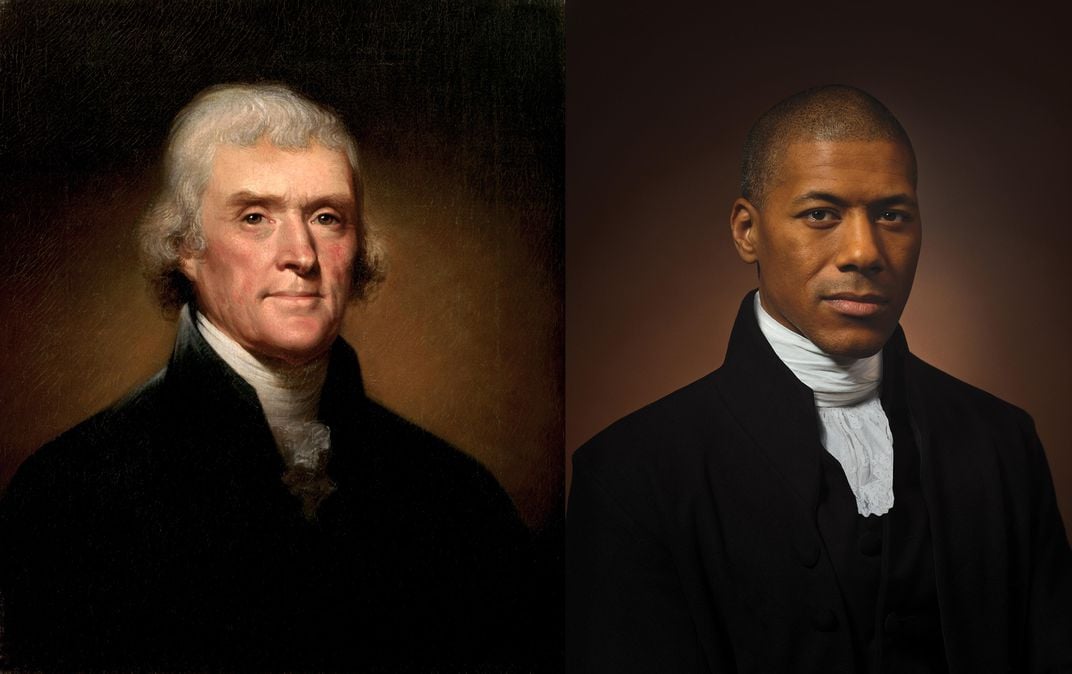

For the past 15 years, the British photographer Drew Gardner has been tracking down the blood relatives of famous historical figures and posing them in their relatives’ likenesses.

For Shannon LaNier, a Houston-based television anchor, this was a particularly uncomfortable task. LaNier is a descendant of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, who is thought to have given birth to at least six children while enslaved at Jefferson’s plantation.

The artist described the project, titled “The Descendants,” as a “kickback at, or acknowledgement of, celebrity culture,” but his real mission is to expose the links between historical figures and their descendants who walk the streets every day.

Gardner says the project was in the works long before the death of George Floyd and the recent global rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, the images, particularly that of Jefferson juxtaposed with LaNier, are striking a chord with viewers today.

For the first decade, the series focused on icons of European history: Napoleon Bonaparte, Charles Dickens, William Wordsworth, and even a distant relative of Lisa del Giocondo, better known as the model for Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. The most recent iteration turns to three giants of American history: Thomas Jefferson, Frederick Douglass, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

“One of my burning desires in the whole project is to show that history is not straightforward; it’s really quite diverse,” Gardner told Artnet News. Adding that he was “painfully aware of a lack of diversity in my set,” he decided to embark on this latest trio of photographs, which were commissioned by Smithsonian magazine and published in its July issue.

Left, Frederick Douglass, courtesy of Edwin Burke Ives and Reuben L. Andrews / Courtesy of Hillsdale College; right: Kenneth Morris, Photo © Drew Gardner, @drewgardnerphotographer. Courtesy Smithsonian Magazine.

Once Gardner decides on a historical subject, he researches the person’s direct descendants, embarking on often circuitous paths that commonly lead to dead ends. The trick, he says, is to find a relative who is around the same age as the subject when the original source portrait was made; then he must make contact and convince the relative to dress in the same style and sit for a photograph.

“Not many people say no, but when they do it’s quite disappointing,” he says.

LaNier was one of those people at first. And even when he did agree to participate, he declined to wear a wig that would make him appear more white. “I didn’t want to become Jefferson,” he told Smithsonian. “He was a brilliant man who preached equality, but he didn’t practice it. He owned people. And now I’m here because of it.”

Monticello, in Charlottesville, Virginia. Designated as a world heritage site in 1987. Image courtesy of Wikimedia.

LaNier’s complicated feelings about his sixth-great-grandfather are echoed in an opinion column penned by yet another of Jefferson’s descendants, Lucian K. Truscott IV, who calls for the removal of the Jefferson Memorial on Washington’s National Mall.

“Described by the National Park Service as a ‘shrine to freedom,'” he writes, “it is anything but. The memorial is a shrine to a man who during his lifetime owned more than 600 slaves and had a least six children with one of them… upon his death he did not free the people he enslaved, other than those in the Hemings family, some of whom were his own children. He sold everyone else to pay off his debts.”

Instead of a bronze statue of his relative, Truscott says he’d like to see one of Harriet Tubman, “who was a slave and also a patriot.”

Monticello, which now has an exhibition dedicated to Sally Hemings and the slaves who built the property, is enough to remember Jefferson by, Truscott says. “The ground, which should have moved long ago, has at last shifted beneath us.”