John Frederick William Herschel was a man of many talents. Born in England during the late 18th century, he was an accomplished mathematician, chemist, and inventor. He created the Julian Day system, which helps astronomers keep track of cosmic time, and named four of the 27 moons of Uranus, a planet that had been discovered by his father, who was a polymath in his own right.

Interested in light, color, and color blindness, Herschel spent years experimenting with photograms. Also known as sun prints, this early form of photography involved coating paper with chemicals sensitive to ultraviolet light to capture an image. His eureka moment came in 1842, when he learned that a combination of iron salt solutions, ferric ammonium citrate, and potassium ferricyanide yielded a particularly crisp pictures, colored in deep blue, at low costs.

John Frederick William Herschel, photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron. Photo: The Royal Photographic Society Collection / Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Getty Images.

These pictures, later referred to as cyanotypes—from the Greek words kyáneos or “dark blue” and “týpos” or mark—could be put to a variety of uses. In addition to taking cyanotypes of people and places, Herschel also made copies of his notes and diagrams.

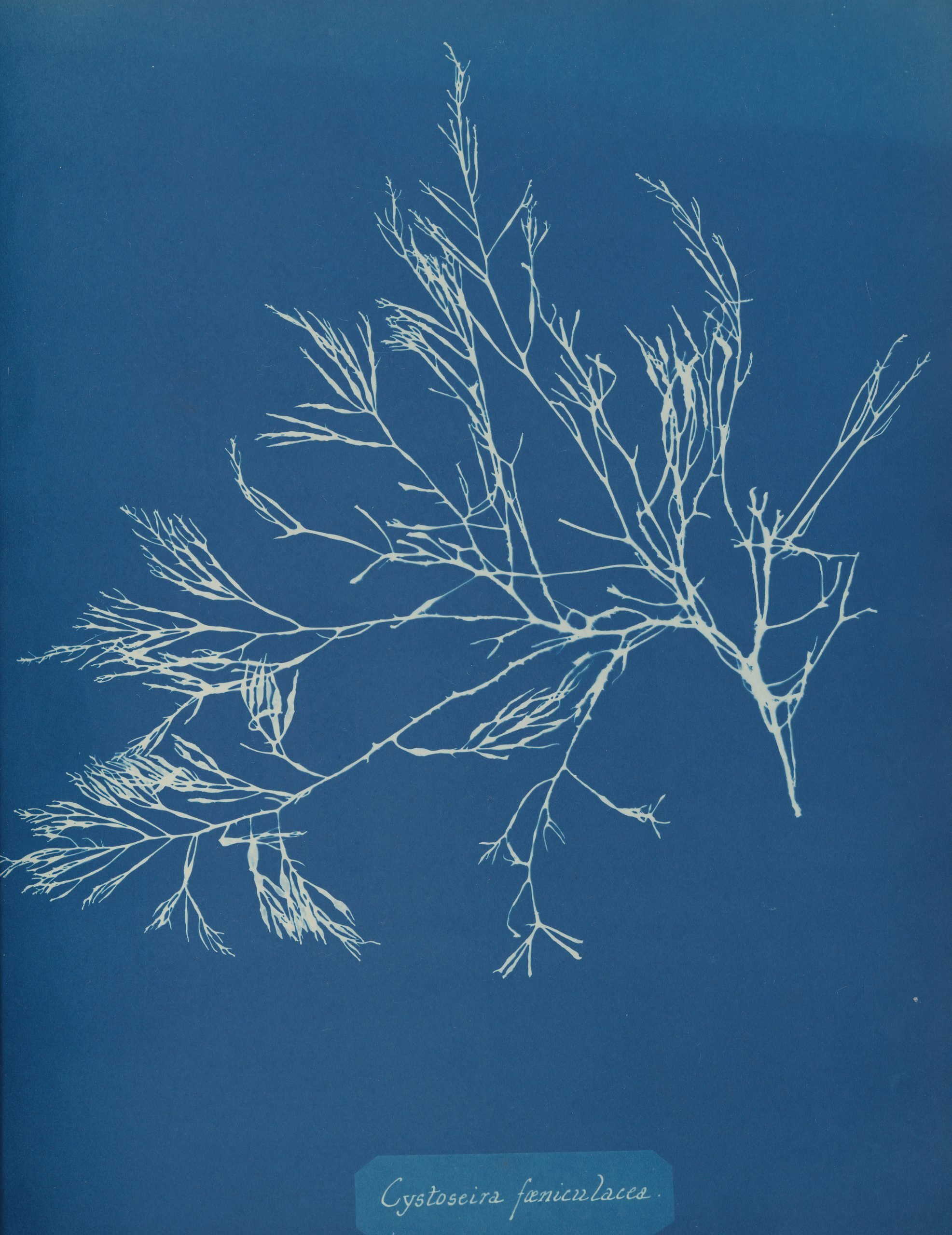

Some of the most famous and influential cyanotypes were made by Anna Atkins, an English botanist who leveraged the technique to publish what is widely regarded as the first photographic illustrated book, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, which appeared in 1843. Prior to Herschel’s invention, botanists called on artists to create detailed drawings, etchings, and engravings of plants to accompany their writing. Atkins, though a competent illustrator in her own right, turned to cyanotypes because they could produce images more quickly and more accurately than any human hand.

Title page of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions by Anna Atkins. Photo: Science & Society Picture Library/SSPL/Getty Images.

During the 19th century, cyanotypes became a recurring feature in botanical and other scientific texts. “With the introduction of photography, you get a whole new opening up of how natural history and science can be represented in print,” Andrea Hart, library special collections manager at the Natural History Museum in London, noted in an article on Atkins’s work.

Despite the technique’s growing presence in academic publishing, it wasn’t until the 1880s—when continued tinkering with cyanotypes brought people to a point where all they needed was a bit of water to fix their images so that the chemicals no longer reacted to sunlight exposure—that the process became truly mainstream.

Cyanotype of a family standing in front of a dispensary on St Paul Island, Alaska, 1886. Photo: Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images.

Initially used for commercial photography, cyanotypes have since developed into a popular medium for artists and fine art photographers. For her famous “Still Life” series, Iranian photographer Gohar Dashti destroyed organic materials like leaves and filaments so that the chaotic, decaying cyanotypes were not just visually interesting, but also reflective of her traumatic experience growing up under the iron fist of Iran’s religious dictatorship.

Also worth noting is British artist Joy Gregory’s 2020 photography series “Invisible Life Force of Plants,” comprised of cyanotype and lumen prints of plants. Connected by a common theme of “economic botany,” the use of plants and natural resources for human survival, these prints offer an homage to Atkins’ Photographs of British Algae, bringing the story of cyanotypes full circle.

What inspired Mary Cassatt’s portraits of mothers? Why did Jackson Pollock paint on the floor? Eureka investigates the origins of artists’ most famous works and techniques, unpacking how great art ideas happen.