Author Brigitte Benkemoun’s husband bought a vintage Hermès address book on eBay. When it arrived, Benkemoun discovered it contained notes dated from 1951 and pages of contact information for such artistic legends as Balthus, Brassaï, Andre Breton, Jean Cocteau, Paul Eluard, Leonor Fini, and others. Eventually, through some sleuthing, Benkemoun discovered the book had belonged to none other than the artist and muse to Picasso, Dora Maar and she set out on her own journey to discover more about Maar’s illustrious life.

Achille de Ménerbes

22 rue Petite Fusterie

Avignon

A-B: The first entry is illegible because it is partly blotted out with black ink. The second might be ANDRADE, then AYALA. On the fourth line is the first familiar name: ARAGON! Followed by a few contacts that call up nothing for me: ACHILLE de MÉNERBES, BERNIER, BAGLUM . . . Then a few entries for whom he or she listed an address as well, perhaps because they were closer friends: BRETON, 44, rue Fontaine; BRASSAÏ, 81, rue Saint-Jacques; BALTHUS, château de Chassy, Blismes, Nièvre.

For the letter C, COCTEAU is the first entry: 36, rue de Montpensier, RIC 5572, or 28 in Milly. But are the first entries always the closest friends? And this poet was such a figure on the Paris social scene that everyone must have known his number. Followed by the painters COUTAUD, 26, rue des Plantes; CHAGALL, 22, place Dauphine . . .

The gaze behaves like a paparazzo, snubbing the lesser-knowns to focus only on the VIPs: ÉLUARD, GIACOMETTI, Leonor FINI, NOAILLES, PONGE, POULENC, Nicolas de STAËL . . . But most of the names in the address book were easy to identify on the internet: Lise DEHARME, novelist and muse for the Surrealists; Luis FERNÁNDEZ, painter and friend of Picasso; Douglas COOPER, major art collector and historian; Roland PENROSE, English Surrealist; Susana SOCA, Uruguayan poet . . .

This list was beginning to look like a postwar who’s who, a roster of special guests posted outside a reception, an index of names cited in a biography of a famous artist. It also made me think of a group photograph as it was being developed in the darkroom, each figure emerging from the red depths one by one.

Implicitly, the address book’s ownership was being revealed through these relationships. This was someone who kept company with the greatest poets of the time, many of them, though not exclusively, Surrealists: ÉLUARD, ARAGON, COCTEAU, PONGE, André du BOUCHET, Georges HUGNET, Pierre Jean JOUVE. Someone who moved even more frequently among painters: CHAGALL, BALTHUS, BRAQUE, Óscar DOMÍNGUEZ, Jean HÉLION, Valentine HUGO. Many Surrealists, some gallery owners, a canvas restorer. This was probably a painter’s address book! And since it included LACAN’s telephone number, this painter must have stretched out on his couch.

A tormented, depressive, “hysterical,” or melancholic painter. But not a bohemian, not a cursed poet: he or she kept both feet on the ground and recorded contact information for a plumber, marble mason, private hospital, veterinarian, and hairdresser. I was certain the address book belonged to a woman.

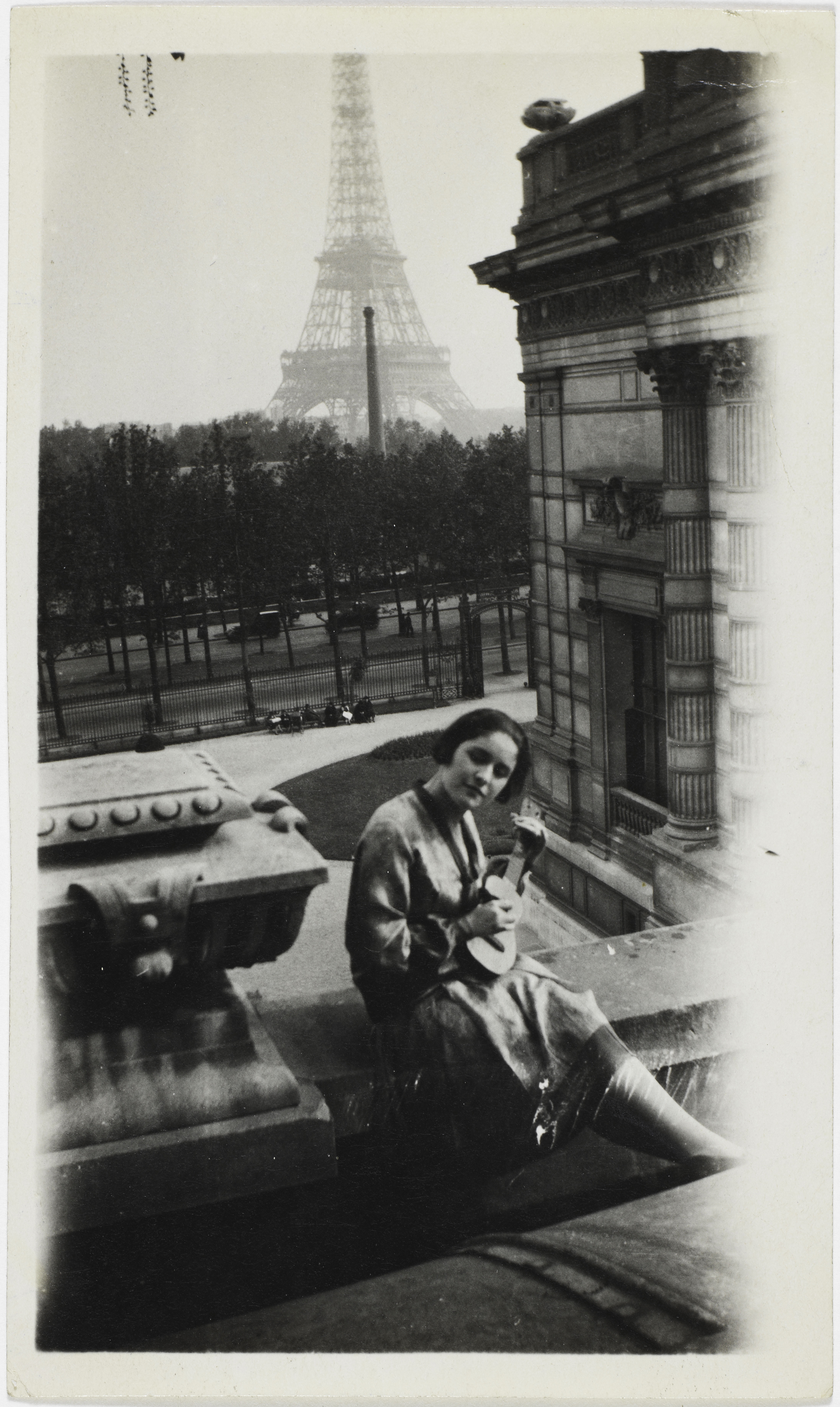

Dora Maar’s notebook. Photo by Roxane Lagache. Courtesy of Éditions Stock.

To summarize: a woman, a painter, with strong ties to the Surrealist movement, psychoanalyzed by Lacan, and associated with the greatest of the great. If one wanted to quibble, four or five of the century’s giants were missing here: Picasso, Matisse, Dalí, Miró, René Char. But more important than those missing was the missing owner: the woman who held the pen and gave us this photograph of her world in twenty pages. Sometimes she made spelling mistakes or got names wrong: she wrote Rochechaure instead of Rochechouart, Leiris with a y, and Alice Toklace rather than Toklas. She was a foreigner, or dyslexic.

At first, she made an effort. Each page begins with a list of carefully written names—always using the same pen—undoubtedly copied from an earlier address book. The letters are even, somewhat rounded, the stroke energetic but neat. And then, after a few lines, the handwriting becomes confused and disorderly. These were the new contacts for the year 1951 whose numbers she added later, scribbling them down, one hand holding the phone, the other reaching for the closest pencil. Or maybe that day she was more irritated, or tired, or in a hurry.

At a used-book stall, I discovered an enormous 1952 phone directory. It weighed at least five kilos and had a weathered orange cloth cover with advertisements printed on the spine. With this new resource, I cross-checked the names and addresses in the address book to compare and verify them. Jacques Lacan’s number did correspond to the one in the book: LACAN, physician, 30, rue de Lille, LIT 3001. But BLONDIN, avenue de la Grande Armée, with the same name as the writer, was a surgeon. There were at least three other numbers for doctors. More surprising: TRILLAT, graphologist. So the owner was curious about other kinds of analysis. More frivolous: a beauty parlor, a furrier on boulevard Saint-Germain. I was beginning to imagine a stylish artist, maybe very beautiful as well. MICOMEX, rue de Richelieu, import-export: she must have needed to ship her paintings. I went back and forth between directory and address book. From address book to Google. From Google to Wikipedia. Each tiny discovery seemed like a victory.

But some names remained indecipherable or elusive. Camille? Katell? Paulette? Lorraine? Madeleine? Women’s first names, jotted down to be read only by the one who wrote them and knew them so well that the surnames were superfluous. I was reminded of Patrick Modiano’s remark, trying to track down Dora Bruder: “Often, what I know about them amounts to no more than a simple address. And such topographical precision contrasts with what we shall never know about their life—this blank, this mute block of the unknown.”

Achille de MÉNERBES also remained a mystery. She had noted his address, 22, rue Petite Fusterie, in Avignon, and his telephone number, 2258. But seventy years later, it was as if this man never existed. He had left not a trace. Why linger over this name? If I were sensible, I would move on to the next one. Nevertheless, this Achille was like a band-aid stuck to my fingers—good thing it wouldn’t let go! Suddenly, under the magnifying glass, the letters fell into place. I had been reading too quickly or not carefully enough. She hadn’t written “Achille de” at all, but “Architecte”!

“Architecte Ménerbes.” She must have owned a house in this village in the Luberon, and she must have needed an architect from Avignon to supervise the work. My fingers trembled as they punched out the letters on my computer keyboard. The Wikipedia page on Ménerbes revealed that only two painters spent time there in the early 1950s. I automatically eliminated Nicolas de Staël, since he appeared among the contacts. The second name was that of a woman: painter, photographer, driving force behind the Surrealists, close friend of Éluard and Balthus, analyzed by Lacan. Of course, it must be her! Everything fit, it all matched, up to Picasso’s absence at the letter P. In 1951, six years after their breakup, she did not copy his address or his phone number into her new address book, not being able to erase him in any other way. Maybe this wasn’t “a Picasso.” But it was the address book of Dora Maar that I held in my hand!

I think I remember letting out a cry, shrieking like a soccer player who has just scored a goal, yelling and making fists, screaming—bizarrely—“YES!” Then I called T.D. No answer. Stupid telephone! No one to shout to—“I found it!”

“First I find, then I seek,” said Picasso. That was exactly what I was going to do—seek to understand.

Dora Maar’s notebook. Photo by Roxane Lagache. Courtesy of Éditions Stock.

Theodora Markovitch

6 rue de Savoie

Paris

Dora Maar. At first, only the photographs came to mind: Picasso naked to the waist, Picasso in his striped swimming trunks, Picasso painting Guernica . . . And then, all those paintings he did of her, depicting her as “the weeping woman,” disfigured, devastated by grief.

Thank goodness for Google. I surfed, I clicked, I did not read so much as devour: “Dora Maar, French photographer and painter, Picasso’s mistress . . .” “Dora Maar, from her given name Henriette Theodora Markovitch, born November 22, 1907, in Paris . . .” “Only daughter of a Croatian architect and Touranian mother . . .” “Spent her childhood in Argentina before returning to live in France . . .” “Friend of André Breton and the Surrealists . . .” “Mistress of Georges Bataille . . .” Dates, cities, names. “Dora Maar, remarkable twentieth-century figure . . .” “Profoundly original style . . .” And always the references to Picasso: he “loved other women more passionately, but none had so much influence over him . . .” “Picasso pushed her to give up photography . . .” “Picasso left her for the younger Françoise Gilot . . .” Snippets from a life, flashes of suffering: institutionalized, electric shock treatment, psychoanalysis, God, solitude. So the woman who owned this address book had been Picasso’s companion for almost ten years, from 1936 to 1945. Before him, she had been a great photographer. After him, a painter who sank into madness, then mysticism, and finally reclusion.

I had fun making a list of the adjectives attached to her, hoping that a portrait would emerge from this cloud of words: beautiful, intelligent, shy, willful, volatile, quick-tempered, haughty, unyielding, impetuous, proud, cultivated, authoritarian, snobbish, vain, mystical, mad . . .

Most of the newspaper articles about her dated from her death in 1997 and the sale by auction of her estate: 213 million euros divided up among experts, auctioneers, genealogists, the state, and two distant heirs in France and Croatia who had never met her.

In the end, I wrote down this sentence, copied and pasted so often on the internet I don’t know how to credit it: “She was Pablo Picasso’s mistress and muse, a role that eclipsed the entirety of her work.” A cruel legacy that preserves only the role of mistress and casts an entire life’s art in the shadow of a giant. Cruel but irrevocable. Who knows Dora Maar’s work? Who remembers that she was one of the rare women photographers accepted among the Surrealists? Who recognizes that she devoted sixty years of her life to painting?

Her most famous photographs are the portraits of Picasso. But the most astonishing ones come earlier: dreamlike experiments, Surrealist collages, shots capturing social issues. Before she had even met the Spanish painter, she was more famous than her friends Brassaï and Cartier-Bresson, and she had not yet turned thirty. Even today, collectors and major museums fight over her prints at auctions. But that is not the case with her paintings, to which she attached much greater importance.

Many authors have already examined her fate: a few serious biographies, some novels loosely based on her life, and many art books. They are almost all written by women, fascinated by what became of her and the mystery of a tragic heroine who, like Camille Claudel or Adèle Hugo, devoted and abandoned herself to passion. And here I was, joining their ranks.

She must have started entering names in the address book in January 1951. In Paris, an icy wind was blowing from the north. It snowed for New Year’s Eve. On rue de Savoie it must have been very cold, especially since she had a tendency to scrimp on coal. From the leather writing case on her mahogany desk, she took one of the quill pens that Picasso had given her. Nothing had been moved in six years. She still slept in the Empire bed where they had made love and still lived among his gifts, his paintings, his sculptures, his little makeshift constructions that she stashed in drawers. Above all, she hadn’t repainted the walls; it would be sacrilege to cover over the insects that the master had drawn in the cracks to amuse himself.

I imagined her carefully filling the small booklet page by page. She would have begun with the As, then moved on to the Bs. But without strictly following alphabetical order. She must have used this occasion to make a selection; the friends who betrayed her no longer warranted an entry. Sometimes she hesitated: What was the use? Sometimes she kept them as one keeps a photo or a memento. The hardest to eliminate were the deceased, who must have seemed like ghosts from the oldest address books. By deleting their names, she buried them one more time.

This address book was a snapshot of her world in 1951: layers of friends and acquaintances accumulated over the years, and a few new ones, surely. But who really mattered in this list? Who telephoned her? What numbers did she dial? If someone found our smartphone contacts today, wouldn’t they see our favorites, reconstruct the history of our calls, read our texts and emails, listen to our messages? They would know our entire lives. This book of hers was silent as the grave. Nevertheless, it could speak of the delicate hands, fingernails forever polished, that slipped it into or retrieved it from her handbag. It could name her true friends. It could remember conversations, confidences, arguments, laughter, or tears, for which it was the only witness. It could also recall her moments of solitude, when it sat there closed, it and the cat her only companions.

This excerpt is from the new publication Finding Dora Maar: An Artist, an Address Book, a Life by Brigitte Benkemoun and translated by Jody Gladding © 2020 J. Paul Getty Trust.