Every one of Es Devlin’s designs and sculptures, however ambitious and monumental, is built on the most modest of foundations: paper. With it, the British artist sketches and draws, cuts and folds, sculpts and manipulates to give form to her ideas, before they’re constructed in life-sized proportions. It’s the ideal medium, she said: “Paper is so cheap and ephemeral as a core material, which means there’s real freedom within the mark-making.”

Devlin was speaking to me at last week’s preview of “An Atlas of Es Devlin,” her first monographic museum exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt in New York. Dressed in minimalist black-and-white, she was unpacking the centrality of paper in the show, which delves into her three-decade practice by disgorging her vast archive of drawings, cardboard models, illuminated paper cuts, and other ephemera. Put together, they illustrate her creative process right down to the last design note.

For an artist best known for her kinetic sculptures, immersive installations, and massive stage designs for the likes of Beyoncé and Adele, “Atlas” is a surprisingly intimate exhibition. Or as Devlin puts it, the show has allowed her to access “radical vulnerability,” a tip she picked up from art critic Jerry Saltz’s 2020 book, How to Be an Artist.

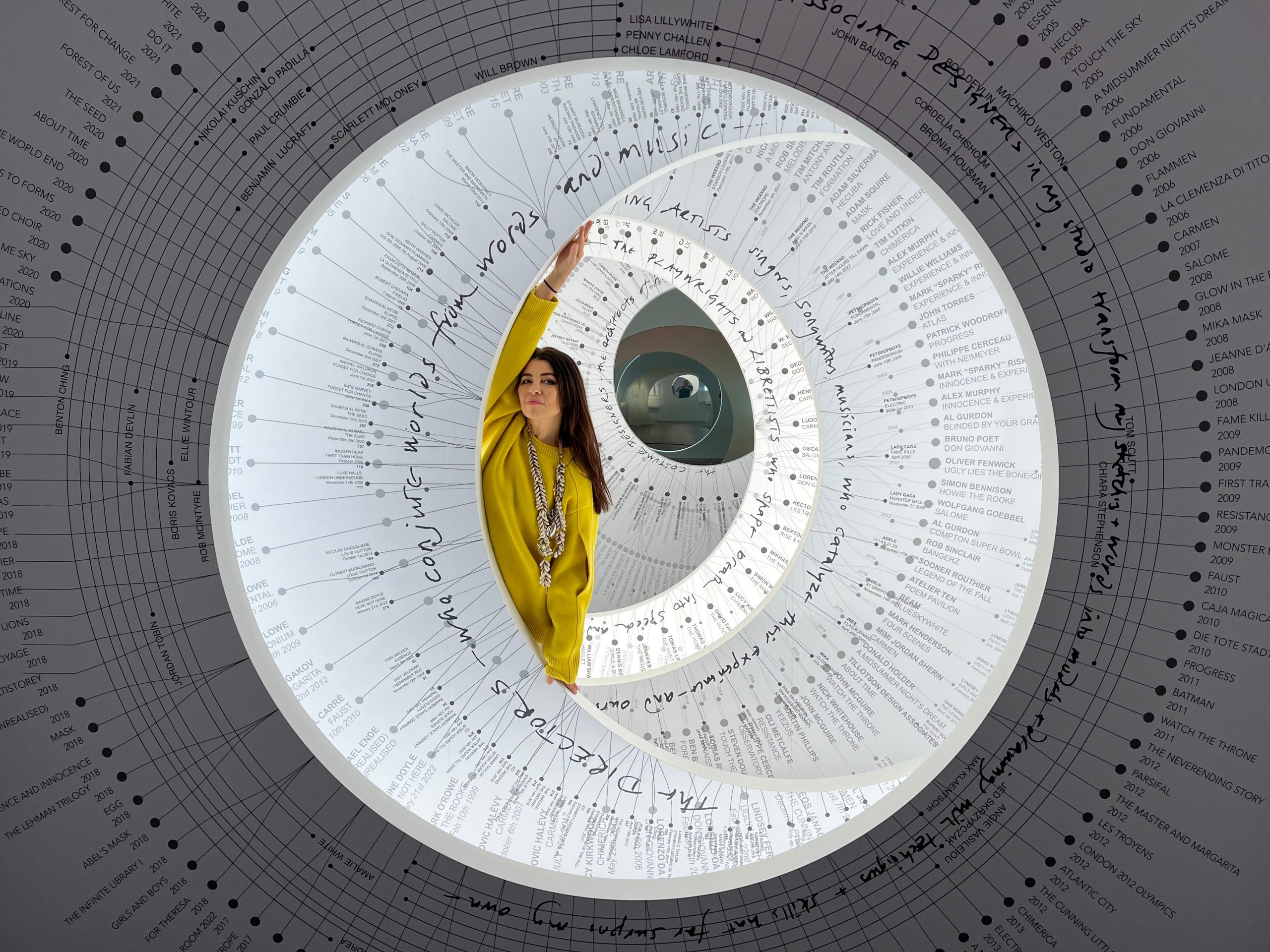

Es Devlin in her studio. Photo courtesy of Es Devlin.

“It’s very personal,” she said about the presentation. “This is literally me getting stuff out of the bin bag stuff I made along the way, not least to retrace my own steps and find my own threads, but also hopefully to help people understand that the large-scale works have quite humble roots.”

Trained in fine art and theater design at London’s Central Saint Martins, Devlin commenced her practice in the mid ’90s creating sets—each more sculpturally daring than the last—for venues such as the Bush Theatre and London Theatre. Her canvas would expand in the coming years as she signed onto projects from opera and ballet productions to fashion activations such as the immersive labyrinth she designed for Chanel. By 2012, she was taking on the closing ceremony for the London Olympics, then in 2022, the NFL Super Bowl halftime show.

Es Devlin sketches on view at “An Atlas of Es Devlin.” Photo: Elliot Goldstein © Smithsonian Institution.

But some of Devlin’s most high-profile works have been her designs for arena concerts, headlined by names from The Weeknd to Kanye West. She built a cheeky stage for Miley Cyrus’s 2014 tour centered on the pop star’s infamous tongue; she installed massive rotating, illuminated sculptures for Beyoncé’s Formation World Tour. For Adele’s 2016 concerts, Devlin built a huge screen on stage, projected with the songstress’s closed eyes, which opened once she sang the first line of the first song, “Hello.”

“It starts with the music and lyrics—I take lyrics really seriously,” Devlin explained of her approach to these large stages. “Then it goes into a broader understanding of the context: Why was the piece written? What’s the context of the work? What’s the story behind it? And then beyond that, it’s really also instinctive: what does the space need?”

Models on view at “An Atlas of Es Devlin.” Photo: Elliot Goldstein © Smithsonian Institution

However big these projects get, though, Devlin has not lost sight of what—and who—she’s building for: “We have a responsibility to the audience, whether it’s in a small play for 75 people or in a stadium for 200,000. If we’re asking them to gather, then we must hold space for them and for the performer who’s offering absolute vulnerability.”

Devlin has likewise centered the experiential in “Atlas.” Before they enter the show, visitors are ushered into a darkened room, decorated to look like a studio space with large books open at the table and sketches tacked to the walls (more paper!). There, projections mapped onto physical objects, accompanied by the artist’s voiceover, relay her creative process in detail. “Every audience,” Devlin narrates at one point, “is a temporary society.”

Installation photo of “An Atlas of Es Devlin” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Es Devlin Studio, courtesy of Es Devlin.

That principle, tinged with the utopian, has fueled Devlin’s community and participation-centric installations—her immersive mazes and model cities that encourage viewers to better engage with civilizational shifts and structures.

Memory Palace (2019), a chronological 3D landscape, aimed to chart and provoke evolutions in human thought, just as The Conference of Trees (2021), an indoor installation of 197 trees at COP 26, emphasized the environmental imperative. Her early experiment with A.I., Poem Portraits (2019), which invited users to contribute a word to a collective, algorithmically generated poem, urged humans to consider machine collaboration—on their own terms.

Memory Palace (2019) by Es Devlin, at the Pitzhanger Manor and Gallery, in Ealing, London. Photo: Dominic Lipinski/PA Images via Getty Images.

A.I. today, she said, “is beginning to be more than human intelligence.” As a “useful” way of approaching the tool, she pointed out that nature and biology, with their microbial and bacterial entities, encompass more than one intelligence. “When I look at a neural network visually and I look at a bifurcating network of rhizomatic systems,” she added, “I see the connection.”

That Devlin’s work spans mediums and achieves scale makes sense for a world-builder whose project has been to interrogate our species’ relationship with everything else in our environment. It’s a profound venture that, in her words, “invites audiences to practice ‘interbeing.'”

Installation view of “An Atlas of Es Devlin” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo: Es Devlin Studio, courtesy of Es Devlin.

At “Atlas,” we’re speaking in a gallery lined with her earliest artworks—nude studies etched in notebooks, abstract oil portraits, charcoal sketches—which she likened to “work at school art shows.” Still, for her, they contain seeds for her latter-day practice.

She pointed to a series of drawings she created of a girl trapped in various boxes, a juxtaposition of an organic form against a geometric one. In another richly painted work is depicted a tuba entwined with leaves and branches, presenting a “common harmony” between nature and manmade instruments.

“Some of the work that I’m making now is still interested in how choral music and forms of species can be seen to be continued.” she said. “The project of my practice is to explore that continuity between us and more-than-human forms, be that A.I. or every other living thing on the planet. I do think the most useful application of the craft I’ve been handed over 30 years is to explore and express that sense of continuity.”

“An Atlas of Es Devlin” is on view at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2 East 91st Street, New York, through August 11, 2024.