A project funded in part by Brooklyn’s Eyebeam Art and Technology Center has won a Pulitzer Prize in international reporting.

“Built to Last,” a four-part investigative series on long-term incarceration and detention of the Uighur people, a Muslim minority, in the Xinjiang region of China, was published by Buzzfeed in 2020. It is a collaboration between reporter Megha Rajagopalan, architect Alison Killing, and Christo Buschek, a programmer and digital security trainer.

Together, the trio used sophisticated satellite technology to identify how the Chinese government was censoring images of detention camps and where the camps were located.

Funded by Craig Newmark Philanthropies, the eponymous foundation from the Craigslist founder, Eyebeam Center for the Future of Journalism, founded in 2018. offers commissions of $500 to $5,000 to help artists tell news stories in innovative ways. (The article series was also supported by Open Technology Fund and the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting.)

“We want as much as possible to remain flexible to news cycles and be a source not just for larger, long-term projects, but also breaking ones that require immediate funding,” Marisa Mazria Katz, the editorial director of the program, told Artnet News. “I knew immediately the impact a piece like this could have.”

Killing, the head of architecture and urban planning firm Killing Architects, met Rajagopalan, a Buzzfeed staffer, at a workshop in 2018. They immediately began discussing ways to investigate Chinese detention camps even though journalistic access to the country is extremely limited.

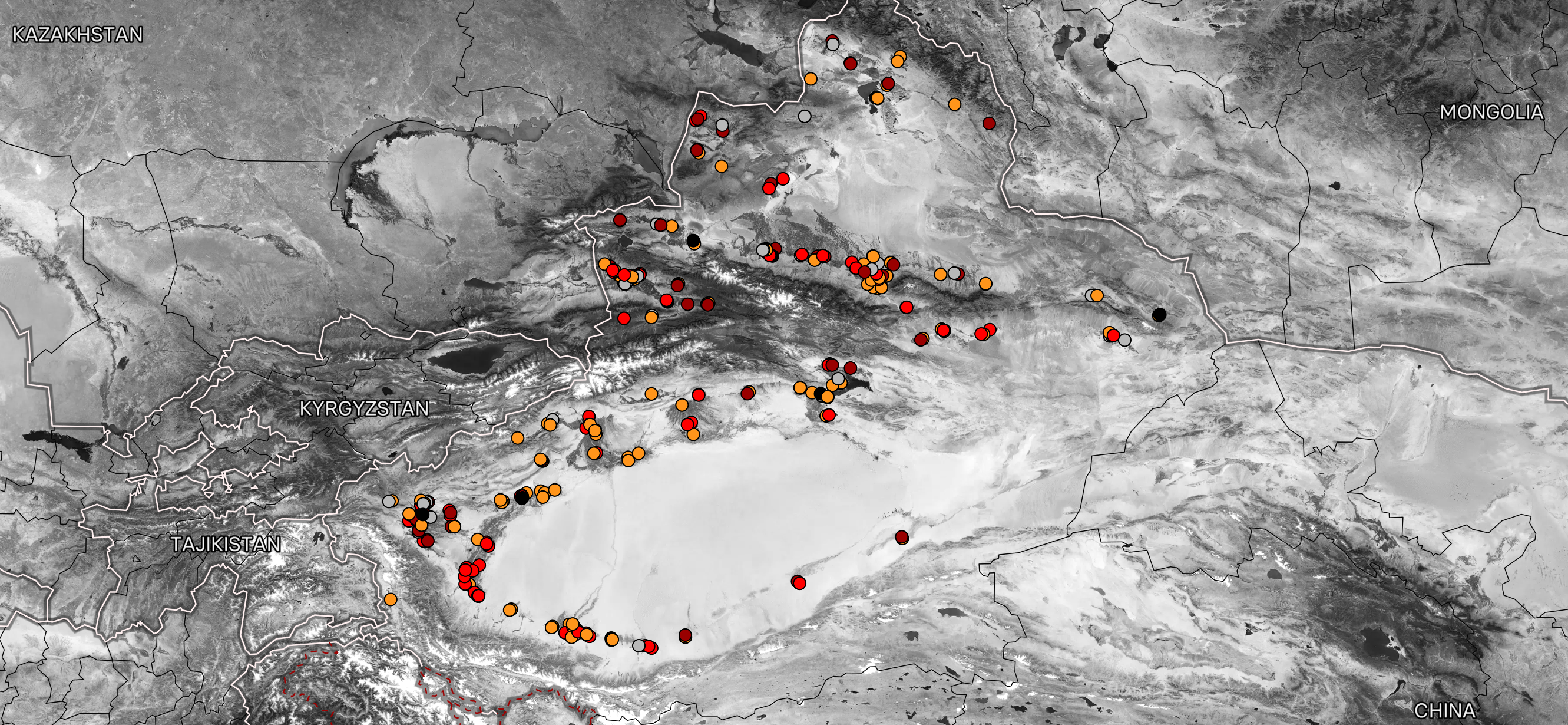

Satellite imagery of Chinese prisons and internment camps. Image courtesy of Alison Killing.

“At the time, it was believed there were one million people detained [in China] and that there were 1,200 camps in existence, but only a few dozen had been found,” Killing told Artnet News. “We realized that satellite imagery might be a good way to investigate the camps and that we had complementary skills to do this work, so decided to join forces.”

Buschek was brought on for added expertise when the two realized that Baidu Maps, which offers maps and satellite imagery of mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan, was censoring the locations of known camps.

The trio identified 50,000 areas where satellite imagery was being obscured and compared those areas to other imagery from Google Earth, Planet Labs, and the European Space Agency’s Sentinal Hub Playground.

“The satellite imagery research was used to locate likely camp locations and then to verify those,” Killing said. “There were key features that we could see in the imagery that suggested a given compound was likely to be a camp, including guard towers, heavy perimeter walls, barbed wire fencing in courtyards. We corroborated these locations via ground level imagery, media reports, and government tender documents.”

Altogether, they found 428 prison compounds—many of which have been built or expanded since 2016, the start of the government’s latest crackdown on Turkic minority culture. The camps are also used as a source of unpaid laborers for Xinjiang factories, according to the project’s findings, which were corroborated with 28 interviews with former detainees.

The Pulitzer win is the first for Buzzfeed. The committee praised the investigation as “a series of clear and compelling stories that use satellite imagery and architectural expertise, as well as interviews with two dozen former prisoners, to identify a vast new infrastructure built by the Chinese government for the mass detention of Muslims.”

The investigative effort was an international one, with Killing based in the Netherlands, Rajagopalan in London, and Buschek in Berlin.

“What happens in Xinjiang is a tragedy of epic proportions. Living in Europe, people often think that such grave violations of human rights and genocide are a thing of the past,” Buschek told Poynter. “I hope people understand that such acts are still happening today and can happen anywhere.”

The trio is hopeful that their investigative efforts will help lead to reform.

“We’ve been told,” Killing said, “[that] our work has helped inform the work of U.S. Congress and the bill on forced labor which is currently making its way through the U.S. Senate.”