When it came to 18th-century New York City society, Elizabeth Schuyler was undeniably a member of the upper crust, daughter to one of the city’s wealthiest and most politically influential families, and wife to none other than founding father Alexander Hamilton.

Today, she is enjoying renewed fame, thanks to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Grammy- and Tony-winning Broadway musical, Hamilton, which reveals her sometimes-troubled relationship with the title character. If you want a glimpse of what Schuyler Hamilton was really like however, it’s worth taking a trip uptown, to the Museum of the City of New York (MCNY), where her portrait is on view as part of “Picturing Prestige: New York Portraits, 1700–1860.”

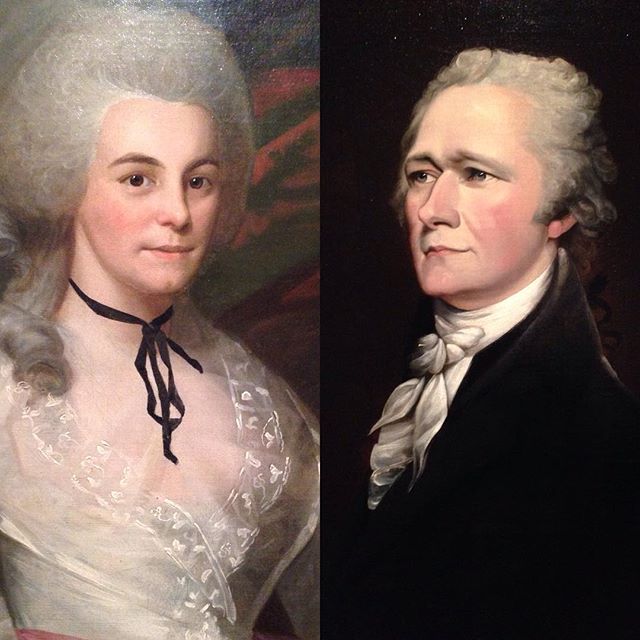

Hung next to the instantly-identifiable image of her spouse painted by John Trumbull (a posthumous 1805 portrait that appears on the $10 bill) is an elegant portrait of Schuyler Hamilton from 1787. She’s outfitted in a diaphanous white gown with a bold black ribbon tied around her neck, but the backdrop of rich scarlet tapestries conceals an ugly truth: In order to have the portrait made, Schuyler Hamilton had to make a visit to the local prison, where the artist, Ralph Earl, was incarcerated due to his debts.

Strange as it may seem, there were very few artists to be found during the early years of our country, and Earl’s services were in high demand even as he languished in debtors’ prison at City Hall.

“He was really the only trained portrait painter in the city at this time,” said Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, the curator of American painting and sculpture at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art at “Hamilton and Friends: Portraiture in Early New York,” a program held earlier this month at MCNY.

Early New Yorkers, eager to show off their wealth and stature by sitting for a portrait, suffered from periodic droughts of artists.

John Trumbull, Alexander Hamilton (1792).

Photo: courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1771, for instance, John Singleton Copley spent six months in New York, and completed no less than 37 works for the city’s portrait-starved citizens. “He was besieged with commissions,” added William Gerdts, a professor emeritus of art history at New York’s CUNY Graduate Center.

Nevertheless, that a woman of Schuyler Hamilton’s import and class would be willing to enter a prison to have her picture painted is quite remarkable. “The prison conditions were horrific,” said Kornhauser, who suspects Earl would have had a separate studio space, perhaps funded by the Society for the Relief of Distressed Debtors. “There’s no way I could envision him seated in this hideous environment, painting this highly important member of New York City society.”

The exhibition spans the late colonial period to the latter half of the 19th century, and includes portraits of New York city elite from George Washington to members of the Brooks family, of Brooks Brothers fame.

Portraits, said panel moderator and MCNY painting and sculpture curator Bruce Weber, allowed “New Yorkers of prominence to craft their public image” much the way social media and selfies work for people today. (The exhibition hashtag is the tongue-in-cheek #unselfie.)

John Wollaston, Mary Crooke Marston.

Photo: courtesy the Museum of the City of New York.

For some, that might mean subtle references to success in their profession, such as Mary Crook Marston’s outfit of costly Chinese satin, as seen in her pre-Revolutionary War portrait by John Wollaston. A matching painting of her husband, Nathaniel, shows him writing “Canton” in his ledger, in reference to his successful trade in China.

In the years immediately following the war for independence, however, the American elite turned to simplicity, eschewing the fripperies of the British aristocracy in favor of portraying their patriotism and civic virtue.

An earlier Hamilton portrait by Trumbull, co-owned by the Met and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, was, per the sitter’s request, utterly lacking in vulgar displays of wealth or deeds. Despite Hamilton’s significant political and military achievements, “there is nothing emblematic of his accomplishments” in the 1792 painting, said Kornhauser.

That portrait was actually commissioned by the city government, as the young nation attempted to forge its new identity. It was displayed, alongside paintings of Washington and other leaders, at City Hall, where the portrait gallery, unlikely as it might seem, acted as Manhattan’s first art gallery.