“One night I dreamed that I painted a large American flag, and the next morning I got up and went out and bought the materials to begin it.” That’s how American artist Jasper Johns recalled the creation of one of his most famous works, Flag, completed between 1945 and 1955.

Being both a representation of a thing and the thing in itself, Flag is as contemporary a work of art as artworks get. And yet, this 42-by-60 inch twist on the star-spangled banner—currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City—used a technique that is as old as the murals and mosaics of ancient Greece: encaustic painting.

Simply put, encaustic painting is a type of painting where artists paint not with pigment, but pigment infused with hot wax that can be applied to a surface to create a layered, textured, and semi-transparent effect. Taken from the Greek word enkaustikos, meaning “to heat” or “burn in,” encaustic painting first emerged in the 4th-century B.C.E. Initially used to waterproof ships, artists soon discovered that, when combined with pigments, the wax could be used for decorative purposes, too.

Detail of an encaustic Fayum portrait (1st-2nd century). Photo: DeAgostini / Getty Images.

Despite being slower, more laborious, and often more expensive than tempera painting (another popular painting technique of classical antiquity that used fast-drying pigment mixed with egg yolk binder), encaustic painting was used often and applied to a variety of canvases, from the bows of ships to the cartonnage canvases of priceless Fayum portraits. Encaustic also proved more durable than tempera, capable of withstanding temperatures of over 150 degrees Fahrenheit, which partially explains why the aforementioned portraits, made between 200 and 400 C.E., were so incredibly well-preserved.

Though dwindling in popularity from the early Middle Ages onward, encaustic painting made a comeback during the 20th century—not only because modern artists disheartened by the industrial revolution gained a renewed appreciation for ancient crafts, but also because the many inventions of this revolution, notably portable electric heating devices, made encaustic painting faster and easier than ever before.

Jasper Johns, Flag, at Sotheby’s in London, 2014. Photo: Carl Court/Getty Images.

This brings us back to Jasper Johns and Flag, which isn’t a painting so much as it is a collage, constructed from strips of cloth and newspaper clippings fastened to a piece of bedsheet. Like ancient artists before him, Johns not only used wax as an adhesive, but also as pigment.

The quick-drying method also allowed individual brush strokes to stand out, enabling him to create layers and textures—a technique he would return to time and again over the course of his career, in paintings from Target (1961) to Near the Lagoon (2002–03)

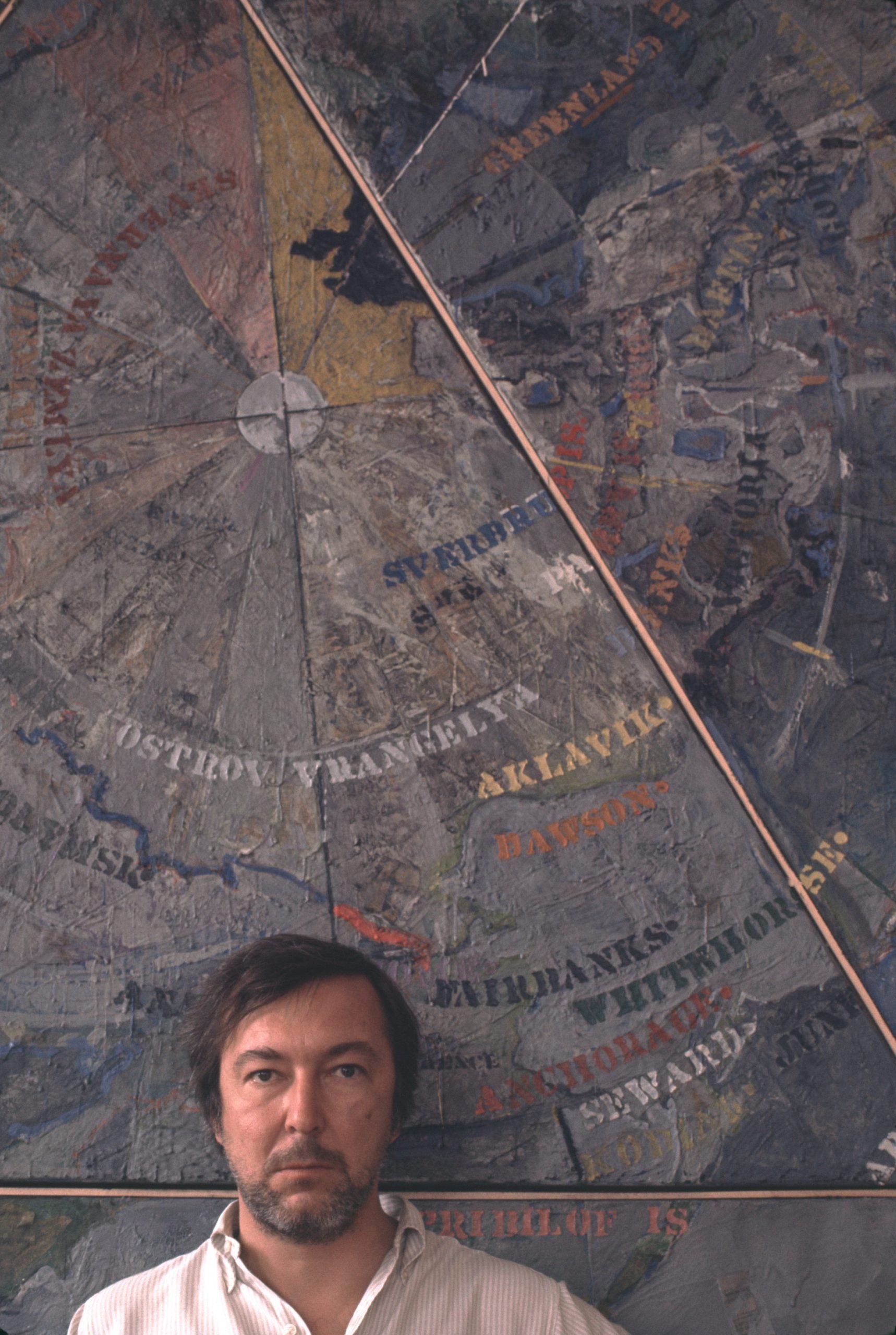

Artist Jasper Johns photographed at an exhibition of his work at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1977. Photo by Jack Mitchell/Getty Images.

A closer look at Flag reveals that Johns’s use of encaustic was far from trivial. At first sight, the artwork appears to be little more than a pompous, hollow display of American patriotism and maybe, to an ironic extent, that was the point. Beyond that, however, the wax allows viewers to see the carefully selected newspaper clippings underneath the red, white, and blue—clippings that indicate the lengthy history behind the flag informing the numerous and often contradictory meanings this object has acquired since the birth of the country it represents.

What inspired Mary Cassatt’s portraits of mothers? Why did Jackson Pollock paint on the floor? Eureka investigates the origins of artists’ most famous works and techniques, unpacking how great art ideas happen.