In 1966, Ernest Cole fled his native South Africa, never to return. The nation’s first Black freelance photographer, he carried with him a secret cache of images documenting the evils of apartheid—photos he knew that could never be published in the county of his birth.

Instead, he went to New York City, where Magnum Photos and Random House published his House of Bondage, exposing South Africa’s horrific apartheid system to the world. The groundbreaking book became international news, helping fuel the anti-apartheid movement.

In 1968, Cole wrote in Ebony that he wanted his photography book “to show the world what the white South African had done to the Black.”

“I knew that if an informer would learn what I was doing I would be reported and end up in jail,” he continued. “I knew that I could be killed merely for gathering that material for such a book and I knew that when I finished, I would have to leave my country in order to have the book published. And I knew that once the book was published, I could never go home again.”

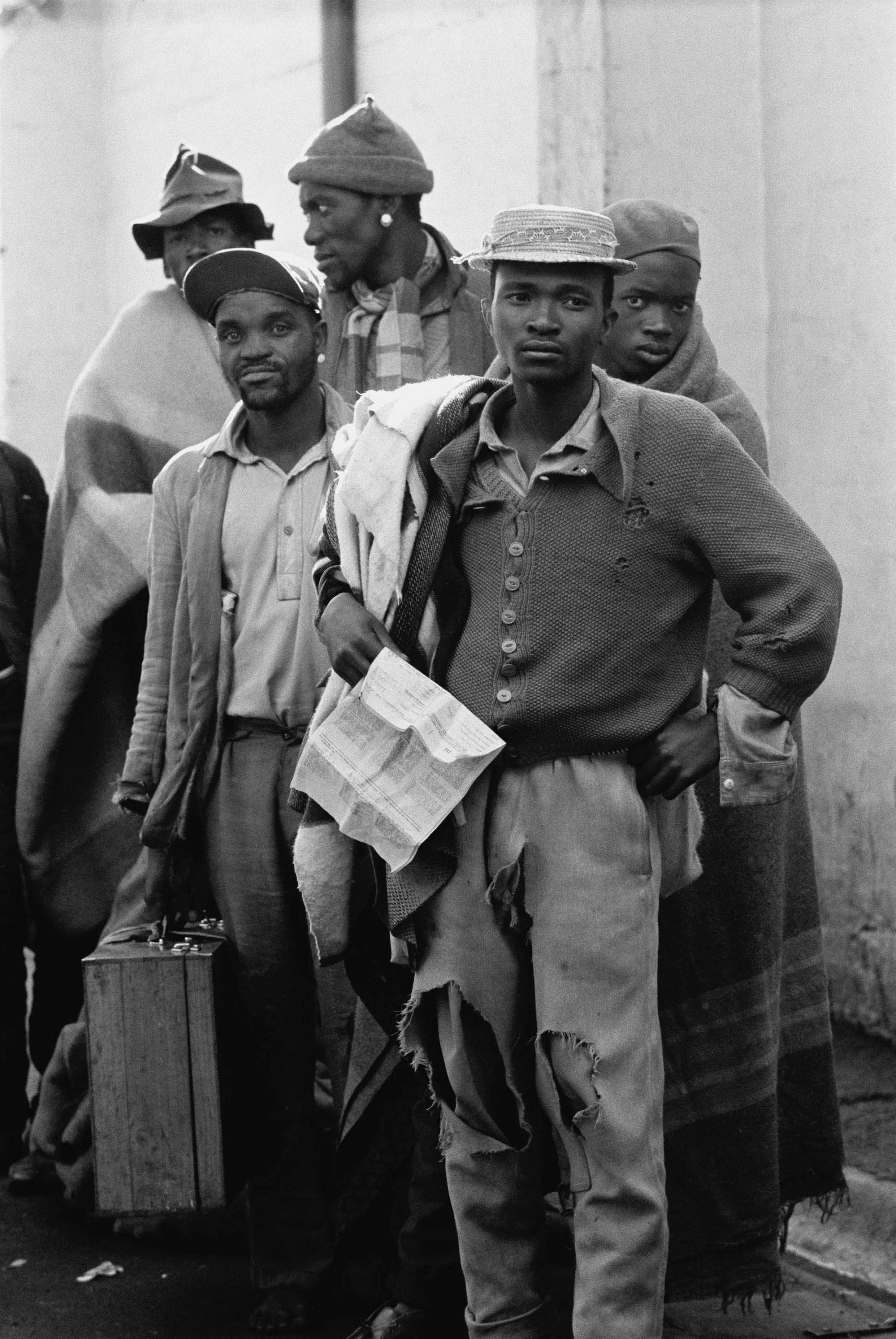

Ernest Cole, from House of Bondage. Handcuffed blacks were arrested for being in a white area illegally. Photo ©Ernest Cole, courtesy of Magnum Photos.

But Cole‘s fame was short-lived. He gave up photography in the 1970s, and died destitute, at just 49 years old, in 1990. His original negatives were believed to have been lost.

Until a few years ago, that is. In 2018, Cole’s heirs found 60,000 negatives in a Stockholm bank vault. Now, the first exhibition featuring works from Cole’s rediscovered archive is on view at at FOAM, the Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam.

“Ernest Cole: House of Bondage” showcases Cole’s pioneering work, and the obstacles he overcame in order to capture the groundbreaking images of oppression.

Born in 1940, Cole started taking photographs at just eight years old. South African authorities greatly restricted the movement of Black people, but Cole was able to change his registration to the less constrained category of “colored.” (One of the tests was whether or not a pencil would get stuck in your hair.)

This relative freedom of movement gave Cole the ability to photograph shocking scenes of South Africa life.

He went to the mines, where men lined up to be processed for grueling manual labor, living in harsh barracks far from home. He went to schools where Bantu children worked on the floor due to lack of desks. He visited Black servants working for white families, their living quarters furnished with milk crates and newspaper carpeting.

Ernest Cole, from House of Bondage. Students kneel on the floor to write. The government did not always provide schools for black children. Photo ©Ernest Cole, courtesy of Magnum Photos.

Other photos show Black men handcuffed and young boys behind bars, arrested for being caught in a white neighborhood. There are packed segregated trains, the Black passengers clinging precariously to the outside of the cars in order to travel during rush hour, and overcrowded hospitals with Black patients in desperate need of treatment.

When Cole finally published House of Bondage in 1967, the images shocked the world—as the artist knew they would. Ahead of the FOAM exhibition, Aperture reissued the book, introducing this first-person account of the everyday violence under apartheid to 21st-century audiences.

See more photos from the exhibition below.

Ernest Cole, from House of Bondage. It is against the law for black servants to live under the same roof as their employers. In a private home, servants would have a separate little room in the backyard. She lives on the edge of opulence, while her own world is bare. Newspapers are her carpet, fruit crates her chairs and table. Photo ©Ernest Cole, courtesy of Magnum Photos.

Ernest Cole, from House of Bondage. Servants are not forbidden to love. The woman holding this child said: “I love this child, though she’ll grow up to treat me just like her mother does. Now she is innocent.” Photo ©Ernest Cole, courtesy of Magnum Photos.

Ernest Cole, from House of Bondage. Acres of identical four-room houses on nameless streets. Many were hours by train from city jobs. Photo ©Ernest Cole, courtesy of Magnum Photos.

Ernest Cole, from House of Bondage. Africans throng Johannesburg station platform during late afternoon rush hour. The train accelerates with its load of clinging passengers. They ride like this through rain and cold, some for the entire journey. Photo ©Ernest Cole, courtesy of Magnum Photos.

Ernest Cole, from House of Bondage. With no room inside the train, some ride between cars. Which black train to take is a matter of guesswork. They have no destination signs and no announcement of arrivals is made. Head car may be numbered to show its route, but the number is often wrong. In confusion, passengers sometimes jump across tracks and some are killed by express trains. Whistle has sounded, train is moving, but people are still trying to get on. Photo ©Ernest Cole, courtesy of Magnum Photos.

Ernest Cole, from House of Bondage. These boys were caught trespassing in a white area. Photo ©Ernest Cole, courtesy of Magnum Photos.

“Ernest Cole: House of Bondage” is on view at FOAM, Keizersgracht 609, 1017 DS Amsterdam, Netherlands, January 26–June 14, 2023.