They cut holes into the floor for years, turned the basement into a pseudo Victorian theater, and even demolished and rebuilt the storefront. But the only time the staff of the Los Angeles alternative space Machine Project had trouble with the landlord was when they rented the apartment above to host visiting artists and cut a trap door through the ceiling to connect the two spaces. They paid to repair the damage, which was not too steep a price, “considering the things we did to the building,” marvels Mark Allen, Machine’s founder.

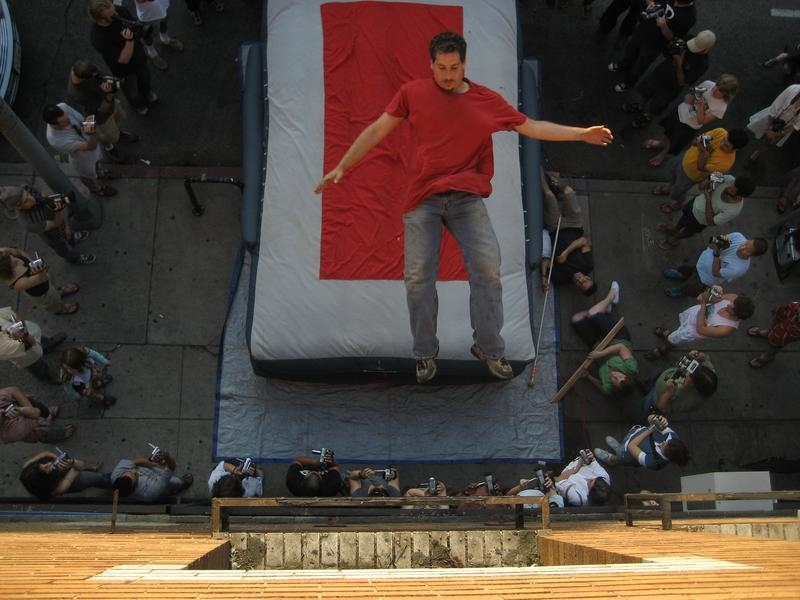

Over the past 15 years, that building—a former skate shop on busy Alvarado Street in Echo Park—has become a laboratory for interdisciplinary experiments by emerging artists, poets, and a host of others in the local art community as well as a model for alternative spaces across the country. But this month, Machine Project is closing its doors for good.

“I wanted to think of it like an arc, as a completed project,” says Allen, who planned for the closure for a year, feeling that Machine had run its course. True to form, however, it is not exiting quietly.

The debut of Machine’s basement Mystery Theater in 2014. Image courtesy of Machine Project.

As a final contribution, Allen teamed up with a small group of collaborators to assemble four “toolkits,” which are available online for free today. These guides attempt to make 15 years’ worth of alt-space knowledge transferable, to aggregate unconventional institutional memory and make ventures that are often fly-by-night a little less intimidating. This exercise is particularly valuable at a time when rapidly rising rent in many major cities makes starting something new less accessible, and growing wealth gaps in the country and the art world in particular make alternative platforms all the more needed.

The Machine Project Guide to Starting Your Own Art Space, which grew out of a workshop Allen began giving around six years ago called “DIY Art Space or Whatever,” lays out options for how to get started, from setting up a physical space to launching a nomadic program to hosting a project in your own home. “There are many ways to try to change the world,” Allen writes optimistically. “Starting an art space” is a “good start.”

The toolkits tackle everything from the practical to the existential: how to curate events, host workshops, build a board, make financial decisions, and, in the final toolkit, make butter while doing aerobics. (This last chapter, indicative of Machine’s tendency to push a gimmick so far it becomes somehow serious, includes the advice, “pummel that cream into submission.”)

The inaugural “Butter Aerobics” class, organized and taught by Jimmy Fusil and Mike Wait at Machine Project (2012). Image courtesy Machine Project.

Meldia Yesayan, Machine’s managing director, compares reading the toolkits to “going to a scientific journal to research the result of a specific experiment.”

Disbursing this knowledge is also a way to make Machine’s closure generative rather than an apparent failure. “I wanted to make a demonstration that you could close a non-profit. You didn’t have to run it forever,” Allen says. “We don’t judge people as failures because they die,” he adds. “It’s kind of inevitable.”

The finished toolkits, cheerily designed by Tiffanie Tran and Rosten Woo, never frame Machine’s way as the only way. But they offer valuable advice for enterprising, idealistic art collectives and organizations, from those seeking non-profit status to those content to operate out of a studio apartment.

Here are eight approaches that emerged from the toolkits, and insights from local artists and organizers who have already been inspired by Machine.

1. Go do some stuff.

This is the most common refrain throughout the toolkits. Don’t get stuck under the weight of first-time pressure, Allen suggests. Instead, begin “doing by doing”—even if your first attempt is small or temporary. Allen first put this tenet into practice during Machine’s inaugural event in 2003, a 20-minute closed-door concert with animated projections by artist Kelly Sears. It started at exactly 10:21 p.m. No one who arrived even a second late could get in. “It was a fun event, but not necessarily one for the ages,” Allen writes. “My goal wasn’t to orchestrate the perfect experience; it was to pick something to do, find people to do it with, and do it.”

2. Create context for what you want to see in the world.

Running an alternative space, especially a decidedly experimental one, isn’t for the faint of heart. That’s why Allen says it’s worth asking: “Why are you doing this again?” His motivation: to fill the world with what interests him. And while others may have different missions, they probably want to see more of something, too (even if just more of their friends’ art).

Sarah Bay Gachot, who started the monthly event series Stupid Pills with her partner Paul Gachot in 2012, remembers the first event she attended at Machine, which involved an experiment with remote control Madagascar cockroaches. “I was blown away,” she says. This experience, among others, helped inform the mission of Stupid Pills, which aimed to give artists a platform to do something they don’t normally do.

Installation view of Joshua Beckan’s Sea Nymph (2010) at Machine Project. Image courtesy of Machine Project.

3. Stay flexible.

Your interests—and objectives—may change. Early on, Machine filled the world with one-off experiences, like electronic workshops and experimental poetry. Later, it brought those experiences into museums, and its storefront became a space where artists created ambitious, long-term projects. The artist and playwright Asher Hartman, for example, developed three experimental plays that required months of rehearsals, extensive fundraising, and extreme architectural alterations. Machine’s willingness to invest time and money in his creative output—whatever it might be—“took some of the fear of what is right and wrong out of the practice of making art,” Hartman says.

4. Set a tone.

Since the beginning, when its email list was small, Machine aimed to strike a friendly but slightly awkward tone when reaching out to its community. It was “the voice of an organization called Machine that would sign an email with ‘love,’” recalls Allen. Audience members who found this compelling paid attention—and, in some cases, became important contributors to the organization.

5. Trust your audience to get it (even if you don’t always get it yourself.)

Artist Anna Mayer, part of the duo CamLab, took inspiration from Machine as she and her collaborator, Jemima Wyman, began staging interactive performances. “Machine insisted that you could ask a public, not just your peers, to undertake something experimental, transient, or destined for failure with you,” she recalls. Throughout the guides, Allen reminds readers to give audience members space to develop their own relationship to a program and not dictate their experience. “It’s just disrespectful […] to decide for them that something is boring, bad or dumb,” he writes.

6. Work with people you like.

Sarah Williams, co-founder of the non-profit Women’s Center for Creative Work, took Allen’s “DIY Art Space” workshop well before she knew she would found her own organization. Years later, when it came time to put together a board, she met with Allen and Yesayan for lunch at Machine. They gave her permission to say no to potential members, which she found liberating. “Mark told me, ‘If you don’t want to hang out with someone, don’t ask them to join,’” she recalls.

In the toolkits, Allen takes this idea even further: Never do a project as a favor, he advises. When deciding to take on a major project with an artist, he asks himself two questions: “Do I like them personally?” and “Do I think their work is interesting and worthy of a wider audience?”

Asher Hartman’s play Sorry Atlantis: Eden’s Achin Organ Seeks Revenge (2017), performed on Machine Project’s raised floor. Photo: Agnes Bolt, image courtesy Machine Project.

7. Make clear choices about cultural capital.

The email Allen sent out to announce Machine’s very first performance buried the name of the artist, Kelly Sears, beneath other promises for the event: “prog rock video with live guitar and bass shred. Bud Light keg beer. Also kittens.” Throughout its life, Machine never front-loaded the name of the talent in its announcements—the content of events took precedence. “Personally I subscribe to the concept of singular authorship as pernicious wraith—an annoying ghost that haunts galleries and institutions,” Allen writes. “You can bust this ghost by putting the work first.”

8. Allow for chaos and ambiguity. (Invite it, even.)

Early on in the Guide to Starting Your Own Art Space, Allen admits that Machine’s often-ambiguous mission and amorphous identity came at a cost. For one thing, larger grant-giving institutions often passed it by. One refused Machine because it was deemed “too experimental to scale.” Another institution canceled an already-underway, collaborative public art series because of “questionable artistic quality.” But Allen maintains these setbacks are useful for any organization that wants to do unorthodox work. “Failure,” he writes, “yields useful data.”