How’s this for a monument proposal: a gigantic bowling ball rolling down New York’s Park Avenue, chasing Billionaires’ Row residents like the boulder in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

This is one of two Proposed Colossal Monuments (1966–67) cooked up by Claes Oldenburg that were set to be included in an exhibition planned by the humanist art collectors Dominique and John de Menil in the early ‘70s. Their vision was to bring together a group of postwar artists making public art that was, according to the de Menils’ notes from the time, “neither architecture nor sculpture.”

But the show, called “Dream Monuments,” never saw the light of day.

At least, until now. On view through September 19 at the Menil Collection’s Drawing Institute in Houston, the exhibition “Dream Monuments: Drawing in the 1960s and 1970s” revisits and reimagines the de Menils’ plan. Included are drawings—and a few small models—of would-be monuments from 21 different mid-century artists, such as Beverly Buchanan, Michael Heizer, and Robert Rauschenberg.

Claes Oldenburg, Proposed Colossal Monument for Park Avenue, New York – Bowling Balls (1967). Courtesy of the Menil Drawing Institute.

Almost all of these works were never actually realized. Many of them, like Oldenburg’s bowling ball, simply couldn’t be, defying physics or financial realities. Walter De Maria wanted to build two parallel mile-long walls in the desert. (He couldn’t raise the funds so he compromised by drawing lines in the sand.) Christo sought to erect an Egyptian funerary tomb—called a mastaba—by stacking no fewer than one million oil drums alongside a Texas highway. (Never one to give up, the late artist went on to realize a pared-down version in London in 2018.)

That’s why it’s helpful to think of “Dream Monuments” as a drawing show—not a sculptural one. While the exhibition’s curators, Erica DiBenedetto and Kelly Montana, supplemented the lineup with additional works from artists active in the 1960s and ’70s, they retained the de Menils’ original title for this reason.

“To my mind, ‘Dream Monuments’ is a term that evokes something that is specifically about drawing. It’s not about, in the end, building something for the outside world,” DiBenedetto told Artnet News. Instead, the term is about “an idea or a concept and how that’s explored through drawing.”

Here, added Montana, “the page is the space for the possible and the impossible.”

Christo, One Million Stacked Oil Drums, Project for Houston, Galveston Area (1970). Courtesy of the Menil Drawing Institute.

The current iteration of the show was finalized during the middle of 2020, just as a dialectic about the role and relevance of monuments once again bubbled to the top of public discourse. It’s tempting to view the exhibition through that aperture—to look back and wonder if these artists, bound by the constraints of imagination rather than reality, can offer us the tools to reimagine a convention so desperately in need of it.

But you won’t find a panacea here. “You can’t map the political and social concerns of today onto these works,” Montana said. “It’s not an easy fit; I don’t think there’s a way to draw a straight line.”

The monuments debate of today, mired as it is in issues of colonialism, slavery, and race, is very different than the one being had by Agnes Denes, Dennis Oppenheim, and others in the Menil show. Only in a few instances do these artists’ proposals come with an expressly political agenda; their concerns are largely more formal, more conceptual. (It’s also notable—and perhaps revealing—that the vast majority of the artists included in the exhibition are white.)

Nevertheless, the questions these artists asked do resonate today: What is a monument? Is its function still relevant? Why do they look the way they look?

Robert Smithson, Cambrian Map of Sulfur and Tar (1969). Courtesy of the Menil Drawing Institute.

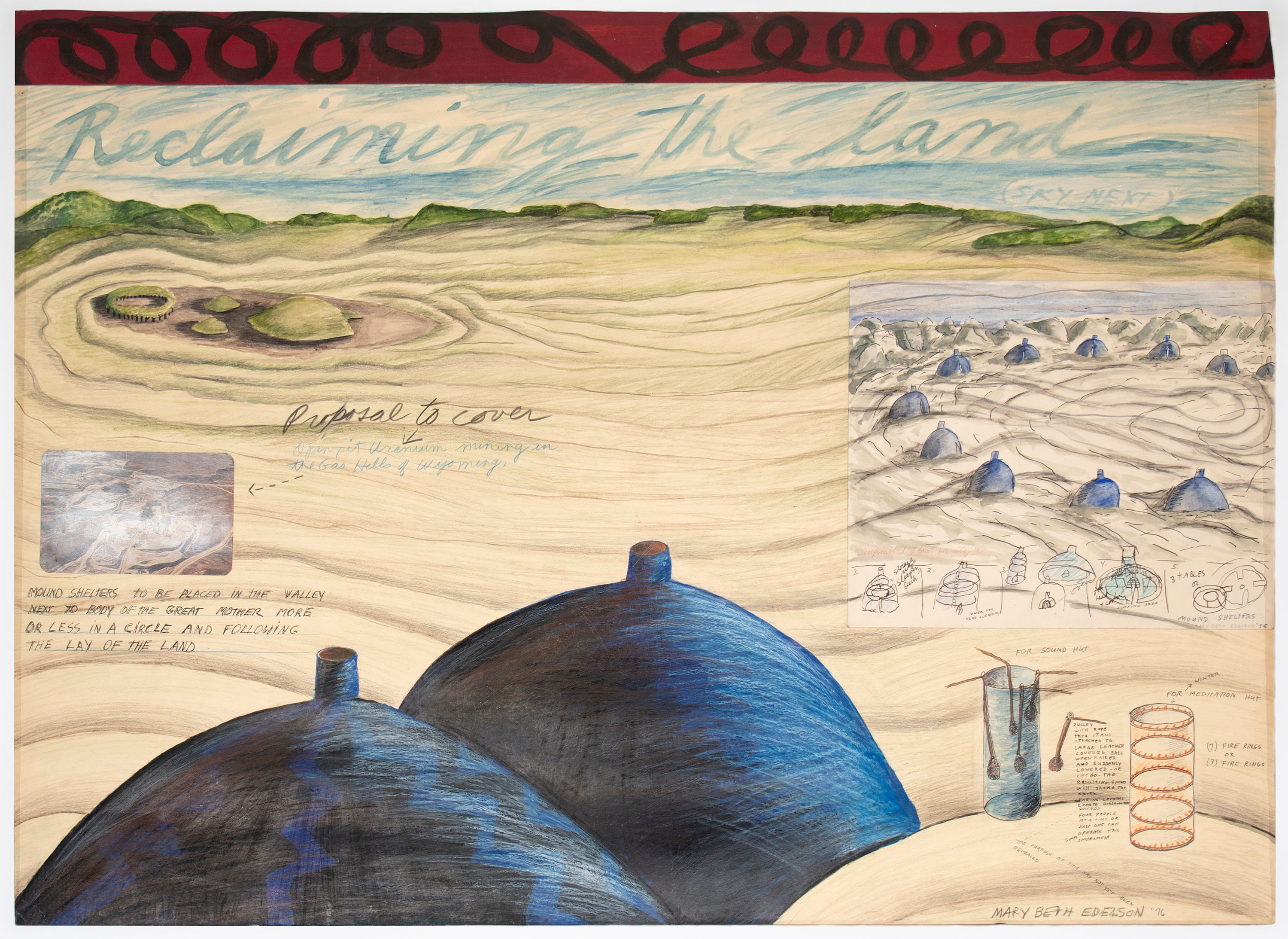

A drawing by Robert Smithson, for instance, proposes dumping heaps of unprocessed sulfur into enormous pools of tar, putting in motion a process that, he believed, would map the movement of the Earth’s land and water 500 million years ago. Similarly, Mary Beth Edelson sought to fill uranium mines in Wyoming with mounds of soil that would both recall ancient sacred sites and literally embody the female form.

These examples don’t look anything like the monuments you or I know. But as a thought exercise, Montana and DiBenedetto point out, they may prove useful insofar as they instruct us to think through the elements of modern-day monuments that have become so conventionalized we forget to question them in the first place.

Or, to put an even finer point on it: through rethinking the form of monuments, we may learn to rethink other aspects of them, too.

“Dream Monuments: Drawing in the 1960s and 1970s” is on view at the Menil Drawing Institute in Houston, Texas, through September 19.