Though he died at just 28 from the Spanish Flu in 1918, Egon Schiele remains an enduring figure in art history, having achieved lasting fame with his erotic, overtly sexual drawings and paintings.

But for British author Sophie Haydock, the artist’s story as it was told in textbooks was incomplete. Who were the women depicted in these boundary-pushing drawings and paintings, which were at times condemned as pornographic?

In The Flames, Haydock’s debut novel, Schiele shares the narrative with four women whom he immortalized on paper and canvas in varied states of undress: his sister, Gertrude Schiele; his wife, Edith Harms; his sister-in-law, Adele Harms; and his mistress, Walburga “Wally” Neuzil (Vally in the book).

In Haydock’s telling, these were not just artist’s muses, passive beauties waiting to be captured by an artistic genius. They were deeply feeling, passionate women with rich interior lives, not only supportive of Schiele’s art, but instrumental in and essential to its creation.

Sophie Haydock, The Flames (2022). Courtesy of Doubleday.

The history books sketch the details of Schiele’s biography matter-of-factly, without considering the inevitable fallout there must have been when he broke things off with Neuzil to marry the more socially acceptable Edith in 1915.

Schiele never saw Neuzil again. She died of scarlet fever in October 1917, just 23 years of age, while serving as a military nurse in Dalmatia. Less than a year later, the artist too would be dead, three days after Edith, who had been carrying their first child.

And then there was Adele, who lived for decades after her sister and brother-in-laws’ untimely deaths, practically homeless at the time of her passing in 1968. She was buried, curiously, in Schiele’s grave, unmarked, next to Edith. (Gertrude alone seems to have escaped tragedy, though the later part of her life is shrouded in mystery.)

Sophie Haydock. Photo courtesy of the author.

Drawing on the limited historical records, Haydock, in comparison, has crafted an emotionally fraught narrative that explores the complex interpersonal relationships between these young people. The Flames is a churning sea of desire and yearning, jealousy and obsession, destruction and despair, and, of course, death.

We spoke to Haydock, who also runs the Instagram account @egonschieleswomen, about what inspired her to write about the life and career of the Austrian artist, the process of unearthing the lives of the women around him, and what she thinks Schiele’s sex life was really like.

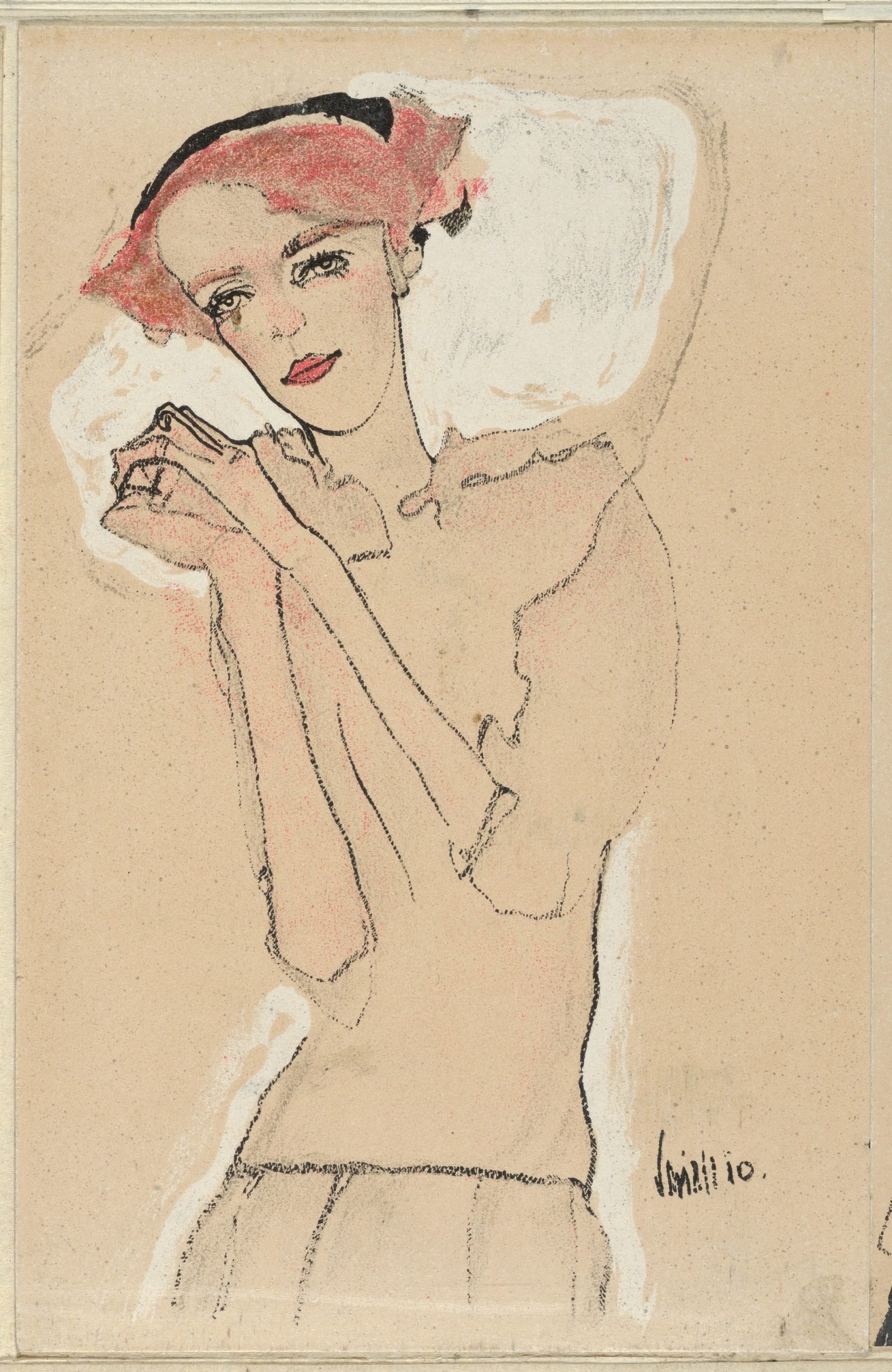

Egon Schiele, Self Portrait (1910). Collection of the Leopold Museum, Vienna.

The initial kernel of inspiration for this book came when your friend, Ali Schofield, took you to see a Schiele exhibition at London’s Courtauld Gallery in 2014. Before you saw that show, did you have any art history background?

I think the reason that Ali invited me is because we had both worked together in Leeds, at a Time Out-style listings magazine. I was arts editor there and Allie was lifestyle editor. I hadn’t studied history of art, but I’ve always had lots of friends who’ve been artists. I would always be going to like, the Venice Biennnale and exhibitions in the U.K. It felt like a world I was immersed in.

Did you want to write about Schiele’s women in part to make them more than these very erotic images, to counterbalance the artist’s male gaze?

A hundred percent. I actually had a postcard of Adele Harms on my wall at university, of one of Schiele’s most famous artworks, Seated Woman With Bent Knee. She’s got this green chemise on, and her legs have fallen open and she’s kind of revealing herself. She’s wearing bloomers, so she’s not naked, but she’s undressed. She’s sitting in this erotic, sensual pose, and she’s got this really beautiful, quite haunting look in her eyes.

Egon Schiele, Seated Woman with Legs Drawn Up (1917). The model for the work was the artist’s sister-in-law, Adele Harms. Collection of the

National Gallery in Prague.

I must have looked at this postcard pretty much every day during my final year at university. It wasn’t until I got to the gallery that day that I realized that this was a real living, breathing woman who had her own hopes and fears. I still didn’t know her name at that point. I didn’t know her relationship to the artist. When I found out that she was, in fact, the artist’s sister-in-law, that raised a huge number of questions for me.

It made me wonder what situation I’d have to be in to pose for my sister’s husband in my knickers. What I might have been feeling? What my motivations might have been? So yes, it was reclaiming these women from the male gaze, but it really was also reclaiming these women’s emotional lives for themselves.

In your research, you learned that in her old age, Adele told an art historian she had an affair with Schiele. What can you tell us about that?

That was Alessandra Comini, a famous scholar from Texas who’s in her 80s now. In the 1960s, she was the first person to go to Austria and record the locations that were associated with Egon Schiele. She went to Tulln, where he grew up next to the railway tracks, and Neulengbach, where he was imprisoned, and found his prison cell.

Most exceptionally, Alessandra interviewed and photographed Gertrude Schiele and Adele Harms, the only two muses then still alive. She sent me the recordings, which was exceptionally exciting. Unfortunately, I don’t speak German, but I heard the tones of their voices and how haughty Adele still sounded. Alessandra confirmed to me that she had this very posh Viennese accent.

Adele told Alessandra she had an affair with Egon Schiele. It had been hinted at in some of the books that I’d read, but to hear it from someone who heard it from Adele directly was very intense.

Egon Schiele, Reclining Woman with Green Stockings (1917). The model for the work was the artist’s sister-in-law, Adele Harms. Private collection.

Alessandra and I discussed it, and decided “affair” could have two or three different meanings. It could be that Egon Schiele courted both the sisters at the same time, that he wasn’t sure which he was going to choose for his wife. Or Adele might have meant that they had a physical sexual relationship, either before or after he married her sister.

We also thought there might have been some element of delusion there. Adele might have misremembered, she might have embellished. She might have wanted this intense relationship with this man.

When I looked at Seated Woman With Bent Knee again, I saw all this longing and desire and regret in her eyes. And I wondered if perhaps she had felt more for her sister’s husband than the history books recorded. Had she imagined more to their relationship than was truly there?

How much evidence is there that Adele struggled with mental health issues?

There’s not very much recorded about her after Egon and Edith die. I went through the records at mental health facilities in Vienna, but I couldn’t find anything. When I went to Vienna for research, I met the Schiele historian Christian Bauer. He told me Adele died in Vienna at age 78, penniless and practically living on the streets. She’d never married or had children. It sparked so many questions.

I just imagined her as this young woman, beautiful, well educated, from a well-to-do family. She had the whole world kind of at her feet, but her life was thrown off course. The death of her sister must have rocked her mental health deeply.

The first World War had decimated Vienna, and then there was the Spanish influenza pandemic. Adele would have come out at the other side of that alone. Grieving. No money, no real skills with which to put herself to work. I just couldn’t imagine her ever getting back on her feet after that trauma.

Egon Schiele’s story stops in 1918. But I couldn’t stop thinking about this woman who was living in the aftermath.

Egon Schiele, Woman in Underwear and Stockings (1913). The model for the work was Walburga “Wally” Neuzil. Collection of the Leopold Museum, Vienna.

There’s often a sense, especially in the art world, that there’s only room for so much female success—that women are in competition rather than being able to support each other. Did it trouble you at all, narratively, to have your four female characters as rivals? I

think so. Rivalry between women is learned and is problematic. Women do feel pitted against one another for male attention. That’s certainly something I observed in my early 20s. Wally was only 17 when she met the artist, and the artist himself was such a young man. I think telling the story of them in their thirties, there would’ve been far less of that kind of drama.

But from what I could tell, Edith was threatened by Wally and how popular her artwork had been. And Wally was definitely upset that she’d been discarded for another woman. These were real dynamics that existed between them.

Egon Schiele, Bildnis Wally Neuzil (1912). Collection of the Leopold Museum, Vienna.

I couldn’t believe that the letter that Wally finds in the book, in which Schiele says “I intend to marry advantageously, (not Vally),” and the pledge she signs saying she is not in love with anyone in the world, that those are both real. And Schiele actually drew up a contract for her to spend two weeks with him each year after his marriage, which she rejected!

Isn’t that incredible? The word for me that always comes up with is value. Egon Schiele doesn’t see Wally’s true value, and he doesn’t appreciate her true worth, and she gets discarded. I would’ve loved to see her kind of thrive in a world without him. It’s such a tragedy that she dies so soon after she leaves him, in such sad circumstances. She had all the ingredients to live a very dynamic, very fulfilled, very unconventional life. But she didn’t get the chance.

Egon Schiele, Seated Female Nude With Raised Right Arm (1910). The model for the work was the artist’s sister, Gertrude Schiele. Collection of Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien.

Do you have an opinion about whether or not Egon and Gertrude had an incestuous relationship?

I think it’s impossible to answer. My book doesn’t give a firm answer of whether they had sex or not. That’s a very deliberate part of the book. The main questions for each woman were, did he sleep with Gertrude and did he sleep with Adele, and did he love Wally and did he love Edith?

With Gertie, I think he adored her and I think she adored him and I think their relationship was intimate and I think it was complicated. There is some implication in the book that when she’s pregnant, it’s with Egon’s child. And that’s why she has to marry Anton. I don’t think she had her brother’s baby, but the question of whether that’s possible is central to their relationship.

Do you feel any potential guilt for writing about Schiele, any concern that maybe he was in some way a sexual predator or exploiting these women, especially considering the obscenity charges he faced in his lifetime?

Exploit is a very heavy word, but I think Schiele was ruthless in his ambition. And I think he was prepared to sacrifice all his most precious relationships in order to become a great artist. I think he knew what a woman could give him, and what he could get from a woman. And I don’t think he felt much guilt when he moved on.

And it’s a fine line when you’re a young artist trying to shock society and break boundaries. I think the experience of going to prison and being incarcerated for 24 days really changed him. I really feel for Tatiana [the girl that Schiele was charged with but found not guilty of kidnapping]. She might have found herself embroiled in something that was bigger than her and was beyond her control.

Egon Schiele, Seated Woman, Back View (1917). The model for this work was the artist’s wife, Edith Harms. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In the book, the incident is presented as a misunderstanding. Do we know if she was being asked to pose for Schiele in inappropriate ways, or if there was any evidence of a sexual relationship?

I couldn’t find any specific artworks that depicted her without her clothes on. The charge that was upheld for him was that minors saw erotic artwork in his home. But you could tell this story in so many ways.

I spoke to Jane Kallir [head of New York’s Kallir Research Institute and author of Schiele’s catalogue raisonné], and she takes a very firm line that Egon Schiele was not a pedophile. Egon Schiele and Wally did spend the night in Vienna with Tatiana. Her father charged that his daughter had been kidnapped and supposedly seduced. Jane’s opinion is that certainly wasn’t the case. And I took her guidance on that. It seemed to fit with who I believe Wally to be.

Egon Schiele, Portrait of Edith (the artist’s wife) (1915). The model for the work was the artist’s wife, Edith Harms Schiele. Collection of the

Gemeentemuseum Den Haag in The Hague.

What does it mean to you to tell Schiele’s story from the point of view of his muses?

In a way, they get to paint this kind of portrait of the artist. I wanted to create that reversal. It’s a portrait that shifts and changes over the course of the book. You get a slightly different view of him when you’re seeing him through Gertie’s eyes or his wife’s eyes. And it’s one that, like Schiele’s artwork, is not always sympathetic. It’s not always beautiful. It’s often challenging. It can be grotesque. But it’s not shying away from who these women might have been and what their stories might have been.

How important was it to revive the names of these four women who have been completely overshadowed in the annals of earth history?

I really wanted their names to be attached to their faces, for people to be able to look at these famous portraits that Schiele made and to know who these women were—for them not to be forgotten.

Lots of readers have told me once they finish the book, they go off and they look for these women’s stories. And that, for me, is the dream.