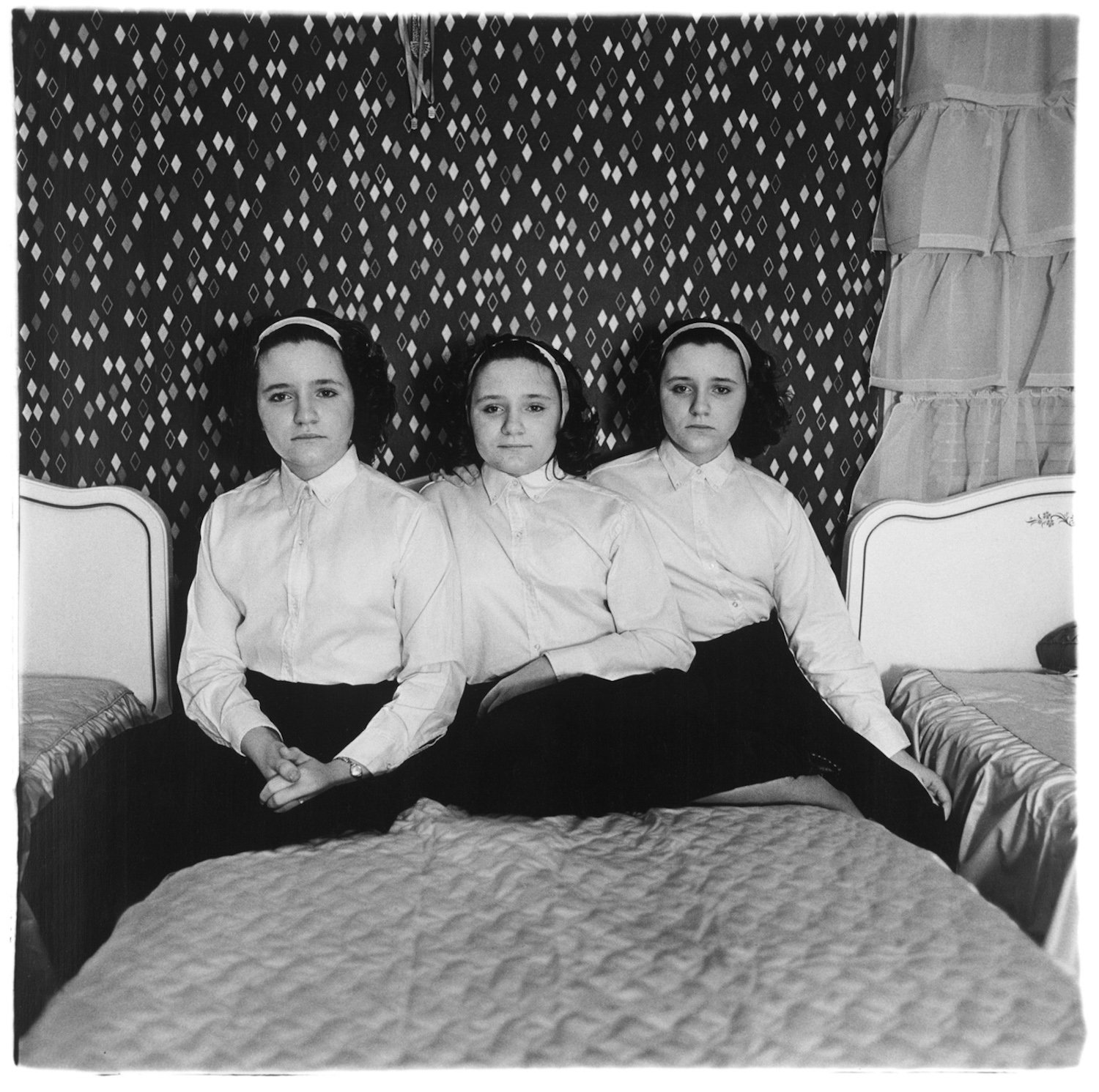

A 1972 retrospective of Diane Arbus’s work, mounted at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) just one year after she took her own life, divided viewers the way few exhibitions ever have.

New York Times critic Hilton Kramer called it “an artistic and a human triumph,” praising the late photographer’s ability to “inhabit the mind and body and the milieu of certain people society has judged to be abnormal or unusual.” On this same topic Susan Sontag took issue, writing—somewhat infamously—that the artist’s “work shows people who are pathetic, pitiable, as well as repulsive, but it does not arouse any compassionate feelings.”

“Arbus’s photographs,” Sontag went on, “suggest a naïveté which is both coy and sinister, for it is based on distance, on privilege, on a feeling that what the viewer is asked to look at is really other.”

A word-of-mouth sensation both revered and reviled, the show drew out-the-door, around-the-block lines, quickly becoming the museum’s most-attended solo exhibition to date. “People went through that exhibition as though they were in line for communion,” John Szarkowski, MoMA’s legendary director of photography who curated the retrospective, once recalled.

It’s no stretch to say that the show changed the way photography, a once-marginalized art form, was perceived by the institutional art world. And now, a full 50 years later, it’s going on view again.

Diane Arbus, Four people at a gallery opening, N.Y.C. (1968). © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

Opening today at David Zwirner in New York is “Cataclysm,” a recreation of the 1972 show, down to the last picture.

Organized by Zwirner and Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco, who jointly represent the Arbus estate, the show brings together 113 of the artist’s photographs across two floors and seven gallery spaces. It’s a museum-quality presentation, with all the prints secured via loan or consignment; some of them actually hung on MoMA’s walls in 1972. (No new estate-approved prints of Arbus’s pictures have been made since 2003.)

The name, “Cataclysm,” refers to the unexpected impact of the retrospective. “The pictures had a cataclysmic effect,” said dealer Jeffrey Fraenkel, who has worked with the Arbus estate since founding his eponymous gallery in 1979. “When people walked into MoMA and saw these photographs—BAM! No one had seen anything like them before,”

“[Arbus] went further than anyone had and took chances and was so courageous,” Fraenkel explained. “’Fearless’ is the word. That was part of the electricity people were touched by.”

Diane Arbus, Tattooed man at a carnival, MD. (1970). © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

Arbus’s photographs, now among the most recognizable in art history, won’t have the same effect this time around. And for cynics, restaging a historic exhibition will surely feel, at first blush, contrived—a gimmick akin to, say, bringing Star Wars back into theaters for the umpteenth time.

The business appeal is easy enough to see: for collectors, it’s the rare opportunity to collect Arbus’s greatest hits; for the galleries, the profit such an opportunity affords. Prices range from $10,000 to $175,000 for posthumous prints, and $40,000 to “close to a million” for prints made by Arbus herself, according to David Leiber, a partner at Zwirner.

But there’s non-monetary value in putting on this particular show again, too.

Today, photography is cemented in the firmament of the contemporary art world, just as Arbus is cemented in its canon. Far more precarious, though, are the questions raised by her work—the same questions that stoked a furor five decades ago: Society otherized Arbus’s subjects, but did she? Can photographs empower, or do they only objectify? What does it mean to look?

Diane Arbus, A very young baby, N.Y.C. [Anderson Hays Cooper] (1968). © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

Indeed, to engage with Arbus’s pictures is to engage with what it means to take a photograph of another human. And that, Fraenkel said, is an exercise just as vital in 2022 as it was in 1972.

“These are pictures I know very well. But when I walked into the gallery yesterday and turned left and saw a picture…I felt as if I was seeing it for the first time,” Fraenkel recalled upon visiting “Cataclysm.” “It sent lightning through my system.”

“There is nothing about the pictures that feels old. They feel thoroughly alive and speaking to us in this moment.”

Diane Arbus, Woman in a rose hat, N.Y.C. (1966). © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

”Cataclysm: The 1972 Diane Arbus Retrospective Revisited” is on view now through October 22 at David Zwirner in New York.