Big changes are coming to the galleries of the Delaware Art Museum, and visitors are already getting a sneak peek at what’s in store.

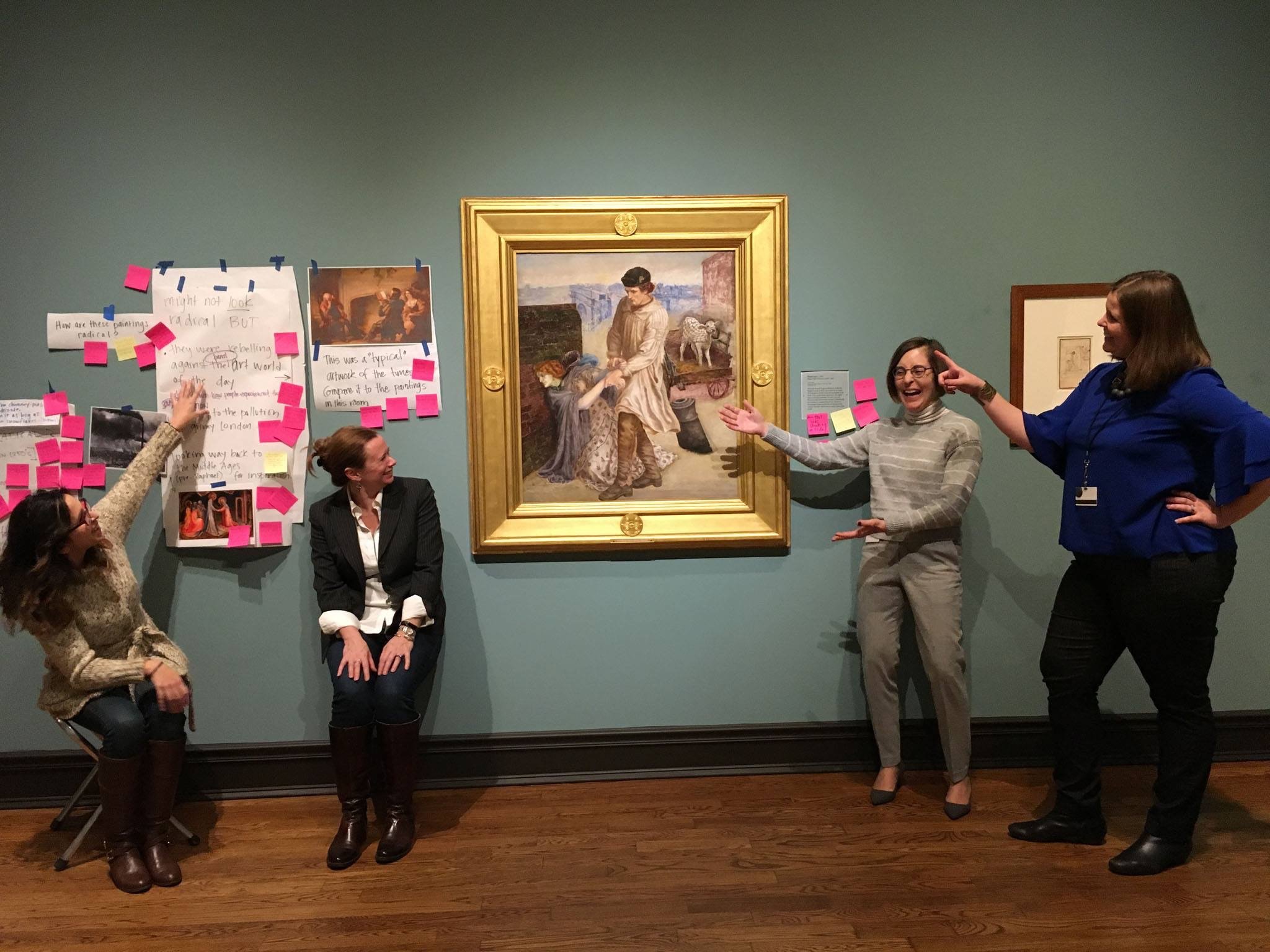

As the museum plans for an upcoming reinstallation of much of its permanent collection, the curatorial and educational staff are turning to the local community for input. This process has involved asking the public to weigh in on temporary, handwritten wall texts—including Post-It notes!—exploring alternative ways the institution might talk about its American and Pre-Raphaelite art collections.

“We’ve been on a journey as an institution internally, working on addressing some of our bias, whether it’s on staff or in programming or in the galleries, which is one area where we had identified that there were stories missing,” Saralyn Rosenfield, the museum’s director of learning and engagement, told artnet News. “What can we be retelling in a more inclusive way that is more relevant to and representative of our local community?”

To help add to the narrative, the museum has held salons to ask members of the public and museum stakeholders and partners what, exactly, they thought about the museum’s first floor galleries. Museum staff listened carefully and responded, sometimes researching very specific questions about the background of artists or works in the collection.

“Our new strategic direction is to be more outward facing, more community engaged, and more involved with our visitors and our target audiences,” explained Heather Campbell Coyle, the museum’s chief curator. “We’re trying to see what they get out of what’s there now, and what they’d like to see added.”

The initial spark for the overhaul came from the Pre-Raphaelite gallery, which hadn’t been reinstalled since 2007, despite numerous new acquisitions, including a considerable number by female artists. “And then we thought, wouldn’t it be great if we could reinstall all these galleries?”, Coyle added. “They all need some updates.”

With that mission in mind, Coyle and Rosenfeld attended the 2018 convening of MASS Action (the Museum as Site for Social Action), an initiative founded by the Minneapolis Institute of Art for museum professionals promoting equity and inclusion in art museums. They also followed the model of Kathleen McLean’s Independent Exhibitions, a museum consulting firm, in introducing prototyping, which allows the public to give feedback about a new exhibition direction before it is permanently implemented.

Feedback about gallery prototyping from visitors to the Delaware Museum of Art. Photo courtesy of the Delaware Museum of Art.

Four salons have been held to date, each one about a different area of the collection. After each one, the curatorial staff has set about reinterpreting the galleries, handwriting new wall text and considering new groupings of work based on the feedback they’ve received. In some cases, they’ve hung up color photocopies of a new work that might be added to the display.

For the American art galleries, preliminary wall text has addressed the issue of slavery, acknowledging Delaware’s history as a slave-owning state. In its display of American landscape paintings, the museum considers the myth of the Native American as a “vanishing race,” compared to the brutal reality of forced Indian migrations.

In a common trope in American landscape paintings, “peaceful Native Americans and open spaces imply unlimited opportunities for expansion. What isn’t shown is the violence that emptied these spaces,” reads one text.

Alvan Fisher, Remnant of the Tribe Leaving the Hunting Ground of Their Fathers (circa 1845). Courtesy of the Delaware Museum of Art, gift of the Friends of Art, 1971.

In the Pre-Raphaelite galleries, the curators are hoping to make these British painters relatable to a contemporary audience. The institution’s Bancroft collection is the largest Pre-Raphaelite collection outside the UK.

“A lot of that is about how artists rebel against their times and the art world of that day,” said Amelia Wiggins, the museum’s manager of gallery learning and interpretation, pointing to Simeon Solomon, who as a gay Jewish man, was doubly an outsider in Victorian England. They focus on two of his paintings featuring a model of Jamaican descent.

The reinstallation will also reconsider the American illustration works and paintings from the Ashcan School, especially John Sloan. Visitors are encouraged to share their reactions, offering feedback on the new ways the museum is talking about and considering its collection.

Simeon Solomon, The Mother of Moses (1860). Courtesy of the Delaware Museum of Art, bequest of Robert Louis Isaacson, 1999.

The Delaware Art Museum’s prototyping is taking place on a rolling basis, in each gallery for a week or two at a time. The actual reinstallation will take place one gallery at a time beginning in early 2020. The goal is to be done by next August.

“It was not an easy decision to do this in the galleries,” admitted Coyle. “I do tend to want things to be very tidy. But what we’re learning from it is incredibly valuable. The way that audiences are reacting to it, feeling included in the process, is great.”