Writer and illustrator Eric Carle, the author of the classic children’s picture book The Very Hungry Caterpillar (1969), died on May 23 at age 91. He was at his summer studio in Northampton, Massachusetts.

The cause of death was kidney failure, with Carle continuing to draw until this month, according to the New York Times.

Over the course of his career, Carle published more than 70 works, selling more than 170 million copies of titles such as The Very Busy Spider (1984) and Papa, Please Get the Moon for Me (1986) in dozens of languages.

But no book was more popular than The Very Hungry Caterpillar—55 million copies sold and counting—in which the increasingly ravenous title character eats its way through the story before spinning itself a cocoon and transforming into a vibrantly colored butterfly.

Some of the illustrations from Eric Carle’s children’s book The Very Hungry Caterpillar. Courtesy of Penguin Young Readers.

In an innovative approach, Carle designed the book so that the caterpillar literally eats its way through.

“It all started innocently with a hole puncher. I was punching holes into a stack of paper and I thought of a bookworm, and so I created a story called A Week With Willi the Worm,” Carle told Scholastic on the book’s 45th anniversary.

“Then later, my editor who didn’t like the idea of a worm, suggested a caterpillar, and I said, “Butterfly!,” and the rest is history.”

Eric Carle and his longtime editor, Ann Beneduce, at the 2016 Carle Honors in New York. Photo by Johnny Wolf photography, ©Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art.

Bringing that vision to life was a challenge due to the high costs of manufacturing such a book. But when U.S. printers rejected the project, Carle’s editor, Ann Beneduce, who died in March at 102, found a printer willing to take on the task in Japan.

Over the years, Carle developed a theory as to what was behind the book’s lasting appeal.

“It’s a book of hope. That you, an insignificant, ugly little caterpillar can grow up and eventually unfold your talent, and fly into the world,” he told Metro in 2009.

“As a child, you can feel small and helpless and wonder if you’ll ever grow up. So that might be part of its success. But those thoughts came afterwards, a kind of psychobabble in retrospect.”

Carle was born June 25, 1929, in Syracuse, New York. His parents were German immigrants, and he was six when they returned to their native Stuttgart, where Carle grew up under the Nazi regime, witnessing the horrors of World War II. He was conscripted to dig trenches at age 15, and spent time living with a foster family when the town’s children were evacuated.

“During the war, there were no colors,” Carle told NPR in 2007. “Everything was gray and brown.… Houses were camouflaged with grays and greens and brown-greens and gray-greens or brown-greens.”

On long walks with his father, who was drafted into the German forces and imprisoned for two years by the Soviets, Carle developed a love for nature that would later infuse his work.

Eric Carle The Very Busy Spider. Courtesy of Penguin Random House.

“When I was a small child, as far back as I can remember, [my father] would take me by the hand and we would go out in nature,” Carle told the New York Times in 1994. “And he would show me worms and bugs and bees and ants and explain their lives to me. It was a very loving relationship.”

A high school teacher, Herr Kraus, introduced him to Modern art, secretly showing Carle works by the German Expressionists, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Klee, and other artists who had been deemed degenerate by the Nazis.

“At first I was upset. I thought, this man is crazy because I’ve never seen anything like this,” Carle admitted. “He believed in my artistic development… That’s why he felt I should see it. Also he had enormous trust in me that I would not turn him in. That man had an enormous influence on me by showing me that type of work.”

Today, Carle is known for his instantly identifiable style of boldly colored tissue paper collage, made using wallpaper glue on illustration board.

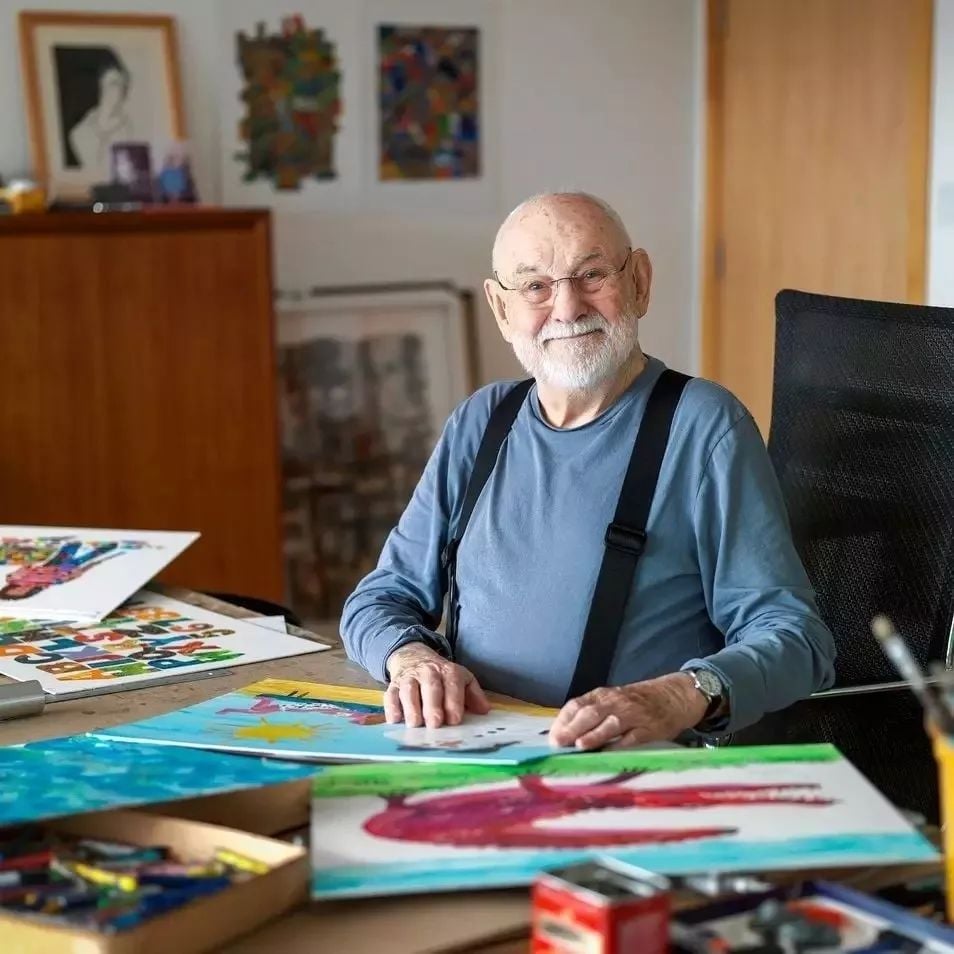

Children’s book author Eric Carle photographed in his North Carolina studio in 2015. Photo by Jim Gipe, Pivot Media, ©Eric Carle Studio.

“I begin with plain tissue paper and paint it with different colors, using acrylic paint,” the artist wrote of his process on his website. “Sometimes I paint with a wide brush, sometimes with a narrow brush. Sometimes my strokes are straight, and sometimes they’re wavy. Sometimes I paint with my fingers. Or I put paint on a piece of carpet, sponge, or burlap and then use that like a stamp on my tissue papers to create different textures.”

“The style was quite revolutionary,” children’s illustrator Jane Ray told the Guardian. “It was part of a whole new movement in children’s illustration and it really set the tone for what was to come.”

Carle studied at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Stuttgart. Two years after graduating in 1950, he returned to the U.S., making a living as a commercial artist in the advertising business, including as a graphic designer for the New York Times.

His first foray into children’s books came in 1967, when Bill Martin Jr. hired him to illustrate his book Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? The duo also partnered on three sequels.

Eric Carle’s first picture book was Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? by Bill Martin, Jr. Courtesy of Henry Holt and Co.

“While waiting for a dentist appointment, I came across an ad [Carle] had done that featured a Maine lobster,” Martin, who died in 2004, told the Associated Press in 2003. “The art was so striking that I knew instantly that I had found my artist!”

More importantly, Carle had found his calling. He released his first solo publication, 1, 2, 3 to the Zoo, a year later, and never looked back.

“I often joke that with a novel you start out with a 35-word idea and you build out to 35,000 words,” Carle told the Guardian. “With a children’s book you have a 35,000-word idea and you reduce it to 35. That’s an exaggeration, but that’s what’s taking place with picture books.”

An illustration from Eric Carle’s children’s book The Very Hungry Caterpillar. Courtesy of Penguin Young Readers.

Carle is survived by two children, Rolf and Cirsten Carle, and sister Christa Bareis.

Together with Barbara “Bobbie” Morrison, his second wife, Carle opened the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts, on his 64th birthday in 2002.

It is the nation’s first institution dedicated to picture-book art. A touring exhibition organized by the museum, “Eric Carle’s Picture Books: 50 Years of ‘The Very Hungry Caterpillar’,” celebrated the 50th anniversary of the author’s most famous title in 2019.