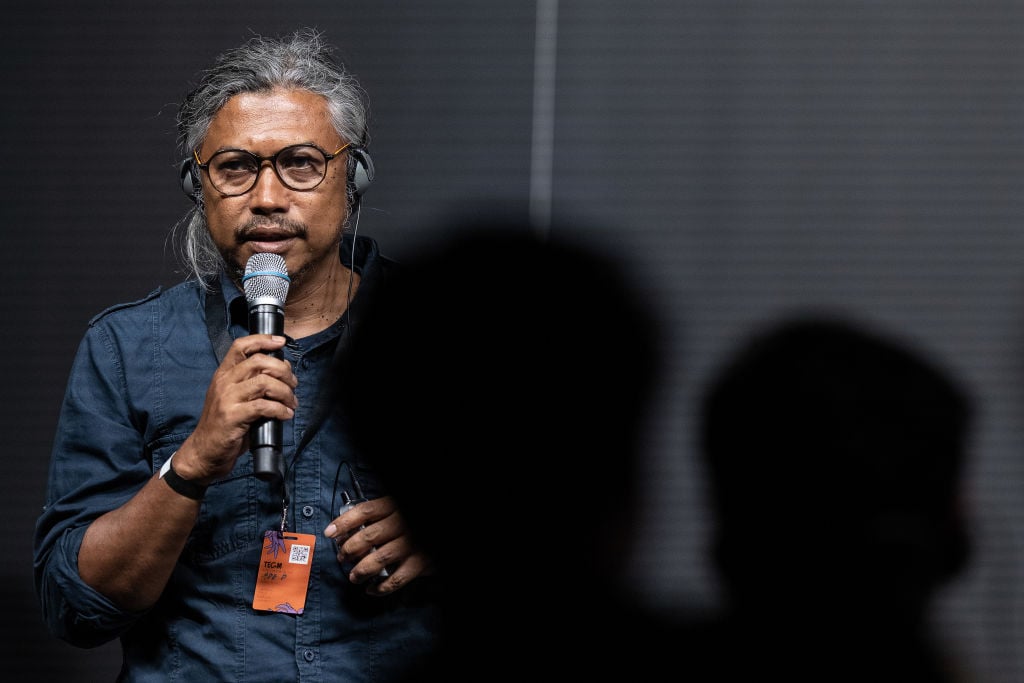

Before the panel began, Ade Darmawan, a member of the collective Ruangrupa and one of the curators of this year’s Documenta, stood up before the audience and took the microphone.

“We are here to learn and to listen,” Darmawan said of the talk, which was staged rather suddenly to address antisemitic imagery that had been identified in the collective’s exhibition. “We hope this event will be a trigger for other important events and discussions that will happen during Documenta.”

The panel, organized by Documenta’s parent company and the Anne Frank education center, did not include Ruangrupa members or any artists. It took place on Wednesday, June 29, after months of speculation swirled in the media over what some worried were antisemitic attitudes in the show. The suspicions spiraled when viewers discovered that one artwork contained antisemitic imagery. Indonesian collective Taring Padi’s People’s Justice (2002), which reflects on the end of their country’s brutal dictatorial regime, has numerous satirical characters in it—including a fanged and bloody-eyed Orthodox Jew with an SS insignia on his hat. One panel over, an Israeli soldier is depicted as a pig.

The artwork was removed from the prestigious show just days after its opening, on June 18, and Ruangrupa, Taring Padi, and Documenta’s administrative organizers sent out statements of apology. Still, it seemed the damage had been done to the event’s reputation.

The large painting People’s Justice (2002) by the Indonesian collective Taring Padi, covered with black cloth, on Friedrichsplatz. Several antisemitic motifs could be seen on the banner. Photo: Uwe Zucchi/dpa via Getty Images.

In the dramatic saga that has been unfolding since January, the notion of who should have a public voice on the subject has become a central point of contention; last night’s emergency discussion about antisemitism in art came only after Documenta canceled an earlier conversation series in April, when it was accused of bias.

In particular, the Central Council for the Jews expressed concern that it had been excluded from organizing or advising on the earlier event, and about the third panel, which was on anti-Muslim and anti-Palestinian racism in Germany.

“There was no invitation to Israeli Jewish artists and that showed us that something was getting out of control,” reiterated Doron Kiesel from the Central Council for the Jews, which represents Jewish people in Germany, when speaking on the panel this week. “Something then happened, which in our worst nightmares could not happen,” he added, with reference to the momentary presence Taring Padi’s work. “Our trust is in shreds.”

The panel, organized by the Bildungsstätte Anne Frank and Documenta gGmbH on the topic of “Anti-Semitism in Art.” Photo by Swen Pförtner/picture alliance via Getty Images.

The June 29 panel included a group of experts steeped in the German context: Nikita Dhawan, professor of political theory and the history of ideas in Dresden; Kiesel, scientific director of the education department of Central Council for the Jews; Meron Mendel, director of the Anne Frank education center of Frankfurt; Adam Szymczyk, artistic director of Documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel; and Hortensia Völckers, artistic director of the German Federal Cultural Foundation.

Germany’s culture minister, Claudia Roth, who has faced calls for dismissal, was in the audience. On Friday, Roth laid out a five-point plan proposing reforms to the exhibition, which receives more than €40 million (nearly $42 million) each edition, some of which comes from the federal government. She said that “fundamental structural reform,” including more federal oversight, would be a prerequisite for future government funding of the show.

In a letter to Roth shared with local media, Kassel’s mayor then retorted that the city is able to manage the funding of the event itself. (The federal government provides less than €5 million.) Documenta does not need “state censorship,” said the mayor, Christian Geselle. For years, Documenta has been largely managed by the city of Kassel and an autonomous organization there, Documenta gGmBh.

“The primarily local responsibility for Documenta is out of proportion to its importance as one of the world’s most important art exhibitions,” Roth said in the statement.

Adam Szymczyk, freelance curator and author and artistic director of documenta 14 (right), and Nikita Dhawan, professor of political theory and history of ideas at the TU Dresden. Photo by Swen Pförtner/picture alliance via Getty Images.

In recent weeks, there have been calls to close the exhibition entirely. And while this panel introduced some much-needed nuance to the discussion, fewer than 180 people watched the English version, while 600 watched the German. Documenta’s future has never seemed so endangered.

Specific members of the artistic team, artists, and the curatorial team have faced allegations of antisemitism since the beginning of the year, when an anonymous blog called into question some of the participants’ links to the pro-Palestinian Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement. A media storm followed, and many felt that the exhibition participants and organizers in question were not open enough to dialogue. Ruangrupa said the allegations were “bad-faith attempts” to delegitimize them.

In her opening address during the panel on June 29, Angela Dorn, the regional minister of higher education, research, and art, said that those early concerns “were not taken seriously enough.”

Much of the discussion revolved around whether increased government oversight is indeed the best solution. Dorn underscored Roth’s official statement that structural change is necessary.

Völckers—artistic director of the German federal cultural foundation, a top funding body in Europe—cautioned against it. “Things like [the current scandal] threaten to destroy trust, and we need to protect the autonomy of these institutions,” she said. “The damage caused… is major.”

Dhawan, a postcolonial scholar, also came down on the side of maintaining independence. “We have to think about whether we want bureaucrats telling us what to think,” she said. “If we were to take seriously and be consistent about the call for censoring hate speech, our museums would empty.”

Kiesel, from the Central Council for Jews in Germany, said that there need to be limits when it comes to freedom of expression, a position shared by all of the panelists. “If you do not deal responsibly with what the liberal democracy has made you responsible for, we will all be losers,” said Kiesel. “We cannot be the guardian of the situation,” he added, referring to his organization.

Meron Mendel, director of the Anne Frank Education Center, speaks on the topic of “Anti-Semitism in Art” at a panel organized by the Anne Frank Education Center and the supporting organization documenta gGmbH. Photo: Swen Pförtner/dpa via Getty Images.

Mendel, of the Anne Frank institution, also emphasized the lack of Israeli-Jewish artists in the show. “The Israeli art scene is very much related to the peace movement, and they are a minority in Israel,” said Mendel. “I cannot prove whether [the exclusion of Israeli-Jewish artists] was intentional or not. Was it antisemitism? Was it anti-Israeli attitude? These are open questions.”

In the fallout from the People’s Justice, Mendel was invited as an expert advisor to Documenta as it reviews the exhibition for further instances of antisemitic art. In his conversations over the past week, he said that he continues to hear about a “silent boycott” against Israeli-Jewish artists. “It is getting stronger. Yet there is no evidence that this happens.”

Mendel also called for moderation and deescalation in what has become an incredibly tense environment. The opening of the show saw both pro-Israel and pro-Palestine protests.

“If this was only this mural and someone saw and it was taken down, we wouldn’t have this scandal,” said Mendel. “But this now is the consequence of the fact that, since January, we have not been able to have a dialogue. I know that Ruangrupa has been working with their concept, but we still have not managed to have an exchange.”

Szymczyk, who curated the last edition of Documenta, stressed that the curatorial and artistic teams are under pressure when it comes to German discourse. “If the outcome is, in the public view—and I don’t mean academic circles—that the Global South becomes a toxin that brings antisemitism, that is a huge loss.”

Ruangrupa has vehemently denied accusations of antisemitism. Around the time that the group canceled talks on the subject, one of the venues hosting a Palestinian collective was vandalized with the tags “187,” which stands for a U.S. penal code and has been interpreted as a murder threat, and the name “Peralta,” a Spanish far-right political figure.

A tense moment in the panel emerged around the discussion of postcolonialism, a major subject in an exhibition of artists largely from countries in the Global South. Kiesel criticized what he saw as the conflation of the Israeli government with the Israeli state in postcolonial discourse. He also said that exchange on this theme seems impossible.

“You cannot talk about colonialism without talking antisemitism,” said Dhawan. “I am disheartened that you say dialogue is not possible.” She added: “Dismissing postcolonial discourse is an ideological maneuver, in some cases, to not address the legacies of European colonialism and the crimes against colonial people.” Her statement prompted applause from the audience.

There was both a sense of frustration at the end and a seed of optimism because, finally, the dialogue that the media and public has been asking for was beginning. “Documenta is once again proving its relevance as a place where discussion can begin, though I am sorry that it began in such violence,” said curator Szymczyk. “We cannot exclude one for another.”