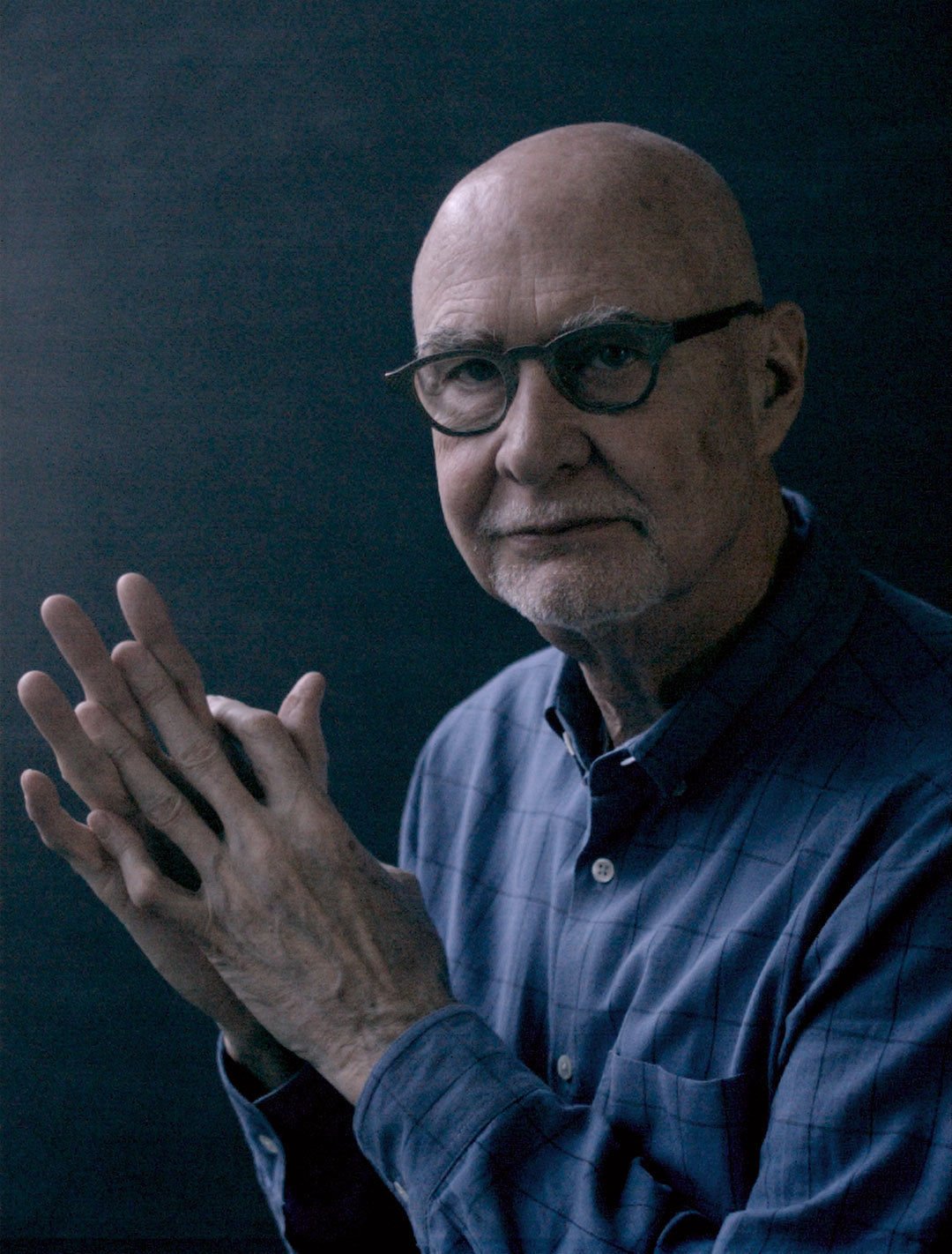

Douglas Crimp, the art critic and curator who made his name with the landmark “Pictures” exhibition that defined a generation of artists, and who later went on to write fiercely polemical essays on the AIDS crisis and the history of museums, died on Friday at the age of 74.

His death was confirmed by the University of Rochester, where he had long been a professor of art history.

Crimp’s big break came in 1977, when he organized “Pictures” for the non-profit gallery Artists Space in New York. But few would have guessed at the time that the show would eventually be considered seminal. “None of the initial reviews of ‘Pictures’ suggest[ed] that the show was especially momentous,” Crimp once said.

The show was small and included only five artists: Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo, and Philip Smith. But it grew to have an enormous influence on the development and reception of subsequent art. Crimp had shown striking intuition in observing that recognizable images, after a long period of seeming dormancy, were making a forceful return to contemporary art.

In years to come, the “Pictures Generation” came to encompass the work of the most famous artists of the day, including Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, and Dara Birnbaum, among others.

Crimp later said that at the time he was writing the catalogue essay, he was “convinced that with sufficient insight a critic could—even should—determine what was historically significant at a given moment and explain why.”

In the years since, Crimp’s position and interests slowly began to shift, and his certainties were shaken by the swift rise of the AIDS epidemic in New York, where he had lived since 1967. As he watched young men and women of his generation die painful, gruesome deaths, he joined a wave of activists and writers who demanded that more resources be put into the crisis.

Crimp’s best essays and sharpest observations, published as a collection in 2002 with the title Melancholia and Moralism, were made in these darkest hours. “Anything said or done about AIDS that does not give precedence to the knowledge, needs, and the demands of people living with AIDS must be condemned,” he wrote in 1987.

Crimp’s research into the medical, governmental, and political power structures that governed the epidemic soon spun off into a new focus on the histories of art institutions, which led to one of his most influential books, On the Museum’s Ruins (1993). His essays, published alongside commissioned photos by Louise Lawler, forcefully denied the fiction that museums are neutral repositories for the world’s greatest treasures.

Crimp was born in 1944 in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, where the Calvinist essayist Marilynne Robinson was among his childhood friends. He found the small town provincial and stifling, and escaped in 1962 to New Orleans, where he enrolled at Tulane University and took up studies in art history. From 1977 until 1990, he was an editor at October magazine, the publication founded in 1976 by Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson.

Despite his many achievements, Crimp admitted in his 2016 memoir, Before Pictures, that the Artists Space show would indeed be his longest-lasting legacy—a fact about which he felt uncertain.

“Coming to the understanding that my knowledge of art can never be anything but partial has been liberating,” he wrote. “It has allowed me to write about what attracts me, challenges me, or simply gives me pleasure without having to make a grand historical claim for it. No doubt that is why I respond to the reception of ‘Pictures’ with ambivalence. It historicizes me.”