Many artists can attest to stockpiling their earliest attempts at art-making, which typically end up decorating their parents’ homes. Under few circumstances would they seriously consider selling or exhibiting them. Edward Hopper (1882–1967) was in many ways one such artist, according to the art historian and curator Gail Levin who also authored Hopper’s catalogue raisonné and his biography.

So why would a slew of early Hopper artworks, which he had never wanted or intended to exhibit during his lifetime, suddenly appear on the market soon after his death, Levin has asked? The question has plagued the expert for years, particularly since Hopper’s widow, the artist Josephine Hopper, bequeathed all of her husband’s artwork, per his wish, to the Whitney Museum of American Art, an institution where Levin herself was the Hopper curator.

What’s more, how did Hopper’s local minister and friend in Nyack, New York, the Reverend Arthayer R. Sanborn, come to possess hundreds of the artist’s oeuvres, including many such early pieces, when Hopper and his wife were known to rarely part with them?

These questions continue to swirl around a self-portrait by Hopper in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Completed around 1903, when Hopper was just entering adulthood, the painting has recently made headlines, due to persistent questions about its previous owner: Sanborn, who died in 2007.

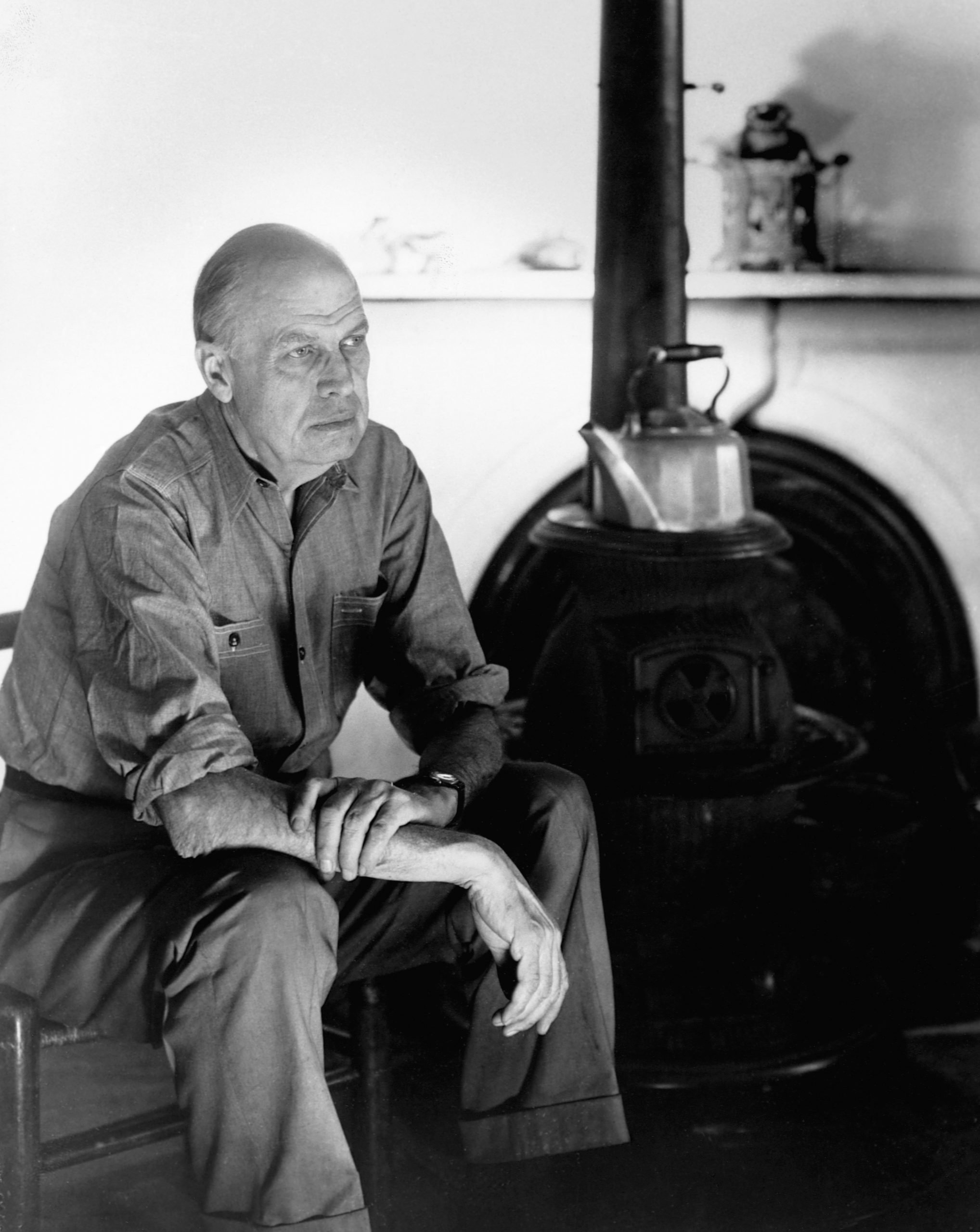

Edward Hopper, Self Portrait (about 1903). Photo: MFA Boston, The Hayden Collection—Charles Henry Hayden Fund.

While Sanborn said he received it as a gift from the artist’s sister, Marion Hopper, in an oral exchange around the time of her death in 1965, Levin maintains he simply helped himself to the painting and other documentation belonging to the Hopper family, because he had a key to their home. She also told the New York Times that in the 1970s, a frustrated Sanborn told her in person the Hoppers had not gifted him anything, behavior consistent with how other friends described the family’s habit of rarely gifting works, and carefully cataloging transactions.

“The suppressed story of how so many of Hopper’s works that he never intended to be on the market escaped from his estate needs to see the light of day,” writes Levin on her website. “I’m not making these accusations out of thin air,” she said, according to the Boston Globe. “I have evidence.”

Sanborn eventually sold more than 100 Hopper artworks, listed as gifts. He also said he purchased artworks from the Hopper estate soon after the couple’s deaths, but that would have conflicted with Mrs. Hopper’s will, which promised the artist’s works to the Whitney, which ultimately receive about 2,500 pieces. The museum also acquired a trove of about 4,000 objects and documents from the Sanborn family in 2017.

Despite Levin’s dogged insistence, the MFA and the Whitney have said there is no convincing proof to back her claims. Victoria Reed, MFA senior curator for provenance, told Artnet in a written statement that when the self-portrait was purchased by the museum, provenance was recorded in written and verbal form. “Those statements represent the best information we have about its history, and we can find no indication that they are incorrect or otherwise inaccurate. In fact, the provenance of many works of art in the collection has been supplied through verbal or written statements; these are by no means an unusual way to document ownership history.”

Following a thorough review, the curator said the museum was “satisfied” the provenance information it has, “accurately reflects what we know. We generally do not include speculative or hypothetical information in our provenance records without supporting evidence.”

More Trending Stories:

How an Exclusive NYC Cult Influenced the 1970’s Art Scene

A Rare Soulages Lithograph Possibly Worth $30,000 Sells For $130 in Facebook Marketplace Mishap

Masterpiece or Hot Mess? Here Are 7 Bad Paintings by Famous Artists

Is There a Hat Better Than Napoleon’s? We Rank Art History’s 5 Most Iconic Chapeaux