The heirs of Jewish art collector Max Emden are suing the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, for the return of Bernardo Bellotto’s Marketplace at Pirna (ca. 1764), which they claim he sold under duress to an art buyer for Adolf Hitler in 1938.

The suit, filed last week in the Southern District of Texas’s Houston Division, is being brought by Emden’s grandsons, Juan Carlos Emden, Nicolás Emden, and Michel Emden. It contends that “Emden was a victim of the ‘handiwork of evil,’ the Nazi regime’s systematic persecution of European Jews,” and that his heirs are the work’s rightful owners.

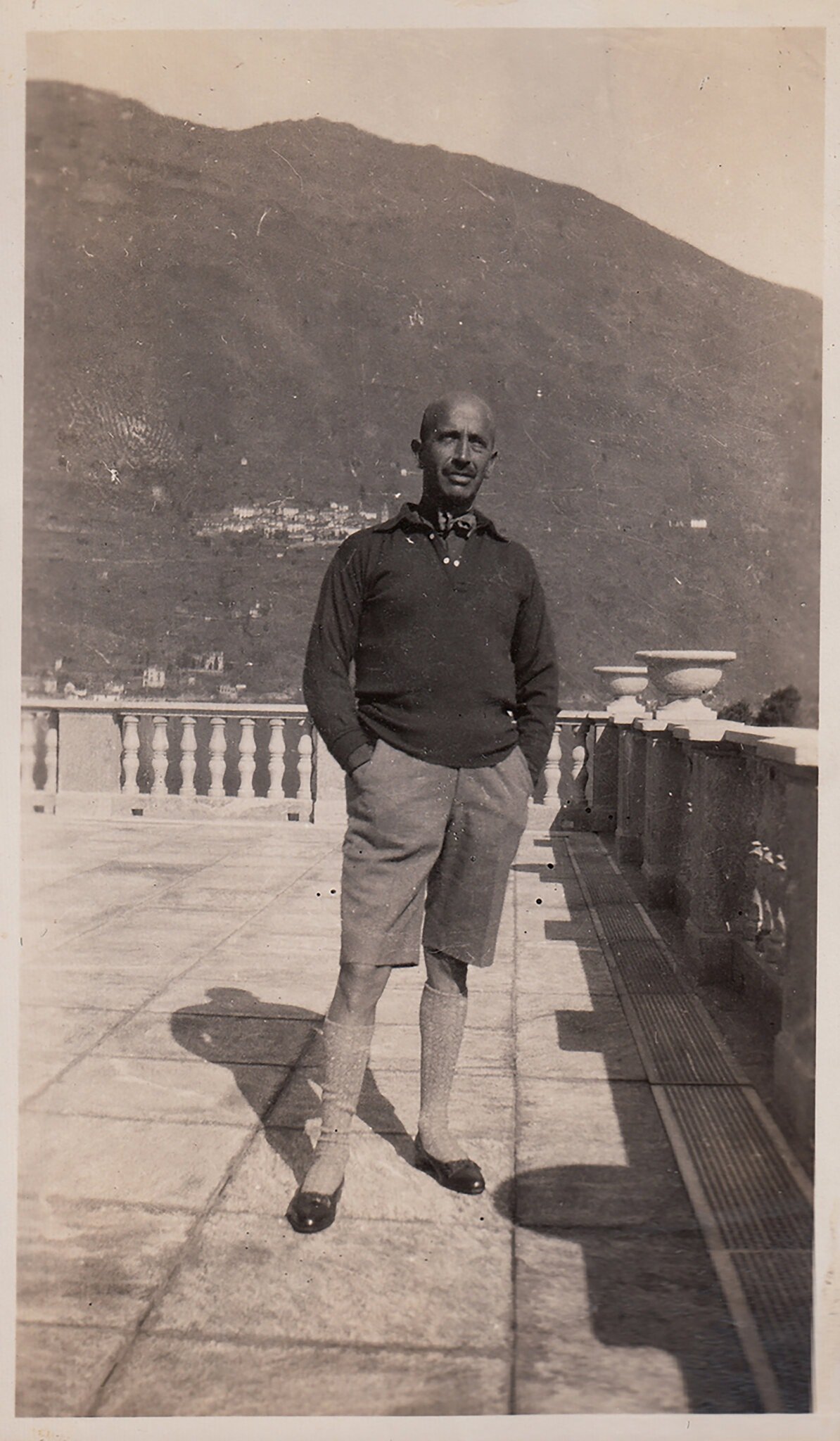

Emden moved to Switzerland in 1927, but still owned a textile trading company in Berlin and had German bank accounts. As the Nazis implemented a policy of “Aryanization,” his assets were frozen, and his company was eventually liquidated.

As his financial situation deteriorated, Emden engaged the dealer Anna Caspari to offload three Bellottos, including Pirna. After seven and a half months of negotiations, she sold them to Karl Haberstock, a German art dealer, who the same day sold the works to the Reichskanzlei (Reich Chancellery) for the Führermuseum.

Bernardo Bellotto, The Marketplace at Pirna (ca. 1764). Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Emden’s heirs argue that the selling price, SFr. 60,000 ($13,755, or $4,585 per painting), was well below market value, citing a letter from Caspari to Haberstock in which she noted that “we have just caught the right psychological moment, [Emden] has probably lost a lot on the stock exchange and would therefore accept this price,” and that just one of the works was probably actually worth “a much higher price than the purchase price for all three.”

The museum disagrees. “The historical evidence establishes that this painting was not the subject of an unlawful appropriation,” a spokesperson told Artnet News in August. “Max Emden, who was living on a private island in Switzerland, initiated the sale of and sold his Bellotto paintings at a fair-market price though his dealer of choice.”

The Emdens’ case, however, appears to be bolstered by the fate of the two other Bellottos, which were restituted to his family in 2019. A ruling from the German Advisory Commission found that the sale was “not undertaken voluntarily but was entirely due to worsening economic hardship (‘loss of assets as a result of persecution’).”

The MFAH Bellotto might have been restituted at the same time, were it not for an clerical error by the Allied Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Unit, also known as the Monuments Men, which recovered the paintings in 1945 from an Austrian salt mine hiding thousands of artworks Hitler planned to show at his unrealized Führermuseum.

The three works were ultimately separated. Two went to Germany, but the MFAH Bellotto went to the Netherlands. By the time the Monuments Men realized the error and asked for it back, the Dutch government had already mistakenly restituted it to Hugo Moser, a German art dealer living in New York.

The confusion arose because Moser purchased a copy of The Marketplace at Pirna at a Berlin auction in 1928 that he left in Amsterdam when he fled to the U.S. Dealer Maria Almas-Dietrich—known for acquiring copies of major paintings rather than the real deal—purchased the work for the Führermuseum in 1942, but she never delivered it to the Nazis.

A photograph of Bernardo Bellotto’s The Marketplace at Pirna (ca. 1764), taken by art dealer Karl Haberstock after he bought it from Jewish collector Max Emden for Adolf Hitler, shows a faint inventory number in the corner from former owner Gottfried Winkler. Photo courtesy of the Monuments Men Foundation.

The Monuments Men confiscated her collection in 1945 and brought it to the Munich Central Collecting Point, where the Emden Bellottos later joined it. The organization identified Moser’s painting as a copy of a Bellotto composition by an unknown artist and catalogued it as such.

Then the Dutch government reached out, asking for the return of Bellotto’s The Marketplace at Pirna, not realizing the work it was seeking was not actually the original. The Monuments Men accidentally sent the Emden Pirna to the Netherlands instead of Moser’s copy. (Recent research by Monuments Men Foundation, which is aiding the Emdens in their restitution quest, helped untangle the complex details of what actually happened surrounding the two versions of The Marketplace at Pirna.)

When Moser received the painting, he created a new provenance for the work and sold it to the American collector Samuel H. Kress 1952. Kress arranged a long-term loan of the painting to the MFAH in 1953, and donated it outright in 1961.

Had Moser’s Pirna copy not muddied the waters, however, the MFAH Bellotto would have likely stayed in Germany, and be subject to the 2019 restitution ruling.

“While we respect the decision of the German panel, their decision does not alter the fact, established from extensive research, that the 1938 sale of this painting was voluntary,” the museum spokesperson said.

But even if Emden did not sell under duress, however, the museum’s legal claim to the work remains unclear. Moser was never the Bellotto’s rightful owner, so it follows that he could not transfer good title to Kress, even if Kress purchased the painting in good faith.

That’s part of the Emdens’ argument. “The museum’s assertion of clear title is horrific given that it emanates from the Nazi government’s ‘purchase’” of the work, the suit attests.

The Emdens are seeking the work’s return, plus legal fees and damages.