In her Christmas 1977 newsletter, Diana Zlotnick took the Los Angeles Times to task.

A devoted collector, Zlotnick had also become a chronicler of the local art scene through her monthly Newsletter on the Arts. Four artists she admired—Gloria Kisch, George Miller, Tony DeLap, and Bruce Nauman—had all been “unfavorably reviewed by the Los Angeles Times,” she wrote.

The stakes were high, according to Zlotnick. “When these fine artists are panned, their limited Los Angeles audience is greatly reduced and there are mass migrations to seek the greener pastures offered by New York,” she wrote. “Talent leaves because there is a lack of insight and leadership from local art critics in their writing.”

Zlotnick had articulated such opinions—about L.A.’s failure to do its own talent justice—before. But what she did even better was close looking and so, after offering her sweeping claims, she turned to a point-by-point refutation of recent reviews. Critic William Wilson had, she wrote, mischaracterized and then dismissed Kisch as an insignificant minimalist, when, in Zlotnick’s view, she used a minimalist vocabulary to convey “her own personalized message” and create “a sense of electric isolation”—something any critic who deigned to spend time with the work would surely perceive.

Diana Zlotnick. Photo: Marianne Shirley

Zlotnick would remain an avid connoisseur for the rest of her life, and continue to publish her newsletter, albeit more sporadically, into the 2010s. She often used it to fiercely defend the artists she loved—and it ultimately made her a local celebrity. Yet when she died in the summer of 2021, just shy of her 93rd birthday, there were no obituaries in major papers. It wasn’t until a large portion of her art went up for sale at Los Angeles Modern Auctions in May 2022 that the memory of her influence again made ripples.

“She was a very interesting person because it was a genuine interest and love of art,” said artist Raymond Pettibon, whose work Zlotnick began collecting in the mid-1980s, before many others had heard of him. “I have never met anyone like her,” said artist Phyllis Green, whose work Zlotnick championed from the late 1970s on. “She was a true original.”

An Underappreciated Tastemaker

Zlotnick’s love affair with what she called “California Avant-Garde Contemporary Art” started in 1954 by accident. She was, as a 1973 Times profile put it, a 28-year-old “blond young newlywed” with “all that time, no money, and a good mind” when she and her husband Harry Zlotnick, a veterinarian-in-training, went joyriding around the Inland Empire. They ended up at Pomona College.

There, at the school’s art center, they encountered a wall-length ceramic installation by John Mason. Zlotnick found in the work “a world I had never seen before,” as she later wrote in her newsletter. “I wanted to have more of that kind of refreshing experience.”

Zlotnick lived surrounded by the art she began amassing in 1959, and often hosted small exhibitions in her home. She taught seminars on collecting at local universities (she joked that her USC class, “Understanding and Collecting Art Through Direct Experience,” should actually be called “Collecting Art on Minimal Funds,” because that was her true forte). Her collection was the subject of multiple exhibitions and featured in multiple Los Angeles Times profiles.

An installation at Zlotnick’s home. Photo: Ceramics in Zlotnick’s collection. Photo: Marianne Shirley.

Because her newsletter—which reached at least 4,000 readers monthly—has never been digitized or compiled in full, Zlotnick’s influence is in danger of being lost to history. But for many who interacted with her over her more than six-decade collecting career, she is an inspiration. Dealers Adam Moskowitz and Meredith Bayse, who met Zlotnick in 2016 at their Hollywood gallery, Moskowitz Bayse, often wonder whether it’s possible to follow her example and make collecting accessible in an era with far more economic stratification than Zlotnick’s day.

“We talk a lot about younger collectors and getting them inspired to live in the art world and to be a patron,” Moskowitz said. “But the truth of the matter is, that to a certain degree, being the wife of a veterinarian and using the money that your husband makes on the side as your art fund, that’s just not feasible anymore.”

An Advocate for L.A. Art

Zlotnick’s collection became a highly personal, but expansive, capsule of a certain moment in Los Angeles art history. It spanned California assemblage, Light and Space, the Beats, West Coast pop, and a particular, sensual brand of Los Angeles conceptualism. The way she installed these works, with no hierarchy and sometimes stacked on top of one another, reflected the way these movements actually formed and functioned.

Zlotnick bought her first artwork, by John Altoon, directly from his studio on a monthly payment plan. She became notorious for them, since she only had a modest income from her husband’s veterinary business and occasional substitute teaching. “She would give you $50, and then $50 the next month, and $50 the next month,” Green said. “And she would pay up.”

She became one of Daniel LaRue Johnson’s first collectors after cornering him on La Cienega’s gallery row and asking to see the portfolio he carried under his arm. One early purchase—Johnson’s dark assemblage of a baby doll face peeking out of a hole in a wooden box—featured in the Hammer’s celebrated exhibition “Now Dig This!: Art and Black Los Angeles 1969–1980.”

An installation Zlotnick created in her upstairs office in 2012, which included work by Phyllis Green. Tony DeLap, and Harold Finster.

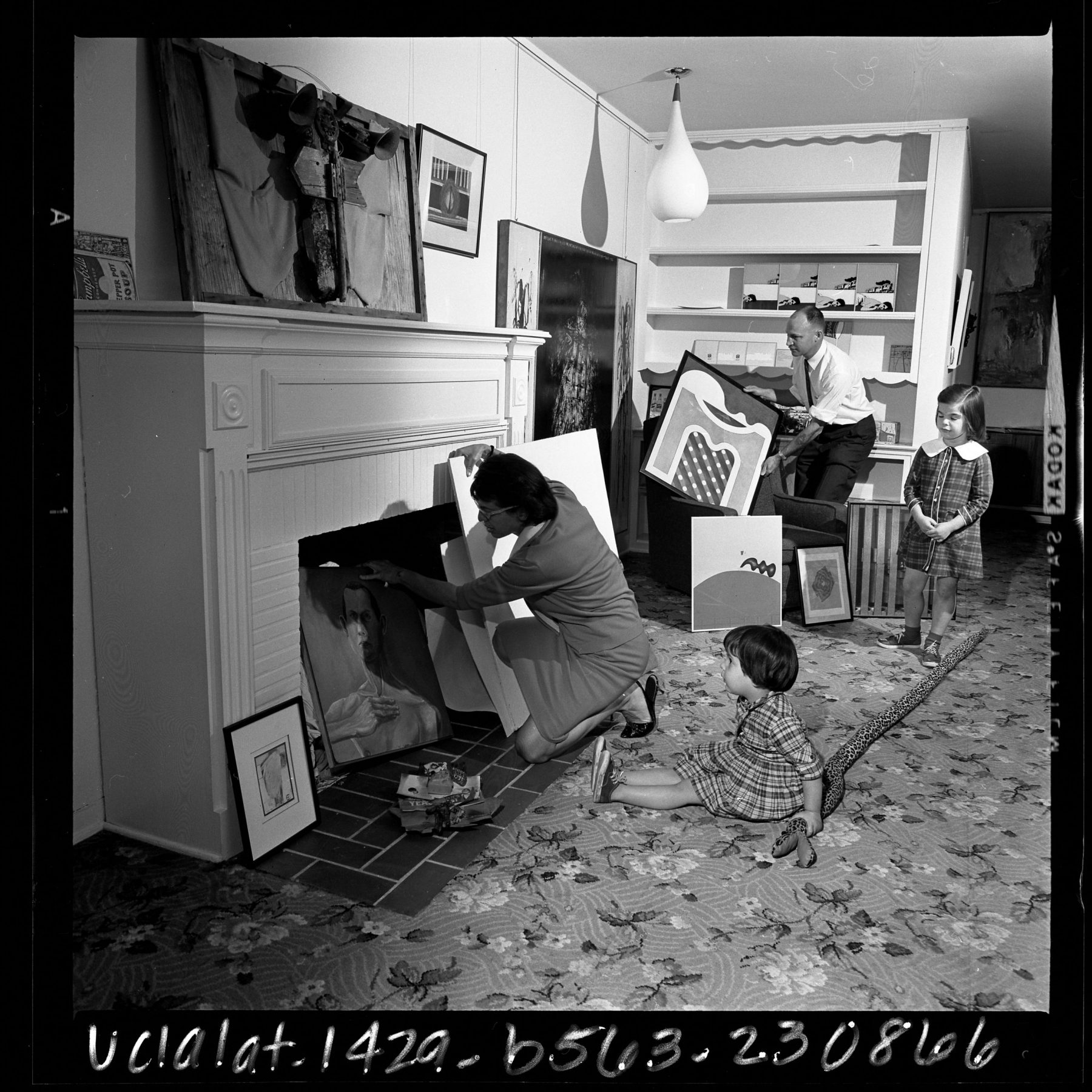

By 1965, she had two young daughters and 150 artworks, all on view in the family’s 1,500-square-foot North Hollywood house. They kept art in the fireplace and in the garage. According to a 1965 Times article, a sculptural landscape by Lyn Foulkes hung so low over the Zlotnicks’ bed that they kept their pillows tucked between the mattress and the wall, rather than resting on top of the sheets. (Harry Zlotnick died in 2000.)

When they moved from North Hollywood to the Studio City split-level where Zlotnick would spend the rest of her life, there was a little more space—but not much. Her daughters, Bonnie and Marianne, learned to live and play alongside the collection. Zlotnick thought it was good for them.

“It isn’t just a question of their seeing that a mother can do more than simply stay home and run a trim house and bake cupcakes for the PTA,” she told the Times. “They’ve discovered the realities of the creative life, that sometimes even adult artists can’t pay the rent, and people who care about the thing they have to give the external world—whether it’s romantic lyricism or abstract sociological impact—someone has to help them get the rent, keep them going.”

Marianne Shirley remembers spending Sunday afternoons going on studio visits with her mother, and artists coming and going from the family home throughout her childhood. “The [neighbor] kids called it the hippie house, which was ridiculous. My parents weren’t hippies by any means, but you know, all the artists were probably a good 10 years younger.”

The Birth of a Newsletter

Zlotnick sold key works in her collection, which included Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha and Ed Kienholz, for the first time in 1971 to fund her Newsletter on the Arts. She would say she started the newsletter out of necessity. “My phone bill was outrageous from talking with my friends about art,” she told the Times in 1973. “I would call them as soon as something new came up about an artist or his work. So I decided to put out the newsletter as a substitute for the phone calls.”

At first, the newsletters were listings of exhibitions and events with pithy commentary by Zlotnick with a few social items mixed in (“Channa Davis, Jim Horowitz, married,” “Holly Woodlawn is in a non-Warhol film,” “Yvonne Rainer wintering in Los Angeles”). Soon, she began inserting items akin to Craigslist missed connections, trying to conjure what she wanted into the world: “Someone should write an article on Edie Danieli’s career, as she intuitively understood what being a woman artist was all about long ago,” she wrote in 1972. Or, more pithily, in 1973: “Walter Hopps, where are you? Lynn Foulkes, what are you doing?”

Zlotnick’s collection on view at Los Angeles Modern Auctions. Photo: Los Angeles Modern Auctions.

Sometimes, Zlotnick would ask big questions, and just leave them there as line items: “Is innovation in art necessary?” She would also post personal ads for artists: “George Herms: Needs a car. Will exchange art works for dependable wheels.” The newsletter was a resource and a cheerleader, as well as a place for Zlotnick’s informed but informal brand of art criticism. It was a proto-blog, essentially—one that makes the history of L.A.’s art scene appear much more horizontal and diverse than it does in much written history.

As the newsletter became more established, so did its political position. Zlotnick championed L.A.’s fledgling feminist spaces—“WOMANSPACE is opening. WOMANSPACE is opening. WOMANSPACE is opening. WOMANSPACE is opening,” she wrote in 1973—and noticed when women took on curatorial positions around L.A. In March 1974, she noted that Barbara Haskell and Carol Marsden were at the helm of the Pasadena Museum of Art (“could only happen in California!” she quipped), the opening of Ruth Schaffner’s new gallery on Melrose, and that Marcia Weisman—“ANOTHER WOMAN”—had organized art for California senators’ offices.

Photograph of Diana Zlotnick by Adam Moskowitz, October 31, 2016.

In the mid-1970s, Zlotnick began leaning more heavily into criticism. After Norton Simon bought the Pasadena Museum of Art, she expressed skepticism over his renovation plans: “I think lavish buildings just make it more difficult to get into art, like mixing furniture with art: you can’t make clear visual distinctions.”

When the Los Angeles County Museum of Art hired Andrea Rich as director in 1999, Zlotnick wrote her an open letter that encapsulated her own ethos: “I see this as a move away from dogma and conservatism, opening up new avenues to define and redefine our systems of thinking and seeing, which we call ART.”

A Life in Art

In the decade before her death, Zlotnick talked often about the fate of her 600-work-strong collection, and the possibility of keeping it together. (At its height, it numbered nearly 900, but Zlotnick donated some and sold others to pay for health care.) “There would be no way my sister and I would be able to keep that collection,” Shirley said, “but I also sort of feel like she had it for so long, and it’s time for it all to have new homes.”

While her daughters donated some works to museums, many others hit the block at a seven-hour sale at Los Angeles Modern Auctions’s Van Nuys warehouse in May. It yielded $2.1 million, exceeding the low estimate of $897,450.

Obvious artworks did well: the Warhol Marilyn screenprint Zlotnick bought from OK Harris Gallery in 1971 netted $187,500; a Wallace Berman Verifax collage went for $143,750. The sale also established new records for some of the artists who remained starkly undervalued by the market during her lifetime (and whose works she mostly bought right out of the studio): a bold, bodily assemblage by Ron Miyashiro went for $21,250; Guy de Cointet’s Lost at Sea (…from a lagoon to another), a prop from a 1975 performance, went for $105,000; romantic yet comedic ceramics by Magdalena and Michael Frimkiss went for up to $43,750.

Zlotnick started collecting ceramics by the Frimkisses in depth in the 1980s. “She loved to have them out,” Shirley said, “and when she died, all the pots were out in what would’ve been the dining room. For many reasons, she didn’t want to leave the house and go to some sort of senior living facility, but some of it was just that she couldn’t part with the art. I’m not saying that her family wasn’t important, but she was just really obsessed with the art.”

Ceramics in Zlotnick’s collection. Photo: Marianne Shirley

As Zlotnick found it more difficult to go out, Green recalled she “really enjoyed playing with her artwork.” She would create ever-shifting installations, sometimes grouping all the work by one artist together, sometimes making smart juxtapositions.

“The amazing thing about visiting her there was that she moved things around all the time,” dealer Adam Moskowitz recalled. He first met Zlotnick in 2016 when she came to the gallery with a cut-out Times review of their current Valerie Green exhibition pasted into her planner. “She was looking at each of the works for five full minutes and then going back around and doing it again,” Moskowitz said. She stayed at the gallery for two hours that day, then kept coming back.

In her December 2013 newsletter, Zlotnick offered some end-of-year advice to her readers: “Collect art that cancels out the rest of the world / appreciate the new and that which you don’t immediately understand / stay active and in the discourse.”