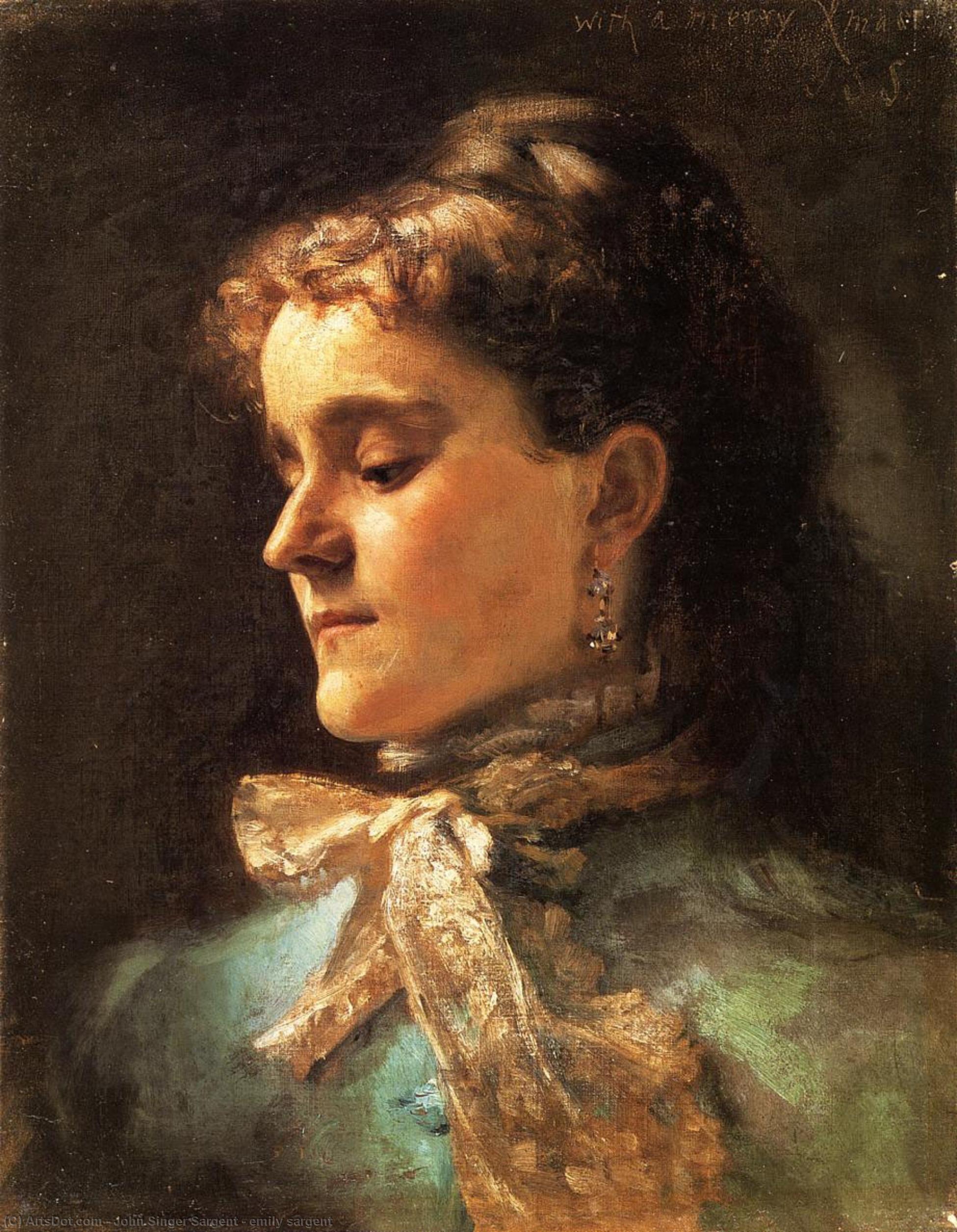

John Singer Sargent is well known as perhaps the most famous portraitist of the late 19th and early 20th century, and a prolific master of watercolor who captured over 2,000 views of landscapes all over the world. But what few people realize is that for years, his sister Emily Sargent painted alongside him, creating a significant body of work that has almost never been seen—until now.

Until last year, Emily Sargent’s talent had remained something of a family secret. A few of her paintings hung in relatives’ homes, and those in the know realized that she could be seen in several of John’s watercolors, at work at an easel of her own. But the full scale of Emily’s practice only became clear in 1998, when a family member discovered a forgotten trunk containing a stash of 440 of her watercolors.

“It was rather like a revelation,” Richard Ormond, Emily and John’s great nephew, told Artnet News. “All these wonderful paintings were there, fresh as a daisy, of course, because they’ve been kept away from the light!”

“We all knew she was an artist,” he added. “But with this discovery, suddenly you realized she was a really dedicated artist—and a very original artist. It opened all our eyes to the fact that Aunt Emily was not just an occasional amateur, but a really serious artist.”

John Singer Sargent, In the Generalife (1912). Emily Sargent can be seen at her easel in this painting of gardens of the Generalife palace at the Alhambra in Granada, Spain, with fellow artist Jane de Glehn (left) and friend Dolores Carmona (right). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

It took nearly 25 years, but the Sargent family has finally begun sharing the contents of that trunk with the world, quietly arranging in 2022 to donate a massive cache of Emily Sargent’s work to a selection of museums in both the U.S. and the U.K.

The family is potentially arranging one or two additional gifts of Emily’s work, but Ormond’s hope is that the majority of what is left can stay together, perhaps at some kind of Emily Sargent Center dedicated to her life and career.

“I don’t think we want to sell them,” he said. “If we could find just the right sort of place to keep them together, that would be ideal.”

Emily Sargent, View of Constantinople (1904). Collection of the Tate, London.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, got the lion’s share, with 45; followed by 29 to the Tate, London; and 24 to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. In New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art got 22 and the Brooklyn Museum got 20. Rounding things out were the Ashmolean at Oxford University, with 19, plus 15 to the smallest institution on the list, the Sargent House Museum in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where the Sargent siblings’ ancestors lived.

“There was a feeling among the family that we ought to do right by Emily by distributing some of her works to museums that already had Sargent connections,” Ormond said, noting that if they had tried reaching out to institutions back when the works first turned up, there probably would have been fewer takers, considering the recent rise in interest in overlooked women in art history.

Emily Sargent (ca. 1910). Photo courtesy of the Richard Ormond.

“It makes a lot of sense to add works by Emily to our Sargent collection,” Stephanie Herdrich, the Met’s associate curator of American painting and sculpture, told Artnet News. “It was very exciting to be invited to choose a selection of work by Emily for the collection. Some of them relate directly to works by John that we already owned, including an instance where she had painted the exact same composition as him!”

The museum has actually been the recipient of multiple gifts by the Sargent family over the years, including a donation in 1950 largely comprising more informal works on paper, which basically represented the last remnant of the estate. But despite John Singer Sargent’s renown during his lifetime—his last show, just a year before his death, attracted 60,000 people in just 44 days—the artist fell out of favor in the decades that followed.

Attributed to Emily Sargent, Spain. This work was among the remnants family estate donated by Emily and John Singer Sargent’s younger sister, Violet Sargent Ormond, in 1950. Years later, art historians determined the work was likely by Emily, not John. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

“In the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, no one was paying much attention to Sargent and his reputation was not great,” Herdrich said. “It wasn’t until the 1990s that we even catalogued everything thoroughly.”

That’s when the museum realized there was more than one hand at work in that last gift. There was a sketchbook by the family’s mother, Mary Newbold Sargent (née Singer), plus a selection of watercolors that curators now believe are by Emily.

Born in 1857, Emily Sargent suffered a serious spinal injury at just four years old, which was exacerbated by a period of prolonged immobilization. Despite her lifelong frailty, she traveled extensively, immortalizing such diverse places as Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Tunisia, Palestine, and Egypt in her work.

“She’s got a great feeling for the atmosphere of places, and she conjures up a sort of world,” Ormond said. “She’s quite decisive in the way she handles the paint. She’s not timid—she’s quite bold, with strong colors and contrasts, and a great range of styles.”

Emily Sargent, Pergola at the Villa Varramista (1908). Collection of the Tate, London.

The Sargent children grew up overseas, their parents finding it more affordable to travel across Europe than to remain home in the U.S. It was their mother who insisted they all learn to paint and draw.

“There are these stories that their mother encouraged all of the children to finish at least one sketch every day,” Herdrich said. “But the family only sent John to art school. They invested in his professional education. Emily didn’t have those opportunities in the 19th century.”

After her early tutelage, Emily seems to have set aside art until her 30s, after the death of her father in 1889. The majority of her extant work dates from the year 1900 or later, a period when she began traveling extensively with her brother on his European painting exhibitions. But after its creation, Emily’s art stayed close to home.

Emily Sargent, Chatriali, near Biskra (1902). Collection of the Brooklyn Museum.

“Emily was too modest, like many ladies of her time, to think of ever exhibiting or selling her work. That prejudice against a woman being a professional was still strong,” Ormond added. (She showed her work only once, contributing a few Old Master copies to a group exhibition the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1908.)

Neither John nor Emily ever married or had children, and the two remained quite close throughout their lives.

“Emily acted almost like a de facto wife, hosting parties for him, helping to promote his work, and sell it to collectors,” Herdrich said.

Their third surviving sibling, Violet Sargent Ormond, was much younger, born 13 years after Emily, who was in turn a year younger than John. Violet ultimately had six children, six grandchildren, and at least 15 great-grandchildren.

Emily Sargent. Photo courtesy of the Sargent House Museum, Gloucester, Massachusetts.

Ormond was born in 1939, the youngest of child of Violet’s youngest son, and never got to meet his great-aunt or -uncle, who died in 1936 and 1925, respectively. But he’s become a leading scholar of John’s work, authoring numerous books on the artist, including a nine-volume catalogue raisonné, and curating shows such as “Sargent in Spain,” which debuted last year at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and travels next month to the Legion of Honor at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Now, Ormond is turning his attentions to Emily Sargent, researching her heretofore unsung life through the correspondence of her family and friends, as well as through existing John Singer Sargent biographies. What he sees is a figure ripe for her own moment in the spotlight.

“I’d love for somebody to do a major, proper exhibition of her work—or even to write her up, as she’s an interesting personality in her own right,” he said. “She’s not simply the sister of a famous man, and her art is not is not simply a pale reflection of John Singer Sargent. She’s quite got her own style, her own way of painting.”

“Emily Sargent, A Glimpse Into Her World,” installation view at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy of the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Massachusetts.

Already, there’s a small exhibition of Emily Sargent’s paintings that opened last fall at the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester, courtesy of loans from the Sargent House while it is closed for the offseason.

It is the first-ever solo show of the artist’s work, featuring one of the newly donated Emily Sargent works, as well as a quartet of pieces donated by the Sargent sisters during their lifetimes. Their cousin Charles Sprague Sargent opened the museum in 1919, and John and Emily were among the visitors to the inaugural exhibition.

The Cape Ann show offers a small taste of what’s still to come at a larger exhibition the Sargent House plans to open in June, drawing both on her work and letters in the family archives, held by the MFA.

Emily Sargent copying an Old Master painting at the National Gallery, London (ca. 1930). Photo courtesy of Richard Ormond.

“In Emily’s writing, you really see how funny she is, and interested in current events. It’s fascinating to go deeper into her life,” Jen Turner, the Sargent House curator, told Artnet News. “And she wrote about taking her supplies every day and going off to paint in the afternoons. It gives you a vivid sense of who she was as a person, and how much her art really meant to her.”

“It’s really exciting that a museum that’s connected to the Sargent family will host the first major American museum show that will deal with Emily Sargent’s material exclusively, and talk about her life, her world,” Turner added. “We’re really looking forward to giving Emily her day in the sun, showcasing her story and her talent—which is pretty impressive for someone who never went to art school.”

Emily Sargent, Untitled (Tropical Seascape). Collection of the Sargent House Museum.

The curator is also preparing a talk at the Cape Ann for March 25, comparing Emily Sargent to her great-great aunt Judith Sargent Murray, the original occupant of the home. Like Emily, Judith had a celebrity brother: Winthrop Sargent, a patriot who served in the American Revolution and as the first governor of Mississippi territory. But Judith was a remarkable woman in her own right; an early advocate for women’s equality and prominent essayist.

“These were both educated women who had more famous brothers,” Turner said. “Emily was a talented woman and a talented artist, and she and Judith both deserve to be seen in their own light.”

Other museums are poised to help in that effort. The Met, for instance, is hoping to showcase Emily during a 2025 show about John’s time in Paris, and to work with the curators at the other museums that are the recipients of her work to develop scholarship about her previously unrecognized career.

“It’s all kind of new, and we’re on this journey of discovering Emily and putting her kind of at the center of the story as opposed to a character in John’s life,” Herdrich said. “Hopefully we can bring her out of the shadows.”

“Emily Sargent, A Glimpse Into Her World” is on view at the Cape Ann Museum, 27 Pleasant Street, Gloucester, Massachusetts, November 29, 2022–May 7, 2023.