The issue of Nazi-looted artworks and ongoing restitution cases has been making headlines for decades, reaching a new height of interest since the Gurlitt trove was discovered in 2012 in the art hoarder’s Munich apartment.

Since then, Nazi-looted artworks—Gurlitt’s and others’—have very publicly been moving across private hands, museum collections, and auction houses.

Last month, for instance, Max Liebermann’s Two Riders on a Beach sold at Sotheby’s London for £1.9 million (almost $3 million), shortly after its return to the heirs of David Friedmann, who saw his treasured painting confiscated by the Nazis.

But for the London Old Masters dealer Julian Agnew—the previous owner of Agnew’s gallery, which switched hands last year thanks to a timely acquisition by a group of investors—the auction of restituted artworks is a trend that won’t stop any time soon.

Max Liebermann, Two Riders on a Beach (1901).

Photo: via Wikimedia Commons.

In a letter sent to the Financial Times, self-explanatorily titled “The auction of nearly all restituted works of art is inevitable,” Agnew likened the restitution of Nazi loot to “ambulance chasing,” an expression used for lawyers that search for new clients at disaster sites.

In the letter, Agnew writes:

Since 1990 […] a whole trade of researchers, aided by lawyers, has grown up which seeks to notify the descendants of Nazi-era owners and put forward restitution claims. The basis of the deal with the claimant is that the researchers and lawyers take a very considerable percentage of the sale proceeds of restituted items. This means that their auction is inevitable. This is not an attractive side of the art market, being comparatively close to ambulance chasing.

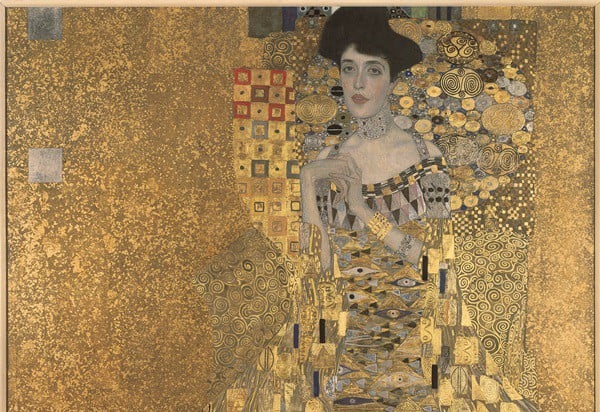

Agnew also appears wary of the sale of Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907) in 2006 for a whopping $135 million—not in auction but accomplished with the help of Christie’s: “The net result of this story is that large sums of money have changed hands and the ownership of the painting has been transferred from the Viennese museum, in which it could be argued it would most appropriately be shown, to that of a collector who for the time being is showing it to the public in his privately owned museum in New York.”

In the letter, Agnew also raised the banner of present-day owners of looted artworks, usually acquired in good faith, who find themselves deprived of their precious items.

Julian and Victoria Agnew.

“Is it not time to consider putting a time limitation on such claims?” he writes. “The Monuments Men did a very good job in restituting works of art in the three years after the end of the war.”

“If these claims are allowed to go on forever, it will soon be as impossible to separate right from wrong as it would be to reopen claims from the last period in which great quantities of art were moved around Europe in doubtful circumstances, the Napoleonic wars,” he warned.

Meanwhile, from a very contrasting vantage point, Peter J. Boren, the descendant of David Friedmann, explained in an article for Yahoo News what the restitution of Two Riders on a Beach meant for him:

Two Riders has meant so much more to me than simply its sale. It allowed me to reclaim part of my family’s history stolen by the Nazis. I learned things that I had never known including more about my father’s courage to succeed in the face of all odds. I now understand to the extent possible, what it meant to be a Jew in Nazi Germany. We have only begun, but will continue to search for other stolen David Friedmann paintings, however long it takes.

Christopher Marinello posing with a restituted Matisse.

Photo: Courtesy of The Art Recovery Group.

NOTE: Anthony Crichton-Stuart, director of Thomas Agnew & Sons Ltd, sent a letter to artnet News stating: “The owner and directors of Agnew’s note the comments of Julian Agnew, a former director of this firm, in his letter to the Financial Times of 3rd July, entitled The auction of nearly all restituted works of art is inevitable, are neither the views nor opinions of the present management of ownership of Thomas Agnew & Sons Ltd. Mr. Julian Agnew was expressing his own privately held views on the matter.”