The abrupt cancellation on Tuesday of the installation-cum–performance work Exhibit B: Third World Bunfight at the Barbican Centre in London, following angry protests outside the building, means that London audiences won’t get to judge for themselves whether the work by white South African theater director Brett Bailey is a vile piece of racist condescension, or, instead, a challenging reflection on the history of Western colonialism, the barbarity of slavery, and the plight of contemporary black migrants and refugees.

The work is part of Bailey’s “human installation” series tracing racism as evidenced in ethnographic displays. Third World Bunfight describes Exhibit B as a “look at the atrocities committed by colonial forces in German South West Africa and in the Belgian and French Congos, the plight of African immigrants living in—and deported from—Europe.”

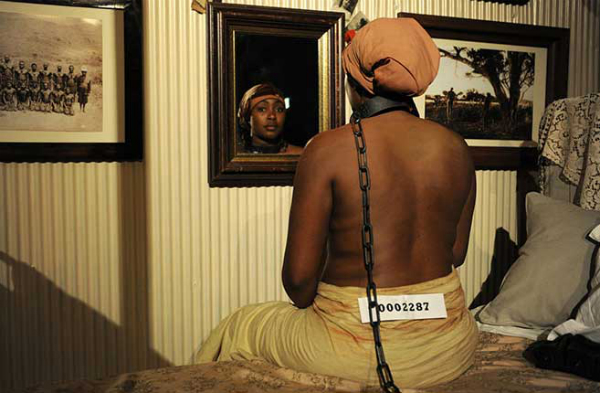

For the critics and the public who didn’t catch Exhibit B at the Edinburgh International Festival, or in the 12 other cities where it’s been presented, we will never know what we might have thought, or felt, about this sequence of tableaux vivants, which, played silently by living black actors, reworks the once common slavery-era European entertainment of the “human zoo,” according to Bailey.

In the absence of the work itself, then, what should we make of the angry accusations of racism which drove the protests that eventually shut down Exhibit B?

For this critic, the controversy reveals, more than anything, how divisive and backward looking the politics of identity have become today. For the 23,000 signatories to the petition calling for the work to be cancelled, “the likes of Bailey and his apologists need to think about how it would feel if they had their ancestors and relatives caged in the name of art.”

In other words, the petitioners (“we as Black African people”) see the work as a continued slight on those who they see as their “ancestors”—that is, a contemporary assault on what they see as their “identity,” something which isn’t something that one shapes in the here-and-now, but which is determined by one’s “ancestral” and eventually genetic roots.

Obviously, black British people can trace their origins more directly to Africa than can white British people. But this doesn’t mean that this automatically gives black British people authority over cultural explorations of the history of slavery, colonialism, and, yes, white people’s historic violence against black people.

What irked many of the protestors was the suspicion that the staging of this “human zoo” was not a critical act of reflection by a (white) artist about the history of white people’s oppression of black people, but was itself an act of objectification and subjugation—that whether its defenders admit or not, the work is implicitly racist and actually reaffirms the objectification of black people for the titillation of white gallery-goers. This is why even statements by the actors themselves, confirming that they did not think of themselves as complicit in a racist artwork, or that Bailey might harbor racist intentions, were dismissed by the protestors. The suspicion that white people and institutions are still out to oppress black people was enough for the protestors to see the work as a patronizing act of provocation and condescension, regardless of any amount of assertion to the contrary.

Without strapping him into a lie detector machine or a brain scanner, it’s impossible to know whether Bailey is, in some weird, secret way, a racist, or that all his actors might be brainwashed dupes. What we do know is that Bailey wants the work to make us feel “uncomfortable,” and while I might disagree with the protestors’ paranoid suspicions about an artist’s “real” motives, it’s also worth examining what exactly Bailey hopes to achieve by staging such a stark confrontation between an audience and an artwork.

Drawing on the tradition of much avant-garde performance art, Exhibit B exploits the discomfort that occurs when the line between fiction and reality, between the actor’s body and the real body, is dissolved. In many ways, Exhibit B repeats the rampant fashion for “authenticity” now current in theater and art—whether the trend for plays using verbatim documentary dialogue, or the fascination with artists whose mere presence in the gallery is presented as some sort of transcendent act of unmediated “communion” with the audience (think of Marina Abramović’s wild success in this respect). Being able to step back as an audience, to experience an artwork as something to consider and reflect upon as a community, is exactly what Exhibit B wants to deny us. Rather, it seems intent, like much “political” artwork and theater today, to subjugate and dominate its audience with the intent of forcing us to feel a certain way about a particular subject. And it does so as if our feeling badly will make us become better people—a bit like undergoing a particularly harsh kind of art therapy.

But here’s the thing: Do we (whatever our ethnicity) really need artists to tell us, through confrontation and manipulation, that, Hey, slavery and colonialism were really bad things? Don’t artists think that society might have figured that out by now? In which case, why the obsession with endlessly repeating the point? Are we seriously in danger of forgetting that slavery and racial oppression were the symptoms of a barbaric past, which, thankfully, we’ve turned our backs on? And are we seriously equating the divisions that exist in our own present as anything resembling those of the past?

One can only conclude that today, subjecting oneself to the repeated expression that “slavery and racism were bad” has become a sort of cultural ritual of atonement, through which we demonstrate that we’re not racists, that these are not our values. If nothing else, this doesn’t make for very interesting or complex art, since we already know what we’re supposed to think (and feel) at the outset.

And yet, while Brett Bailey’s Exhibit B might be a terrible work of art, forcing it out of the public eye stops us from deciding for ourselves. Even if this means some of us are offended, art needs to be seen to be criticized.

JJ Charlesworth is a freelance critic and associate editor at ArtReview magazine. Follow @jjcharlesworth on Twitter.