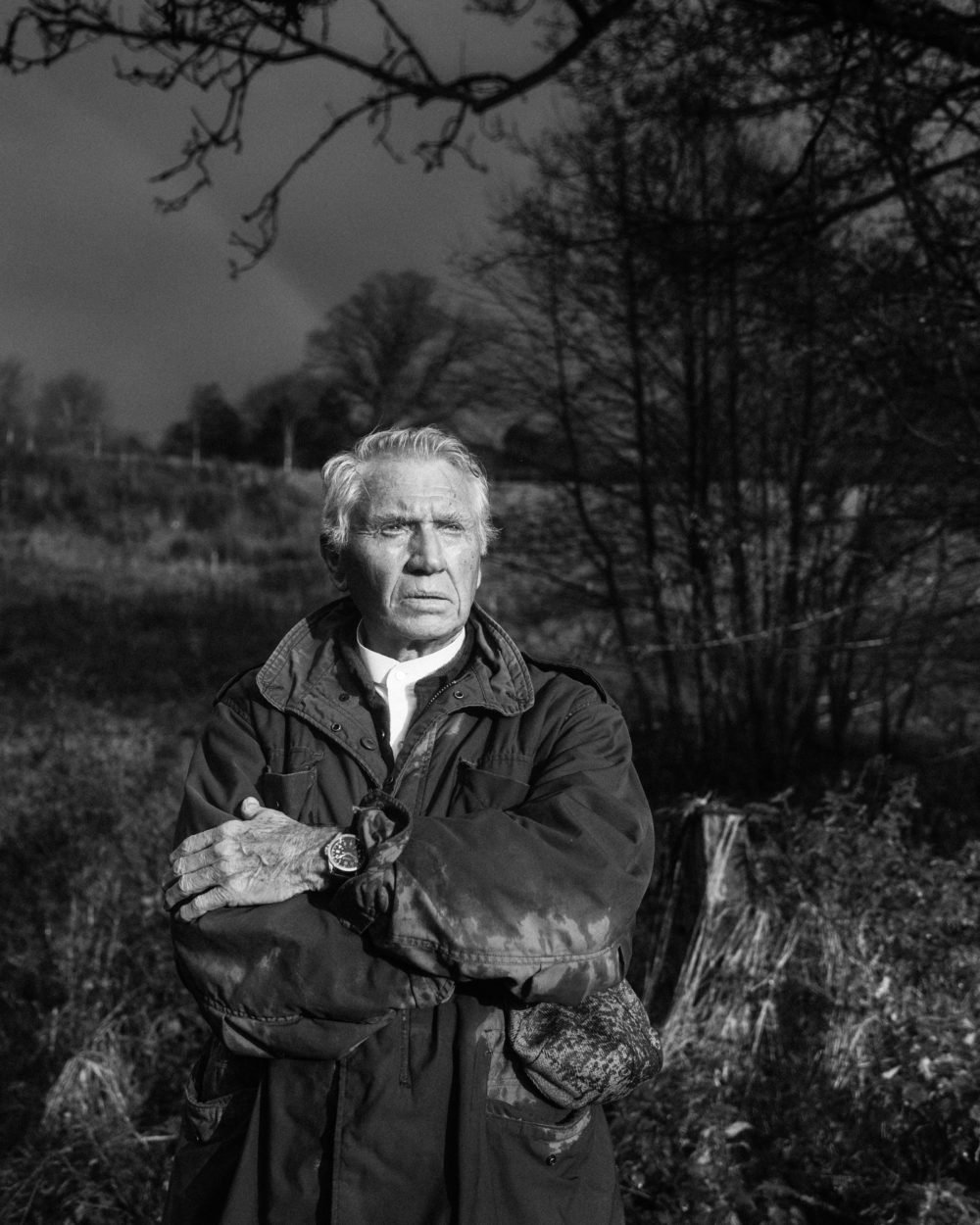

Don McCullin is not afraid of the dark.

The 84-year-old British photographer, who is famed for his haunting images, is best known for his salient photographs of war and conflict, taken around the world. For 60 years, he has reported on battles and destruction, chronicled starvation and inner-city poverty, and traveled the world working for newspapers including the Observer and the Sunday Times Magazine.

But I met him a long way from all that, in the peaceful countryside setting of Somerset, where he’s having an exhibition at an outpost of the mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth. We were surrounded by McCullin’s signature black-and-white images, none of which depict starving children or shell-shocked marines. Instead, these dark prints are of landscapes, many taken in the quiet fields surrounding his home.

Don McCullin, The Somerset levels at dusk (1998). © Don McCullin. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

“I owe something to Somerset,” McCullin says. This countryside gave him refuge during World War II, when he and other children were evacuated there from London during the Blitz. He only stayed for a few years, but the landscape stuck with him, and years of travel eventually brought him back.

When he first returned he was “very depressed,” traumatized from years of witnessing unimaginable horrors, and found it difficult to escape the guilt of covering wars that never seemed to stop coming. The landscape once again offered him asylum, and he has now been living there for the past three decades. He is still sharp in his 80s, and teases people with gallows humor, cracking jokes about his own death.

McCullin has been taking landscape photographs since the 1990s, capturing scenes from across the United Kingdom, Europe, and Asia when not on assignment.

The years of dodging bullets and photographing subjects on the move trained his eye to be quick, but this slower work hinges more on patience. Inspired by John Constable’s landscapes, he says it’s all about waiting for the right sky—and sometimes that can take months.

“I don’t work in the summer,” he says. He prefers the “much more expressive” wintertime sky.

Don McCullin, The Road to the Somme, France (1999). ©Don McCullin. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

But somehow, the stark black-and-white images still look like muddy battlefields. Pools of water form in a set of tire tracks across a field, summoning up a muddy trench, and reflect a moody sky. A dead sparrow resting on a snowbank is a poignant memento mori.

“A lot of people who look at my landscapes think they look like wars,” McCullin says. “I don’t do this intentionally. It’s a subconscious act.”

McCullin selected the 70-odd works on view from some 60,000 negatives, and he personally printed all of them in his dark room at home. In the beginning, the manual labor was a sort of therapy, distracting him from thoughts of the horrors he had witnessed.

“There’s a lot of me in these pictures,” he says. “A lot of my integrity and a lot of my emotional thoughts.”

Don McCullin, Batcombe Vale (1992/93). ©Don McCullin. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Unsurprisingly, a darkness pervades the images, and he says some people are confused about whether he is trying to frighten them or bring them pleasure. In the end, it is a little bit of both.

“I want my pictures to have an impact. I don’t want people to walk away without remembering them.”

This summer, McCullin’s hugely successful retrospective, which opened at Tate Britain last year, travels to Tate Liverpool. But he is adamant that his photographs are not art.

Not even—he insists on this point—the still-life compositions that he shot in his garden, which were inspired by the Dutch Old Masters.

“I am a photographer, not an artist,” he says. He deems the conflation a “very American” way of thinking. “A lot of American photographers call themselves artists. I don’t make art. I use composition, but it is not art.”

Don McCullin, Looking forward to the valley of the tombs which Isis have destroyed (2016). ©Don McCullin. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Some of McCullin’s recent landscapes include photographs from his ongoing “Southern Frontiers” series. He has documented Roman ruins in North Africa and the Levant, including the recent deliberate destruction of the ancient site of Palmyra in Syria by ISIS.

The images seem to tie together the two strands of his practice: war and landscapes.

Back home in Somerset, he sees a new battlefront forming. There is a plague of development projects impinging on the beautiful landscape where he has found a home.

“It is such a euphemism; they’re not developers at all,” McCullin says. “They want to dig the land up and build on it. They want to frack it.”

“Don McCullin. The Stillness of Life” is on view through May 4 at Hauser & Wirth Somerset. Watch McCullin speaking about his landscape pictures below.