The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMoCA) has for decades been a beacon for the Iranian people. During the 1979 Islamic Revolution, a human shield formed around the building to protect the art inside. In 2016, when plans to privatize the museum were made public, protests filled the street.

After two years of renovations, TMoCA—which houses the most valuable collection of Modern Western art outside Europe and North America—swung open its doors again on January 28. But that’s not the only reason the museum is back in the limelight.

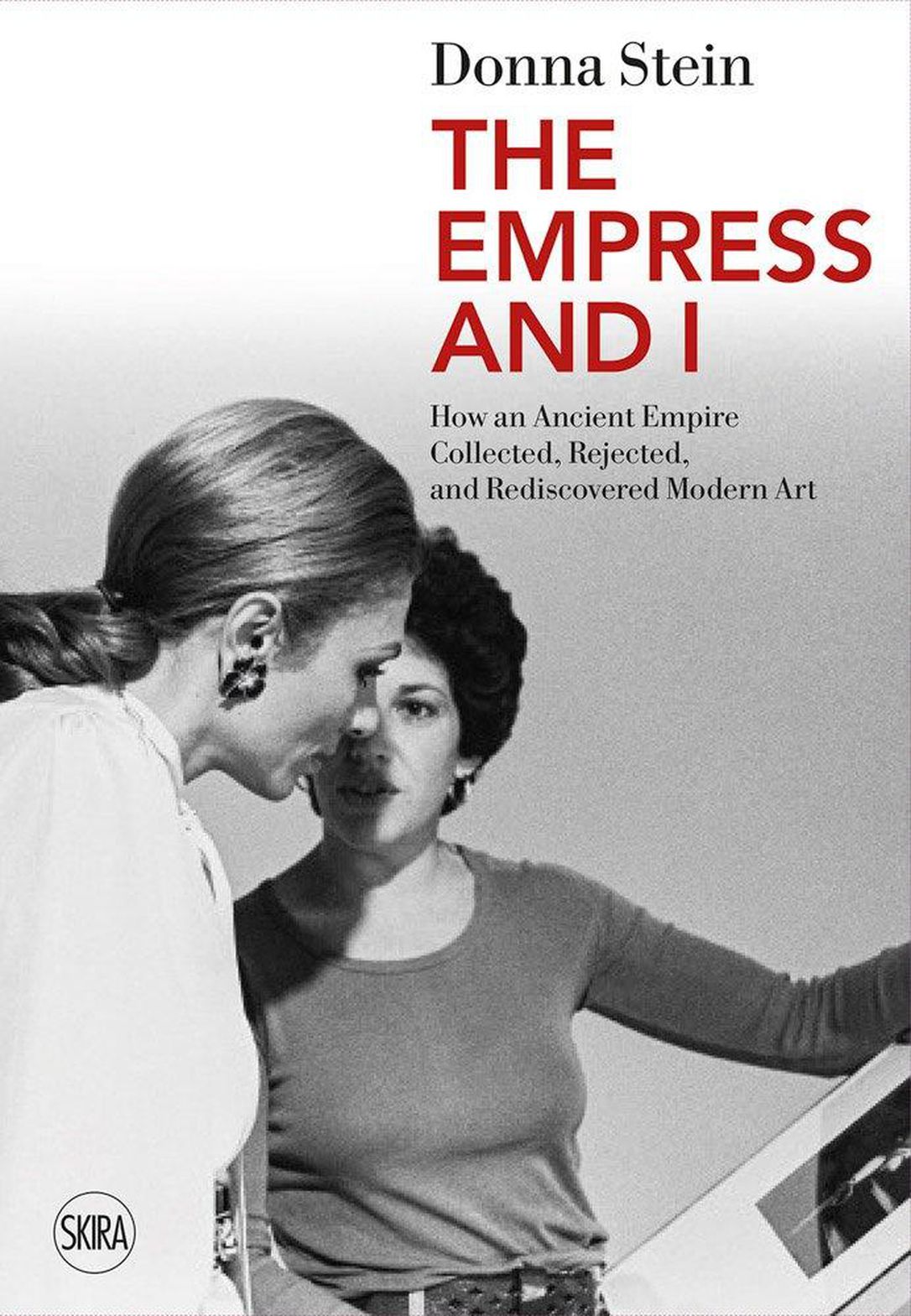

Its reopening coincided with the publication of a new book by Donna Stein, an American curator who lived in Tehran between 1975 and 1977 and assisted with the assembly of the famed collection. The 208-page book, The Empress and I: How an Ancient Empire Rejected and Rediscovered Modern Art, has garnered international headlines—and sparked controversy in the Iranian art world.

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. Courtesy of Kamran Diba.

Iranian art critics, patrons, and founding members of the museum say that Stein’s book—and the international coverage of it—perpetuates harmful stereotypes about Iranian society. They also claim that her role in building the collection is not as central as she suggests.

Stein disputes these characterizations. “My book is an effort to tell my story, what I know and remember, and I have documents and letters to support my conclusions,” she told Artnet News. “After 50 years, I think a picture of that time from a participant’s point of view is valuable and I want people to know the truth about the art and my role as an American woman living in Tehran during the mid-’70s.”

What is “true” in regards to the establishment of TMoCA’s famed collection, however, changes based on who tells its story.

The Role of the Museum

When TMoCA was inaugurated by Empress Farah Pahlavi, wife of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, at the height of Iran’s oil boom in 1977, it was lauded around the world for its impressive collection of Western art. Iran, a nation the world has come to know as repressive, was then open to the world and free.

To put things in perspective: The museum was inaugurated the same year as the Centre Pompidou in Paris and 25 years before the Tate Modern in London. Works by art history’s most esteemed names—Francis Bacon, Salvador Dalí, Andy Warhol, Robert Motherwell, and many more—were there. The collection is now valued at $3 billion to $4 billion, according to Kamran Diba, the museum’s architect and former director. Its vision was to display Western art alongside the work of Modern and contemporary Iranian artists.

From left: Empress Farah Pahlavi, founding patron of TMoCA; Kamran Diba, founding architect and director of TMoCA; and David Galloway, founding curator of TMoCA. Courtesy of Kamran Diba.

“TMoCA is a unique institution because it is the first museum of Modern art of international standards established in the Middle East and still not surpassed,” the Empress Farah Diba Pahlavi told Artnet News. “The museum and its world-class collection represent a symbol of modernity, which is a source of national pride for Iranians, offering collaboration with artists throughout the world.”

Then came the Islamic Revolution of 1979. In January of that year, the Empress and the Shah fled, never to return to their country again. The Shah died in exile in 1980 while the Empress divides her time between Paris and Washington, D.C. She continues to be a fervent supporter of the Iranian art scene from afar.

Controversial Claims

This backstory helps explain why the museum—and the narrative that surrounds it—is so precious to many Iranians. It is also why they feel aggrieved when that narrative is, in their minds, misinterpreted.

Critics of Stein’s book, three of whom spoke to Artnet News, feel her story perpetuates harmful misrepresentations of the museum. When asked about these claims, the Empress, who is pictured with Stein on the cover of the book, declined to provide further comment.

Critics claim Stein takes credit for playing a larger role in the museum’s formation than she actually did. “In my opinion, Donna Stein was a young employee without much experience,” Diba, who is also the Empress’s first cousin, told Artnet News. As director, he was personally responsible for purchasing key works, including Andy Warhol’s Suicide (Purple Jumping Man) (1965), for $81,400, and Jasper Johns’s Passage Two (1966) for $255,000.

Andy Warhol’s Suicide (Purple Jumping Man) (1965). Courtesy of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

TMoCA’s acquisition process was a collaborative effort. In two interviews given to Dubai-based journalist Myrna Ayad for Canvas and The Art Newspaper, Farah Diba Pahlavi credited founding director Diba, chief of staff Karim Pasha Bahadori, founding curator David Galloway, and lastly, Stein for “shaping the collection.”

While Stein claimed to have played a central role in selecting works on paper (including prints, drawings, and photographs) as well as paintings and sculptures, Diba said she was involved largely in building the photography collection, which he does not consider to be the strongest part of the museum’s holdings.

“Going through the pages of the photography collection catalogue alongside prints which she helped assemble, it quickly became obvious to anyone in the know that none of the key pieces that should have been acquired as part of a worthwhile collection of contemporary art of the time were in fact acquired,” he told Artnet News.

Author and curator Donna Stein. Courtesy of Skira.

Stein—who had previously worked as an assistant curator in the prints and illustrated books department of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and was hired after traveling to Iran on a National Endowment for the Arts grant—says her contribution was underplayed because of her nationality and gender.

“Many people took credit for the work that I had done,” Stein said, noting that the empress did not acknowledge her involvement officially until 2013, when she contributed a chapter about her experience to a book on Iranian visual culture.

In an interview with Artnet News, Stein went even further than she did in the book, contending that she also advised on Iranian artists for the collection in consultation with other curators. “What I didn’t say in the book was that not only was I choosing the Western works in the collection, but I also was choosing Iranian works,” she said. (She added that she kept “careful files of both the Western and contemporary Iranian acquisitions, which I recently learned are archived at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.”)

Culture Clash

In addition to the story of TMoCA and its collection, Stein also recounts her experiences as a single American woman living in Tehran during the mid-’70s and how she was often mocked for what Iranians then saw as her unusual lifestyle.

“Iranians at the time had no conception of women who lived alone; a woman either lived with her family or was married,” she said. “I was neither. It was a strange society for someone like myself who was young and adventurous and a hard worker.”

Kamran Diba in the center, with his curatorial and museum staff. Courtesy of Kamran Diba.

But some in the Iranian art world interpreted her account, accompanied by her comments in international press, as what Maryam Eisler, former chair of the Middle East acquisitions committee at the Tate, called an “accusatory chronicle of an Iranian society.” Eisler points to a New York Times interview in which Stein described Iran as “the Third World” and the museum’s audience as “uneducated.”

“Perhaps a reminder is in order to counter such stale ‘orientalist’ narratives; in fact, the ‘educated’ amongst us universally recognize Iran to be one of the greatest cradles of civilization,” Eisler said.

Testament to Iran’s Living Memory

Against a backdrop of political repression, rising inflation, and continued sanctions in Iran, some might question why the story of the TMoCA matters at all, or why those involved in the museum are going to such lengths to, in their minds, correct the record—both in regard to Stein’s book and international news coverage.

“Each time TMoCA’s Western art is exhibited, someone writes an article about how this is the first time this art has been seen since the revolution, usually accompanied by a photograph of a veiled woman looking at Warhol or Giacometti,” said Shiva Balaghi, a cultural historian specializing in Middle Eastern art. “Maintaining the myth of novelty—for whatever reason—becomes an act of cultural erasure. It erases the traces, often ephemeral, with which we write histories of art and develop better understandings of the role of art in society.”

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. Courtesy of Kamran Diba.

For a country that has been secluded to the world for decades, it has always been through its art that Iran has communicated with the outside world. TMoCA is the epitome of Iran’s powerful belief in art and culture; in many ways, it is its last symbol of freedom.

“What people tend to forget is that this museum was just as much about creating an important cultural dialogue and interplay between the great Western artists of the period and their Iranian counterparts, me being one,” prominent Iranian artist Parviz Tanavoli told Artnet News. “That, to me, is the greatest legacy of the collection—not only internationally, but also, and most importantly, for the people of Iran.”