How did the acclaimed American artist Edward Hopper learn to paint? By copying other artists’ work out of instructional art magazines, it appears.

A graduate student at the Courtauld Institute in London has discovered that at least four early oil paintings by Hopper were actually copies of work created by other artists. The paintings were previously thought to be scenes Hopper made in his hometown of Nyack, New York.

Louis Shadwick published his findings in Burlington Magazine, concluding that it is possible “Hopper did not produce a single original oil painting until he enrolled at the New York School of Art in the autumn of 1900 and that no boyhood oils of Nyack by him exist.”

Shadwick made his discovery by referring to old copies of the Art Interchange, a popular periodical for art amateurs and students in the late 19th century. An annual subscription came with 26 collectible color prints reproducing original artworks, as well as instructions aimed at teaching amateur artists how to reproduce them—and it seems the Hopper family may have been subscribers.

Edward Hopper as a child, with his sister, Marion. Photo courtesy of the Sanborn-Hopper Family Archive.

The earliest known Hopper oil painting, Rowboat in rocky cove first oil (1895), is a dead ringer for a watercolor by an unknown artist published in the Art Interchange in 1891. Titled Lake view, the original work was not a view of Nyack, as has been long assumed, but of a lake in Athelstane, Wisconsin. The instructions on how to reproduce it promised readers that the painting was “a very simple subject and well adapted to beginners.”

“There is little mystery, then, as to why Hopper copied it for his first attempt at oil painting; indeed, his beginnings as a painter seem to have been more tentative than has previously been imagined,” wrote Shadwick.

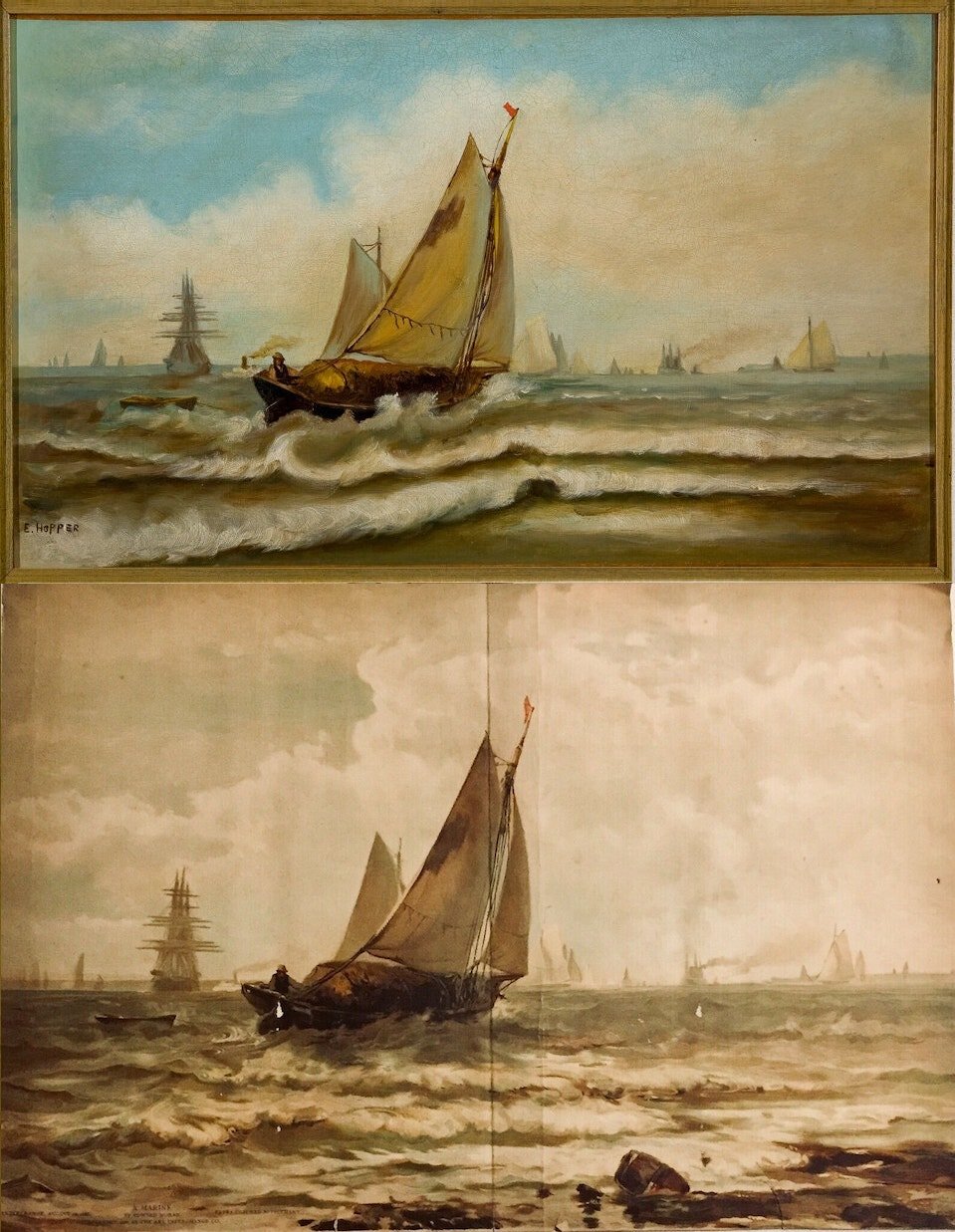

Two other Hopper paintings can be traced to Art Interchange. His early work Ships (c. 1898) is a copy after A marine (1880) by the American painter Edward Moran, reproduced in the magazine with instructions in August 1886.

Edward Hopper, Rowboat in rocky cove (1895).

Photo courtesy of the Frick Art Reference Library, New York. Unknown artist, Lake view (‘Athelstane’) (c. 1880s). Reproduced in the Art Interchange, February 1891. Photo by Louis Shadwick.

And then there’s Hopper’s Old Ice Pond at Nyack (c. 1897). Likely painted when the artist was just 15, the canvas was previously “thought to be one of his very few undoubted depictions in oil of the Nyack of his youth and one of his first signed paintings,” wrote Shadwick.

In actuality, the work is a replica of Winter Sunset by Bruce Crane, a Tonalist American painter. “Crane was nearing the height of his popularity when the reproduction was published,” in 1890, Shadwick noted.

Hopper also appears to have copied another early work, Church and landscape, as Shadwick discovered a Victorian porcelain plaque featuring the same scene during his research.

“Although its precise source remains unknown,” he wrote, “it certainly does not portray ‘a snowy Nyack Baptist church,’ as has been claimed.”

Edward Hopper, Church and Landscape (c. 1897) and a Victoria-era porcelain tray featuring the same composition, by an unknown artist. Photo courtesy of the heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

The origins of the early Hopper canvases Country road and Clipper ship being towed by tug are still unknown, but they “must be regarded with similar suspicion,” Shadwick wrote.

His discovery “cuts straight through the widely held perception of Hopper as an American original,” Kim Conaty, curator of drawings and prints at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, told the New York Times.

The artist’s early paintings remained in the attic of Hopper’s childhood home in Nyack—today the the Edward Hopper House Museum and Study Center—until after his death and the death of his older sister Marion.

Bruce Crane, A Winter Sunset reproduced in the Art Interchange magazine. Photo by Louis Shadwick.

The contents of the home were eventually acquired by Arthayer R. Sanborn, the preacher at the local Nyack Baptist Church, who appears to be responsible for introducing the misconception that the paintings were depictions of the Nyack landscape.

“This is a fascinating revelation, but one that does not reduce the importance of these paintings in the conversation of Hopper’s artistic journey,” wrote Hopper House chief storyteller Juliana Roth on the museum website.

“The myth of artistic genius is just that, a myth. No artist develops in a bubble, without influence, resource, or access,” she added. “Young Hopper copied freely and regularly, which is to say, he learned to see.”

Edward Hopper, Old Ice Pond at Nyack (c. 1897). Painted by Hopper as a teenager, the canvas is a copy of an earlier painting by Bruce Crane. Courtesy of the heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

One of the early Hoppers in question, Old Ice Pond at Nyack, is currently being sold by Heather James Fine Art, which has priced the work at $300,000 to $400,000. James did not respond to inquiries from Artnet News as to whether the value of the painting could be affected by the new revelations.

Hopper’s work has sold for as much as $91.9 million, with the 2018 sale of Chop Suey (1929) at Christie’s New York, according to the Artnet Price Database. Crane’s record at auction, by comparison, is just $51,400, set in 2008, while Moran’s work has sold for as much as $300,000, with the 2012 sale of Summer Morning, New York Bay.