation.

In Marfa, the sunset is flecked with rose and permeated by azure tones; after dark, a series of piercingly bright stars come into view. (In New York I experience the sunset as a blinding yellow light that cuts across my computer screen.) To say the experiences were different is a laughable understatement.

In a 16-year span, a committed crew transformed the four-acre site—formerly a hospital building on the decommissioned military base of Fort D.A. Russell—into an emotionally resonant monument to light and space. To preserve the architectural integrity of the site and make a gestural nod to its history, Irwin maintained the area’s specific slope: as visitors walk south down the halls, the land subtly curves higher to meet the eye.

Chinati’s director Jenny Moore told me that she tends to walk through the building from dark to light sides, from a “place of compression and intimacy” into a more open space. The mutability of natural light allows for profound perceptual shifts. I visited the building three times in two days, and with each visit, I was thrilled to discover a distinct, new visual effect.

Robert Irwin, Artwork Exterior Before Completion. © 2016 Philipp Scholz Rittermann. Courtesy of the Chinati Foundation.

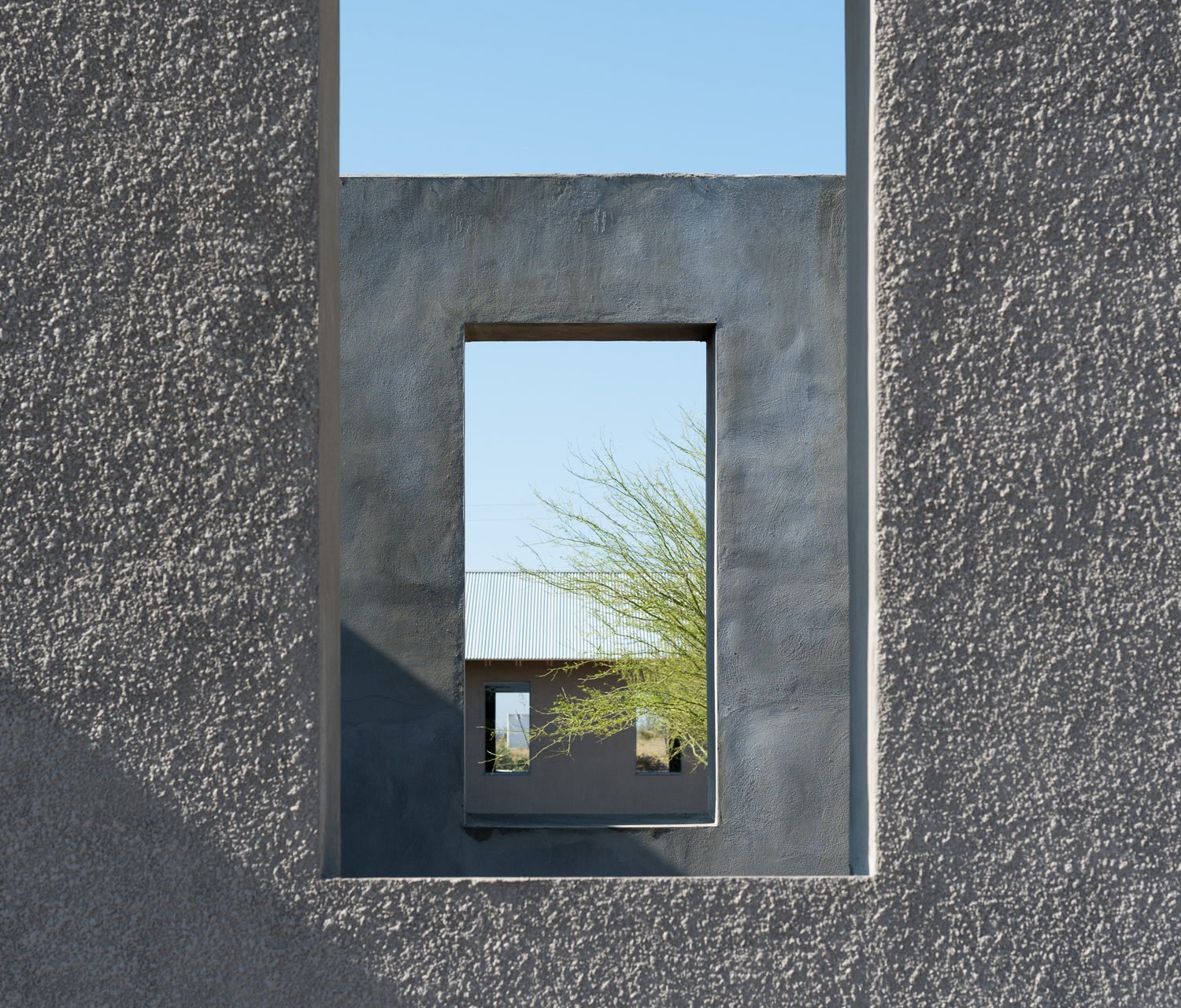

Irwin’s U-shaped building is divided into black-and-white hallways and lined with translucent scrims that filter the incoming light. High-polished cement floors and a neat succession of eye-level windows enable rectangular light shadows to materialize throughout the space. In the unfurnished interior, sound travels quickly and ricochets with intensity, which seems incongruous to the otherwise enveloping calm of the space.

Originally, Irwin wanted to integrate colored glass panels into the hallways, but as the work evolved, he removed elements that felt superficial, such as color, arriving at a pared-down design; Moore referred to this as “the essence of [the] site.” The final configuration frames the small strip of surrounding land and vast, expansive sky like a Dutch landscape painting.

In sharp contrast to the work’s austere, monochromatic interior, the inner courtyard is vibrant—teeming with Blue Grama grass and Palo Verde trees. A collection of textured basalt columns quarried in Washington state punctuate the space, and a path surrounding it encourages circumambulation—echoing the way one travels through the work’s interior.

Ingólfur Arnarsson, Untitled Works (1991-1992). Courtesy of the Chinati Foundation. © Ingólfur Arnarsson, Reykjavik.

Up to this point, Irwin’s most well-known installations have largely been temporary works, like Excursus: Homage to the Square3 at Dia: Chelsea and untitled (four walls), which was installed at Chinati in 2006. This work’s permanent nature is therefore quite significant. The artist’s sensitivity to the surrounding landscape, interest in shifting spatial relationships, and treatment of light as material align squarely with the minimalist, light and space artists who have permanent installations at Chinati. (Works by Dan Flavin, John Chamberlain, and Carl Andre also make appearances.)

The installation’s sequence of windows and corresponding shadows resonates with the Icelandic artist Ingólfur Arnarsson’s untitled works (1991-2), an installation that includes 36 graphite drawings on paper mounted diametrically opposite a row of windows. Irwin’s work also reflects Donald Judd’s iconic 100 untitled works in mill aluminum (1982-86), in which two of the most significant elements are the illusory potential of light, and the interplay between exterior and interior landscapes.

To take in the sky, in all its vastness—which is to say, to commune with nature—one must leave New York. Irwin’s newly-minted installation and its dynamic, surrounding environment provide an extraordinary reason to do so.