The following is from an excerpt from Hal Foster’s book of essays What Comes After Farce?, published this month by Verso Books.

The Surrealists imagined that everyone who dreams is a poet, and Joseph Beuys believed that everyone who creates is an artist. So much for the utopian days of aesthetic egalitarianism; maybe the best we can say today is that everyone who compiles is a curator. Certainly, that includes a multitude of us: we curate news feeds, song lists, and restaurant choices, among many other things, and countless websites and applications do the same for us. In fact, “curating” is so rampant that it is a regular item on annual lists of worst words; already in 2014, it was put on probation along with “skill set” and “takeaway.” Like these other terms, curating promises a new kind of agency, but it might only deliver a heightened level of administration: if people can be reduced to skill sets and arguments to takeaways, then cultural interests can be packaged as curated consumption. Often, this packaging is automatic; the algorithms know what we want before we do. Such curating suits the postindustrial aspects of an economy in which the appointed task for many people is to consume. After all, when we curate songs or restaurants, or Spotify or Eater does so for us, what do we actually produce? We cognitive laborers manipulate information, which is to say we curate the given, and this compiling often involves a great deal of complying. How many of us consider what is signed over when we click “I agree”?

Although many curators carry forward a degree of civic responsibility and altruistic concern, we have come a long way from the original avatars of curating (the root of which is cura or care): the curatores, the civil servants who oversaw public works like the aqueducts in ancient Rome, and the curati, the priests who attended to private matters of the soul in the medieval period. Any potted history of curating would also include the assemblers of courtly Wunderkammers (the cabinets of curiosities that were more natural history than art history), the keepers of royal collections of art, the décorateurs of paintings in the French Salons of the eighteenth century, the organizers of museums like the Louvre (once royal collections were nationalized), and the connoisseurs of classical sculpture and Renaissance painting from Johann Winckelmann to Bernard Berenson. Several of the scholars who founded the modern discipline of art history were also important curators. (In the late 19th century Alois Riegl oversaw the textile collections at the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna.)

The 2018 reopening of the Winckelmann Museum in Stendal, dedicated to the life and work of the scholar and archaeologist Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Photo by Klaus-Dietmar Gabbert/picture alliance via Getty Images.

Closer to our time, however, a divide developed between the university and the museum, as some academics were drawn to critical theory while most curators remained committed to connoisseurship. This divide was less marked in premodern fields of study (the Renaissance expert Michael Baxandall was much admired in both worlds), and some prominent curators in the modern area are also respected in the academy. (The Museum of Modern Art [MoMA] in New York has had a good number of these switch-hitters). Today the more relevant split is the more recent one between modern and contemporary fields (the latter has no exact date of origin—1968, 1980, 1989?), which is a schism less between the university and the museum than between scholarly curators and flashy exhibition-makers. This split was opened up when the 20th-century art museum was penetrated by the culture industry, and it was deepened when the contemporary art world expanded into the global business of art biennials and fairs. With the first development came a demand for on-site entertainment, and with the second a need for far-flung attractions. Although this is a reductive retrospect, there was a marked turn to spectacular displays at this time.

In Ways of Curating (2014) the Swiss curator Hans Ulrich Obrist evidences this split between curator and impresario. Obrist picks out unexpected precursors, such as Henry Cole, the producer of the Crystal Palace that housed the international trade fair in London in 1851, and Sergei Diaghilev, the animator of the Ballets Russes in its glory days of the 1910s and 1920s. Cole assembled his famous iron-and-glass structure in Hyde Park, not far from the Serpentine Galleries where Obrist has staged many of his own shows, and Obrist sees Diaghilev as a pioneer of the “modern form of Gesamtkunstwerk” that he has sought to develop. At the same time, Obrist pays homage to past curators who were not primarily showmen. Among others he names the German Alexander Dorner, who directed the Hannover Museum from 1925 until he was ousted by the Nazis in 1937, commissioning modernists like the Constructivist El Lissitzky to design radical exhibition prototypes; the Dutchman Willem Sandberg, a member of the Resistance who, as curator and director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam from 1938 to 1962, championed avant-garde groups such as Cobra; and the American Walter Hopps, who, along with organizing the landmark Duchamp retrospective in Pasadena in 1963, advanced the work of Robert Rauschenberg, Ed Kienholz, and others. However, Obrist reserves his highest praise for his immediate godfathers: the Swede Pontus Hultén, who, as head of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, arranged the first Warhol retrospective in 1968 (Hultén became the founding director of both the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles); the Swiss Harald Szeeman, who put Conceptual and Post-Minimalist practices on the map with his legendary exhibition “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form in Bern and London in 1969”; and the German Kasper König, who pioneered the display of site-sensitive sculpture with his decadal show Skulptur Projekte Münster. That Obrist singles out these three is telling, for they were all concerned to expand the conventional exhibition by means of capacious themes. At the same time, they can be seen as transitional figures between the old school of modernist curators and the new breed of contemporary exhibition-makers. Szeemann actually preferred the label Ausstellungsmacher, and Obrist rightly calls König “a cultural impresario.”

Marjan Pejoski’s Swan Dress in “Björk” at MoMA

Photo by Ben Davis.

In our time, this line of exhibition-makers has itself split in two. With an unlikely mix of criticality and charisma, serious curators like Okwui Enwezor, the late director of the Haus der Kunst in Munich, and Lynne Cooke, a senior curator at the National Gallery in Washington, have produced ambitious theme shows à la Hultén, Szeemann, and König. But a problem in this approach emerged already in the 1990s: as some artists began to act as curators, exhibiting objects that museums had kept from view (a key instance was Mining the Museum [1992–93] by Fred Wilson), some curators started to behave like artists, juxtaposing artworks as so much material to manipulate. Obrist says, somewhat disingenuously, that he shies away from this tendency (“I’ve never thought of the curator as a creative rival of the artist”). At the same time, pace his critics, Obrist does not quite fit the category of flashy exhibition-maker either. The standout here is Klaus Biesenbach, director of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, who, as chief curator at large at MoMA, arranged overblown retrospectives of crossover stars such as Marina Abramović and Björk. Life-styling of this sort is depressing: such curating has little relation to scholarship, let alone criticism, and little sense of public service that still guides some curators in Europe and elsewhere. At the beginning of the practice known as institution critique, Robert Smithson insisted that the artist must understand the art apparatus that she is “threaded through” in order to challenge its usual operation. Today many artists are only too happy to be so threaded and many curators only too eager to do the threading. Hultén, Szeemann, and König came up against a rigid system that they worked to free up. Too often the recent breed of exhibition-makers is content not only to inhabit that loosened system but also to be the agents of its exploitation by fashion, music, and entertainment industries.

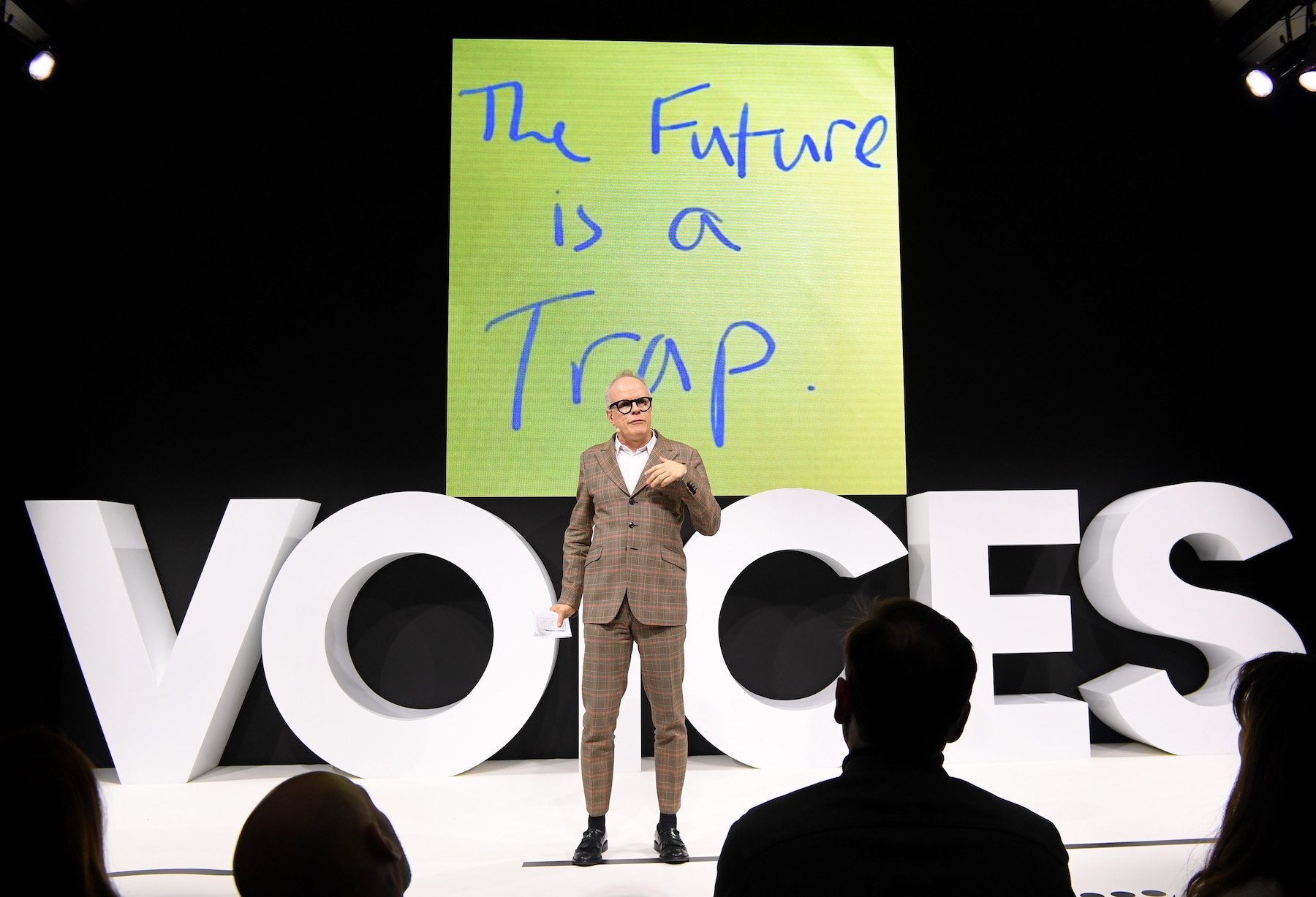

Obrist has not taken undue advantage of his celebrity, and his commitment to his artists is earnest, almost devout; he describes his youthful pilgrimages to Peter Fischli and David Weiss, Christian Boltanski, and Gerhard Richter as conversion experiences. And his energy has not flagged over the years: a 2014 profile in the New Yorker logged him at roughly 2,000 trips, 2,400 hours of taped conversations, and 200 catalogues over the prior twenty years. (Like many artists, he has assistants, but these numbers are still extraordinary.) To this day, most of his life is spent on the road, contacting collaborators and conceiving exhibitions as if there were no tomorrow, and indeed the present is foremost in his sights. Obrist reports a millennial epiphany during a January 2000 conversation with Matthew Barney about “a new hunger amongst artists for live experience,” and like his curatorial colleagues in relational aesthetics, Nicolas Bourriaud, former head of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and Daniel Birnbaum, current director of the Moderna Museet, he is most devoted to time-based art, especially performances and installations staged by artists of his generation such as Rirkrit Tiravanija, Pierre Huyghe, Philippe Parreno, and Dominique Gonzales-Foerster. For Obrist, curation involves “infinite conversation” as well as extensive collaboration. In 2006, with another mentor, Rem Koolhaas, he launched “The Serpentine Marathon,” a “24-hour polyphonic knowledge festival where all kinds of disciplines meet,” and he has adapted this strategy of accumulation to other forms, too, such as the manifesto. This is not for everyone (if hell was other people for Sartre, it is nonstop art talk for me), and certainly not enough attention is given to the quality of the discourse involved or of the community effected. For Obrist, the doing is all.

Interview marathon at the Serpentine Galleries, London. Image courtesy Serpentine Galleries.

There were three preconditions for the recent shift in exhibition-making, all of which should be grasped dialectically. (They also line up, roughly, with the proposed start dates of “the contemporary” noted above.) The first crux was Conceptual art of the 1960s, especially as it prompted the poststudio and postmedium practices of the 1970s and 1980s. As Obrist comments, Conceptualism challenged “the idea of art as the production of material objects,” permitting almost anything—a statement, a snapshot, the slightest gesture—to qualify. Obviously, this opened up the field of art, as is evident in the interdisciplinary terms that Obrist cites as essential to contemporary production, such as the Gesamtkunstwerk, the collection, the library, and the archive. (He thinks in terms less of specific histories of genres, mediums, and exhibitions than of one big “history of the format.”) At the same time, this interdisciplinarity often came at the cost of disciplinary rigor, and the expansion of art also meant an extension of its academic administration. (Curatorial studies programs are now plentiful, and they are often placed alongside MFA programs.) Moreover, what art could better match an economy of cognitive labor than one given over to immaterial knowledge? So, too, Obrist champions “the creative self,” which is the very term used by Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello in their analysis of “the new spirit of capitalism.” And the Obristian motto “Don’t Stop” perfectly suits a digital work regime that has become 24/7.

Second, the shift in exhibition-making with Hultén, Szeemann, and König has had ambiguous consequences, which might be evoked through a statement made by Jean-François Lyotard on the occasion of his 1985 show “Les Immatériaux” at the Centre Pompidou (which Obrist regards as another landmark): “The exhibition is a postmodern dramaturgy.” On the one hand, this dramaturgy suggests how the thematic show, taken up by philosophers like Lyotard (not to mention Jacques Derrida and Bruno Latour), can stage key questions of our time, as “Les Immatériaux” did in relation to his theses about the end of modern master narratives and the rise of postmodern knowledge protocols. On the other hand, this staging can easily slip from inquiry into showmanship. There is a further twist with Obrist, who may be more networker than impresario, for, if we are to believe Boltanski and Chiapello, networking is more important to the new spirit of capitalism than spectacle is. In a sense, Obrist is a human aggregator, almost a social media platform or a hive mind of one. This is implicit not only in his hectic meeting-and-greeting but also in his semi-anonymous prose, which sometimes suggests the language of a collective Wiki-brain. Although Ways of Curating is a kind of Bildungsroman, it does not display much personality. Obrist is like Warhol in this regard, a cipher who is at once iconic and spectral. (They also share a compulsion to record.)

What Comes After Farce? by Hal Foster (Verso Books, May 2020).

Third, as one might expect, 1989 is a hinge moment for this generation of curators. Born in 1968, Obrist pinned his hopes on the transformative years when he came of age, and, in many ways, he is a product of the cultural interchange facilitated by “the new Europe” (as it was optimistically called in the 1990s) permitted by the breakup of the Soviet bloc. Inspired by the Martinican writer Édouard Glissant, Obrist is also taken by notions of “artistic creolization” and “archipelic thought,” and yet what Glissant and Obrist see as a new “mondialité” that allows for cultural differences, others might regard as a globalization that homogenizes such differences brutally. (It is both, and that is what must be thought.) At times, Obrist is too affirmative about our neoliberal age—indeed, he is its creature—but then it would be difficult to move as fast as he does if he were not powered by positive thinking.

What about all those shows, conversations, and books, with the prospect of many more to come? Obrist is not alone in this respect, and it prompts the question for what present, let alone what future, are such archives complied. What audience, now or later, will be able to process it all? (Could it be that all this curating needs … a curator?) Obrist presents his project, especially the conversation marathons, as a “protest against forgetting” (a phrase borrowed from the late historian Eric Hobsbawm, one of his many interviewees). At the same time, his avant-gardism also commits him to ceaseless change. One of his “guiding principles” is that an exhibition “should always invent a new rule of the game” or at least “a new display feature.” (The last lines in his credo concern how “digital curating” will develop “new formats” for “our future.”) All this flying around, inventing rules, and reformatting might be a protest against forgetting; it might also be a fast track to oblivion.