Last weekend, a blockbuster exhibition of previously unseen paintings on cardboard by Jean-Michel Basquiat opened at Florida’s Orlando Museum of Art (OMA). The occasion marks the latest chapter in an improbable story for the artworks, which sat in a neglected Los Angeles storage unit for years before being sold at auction to a pair of savvy treasure hunters.

Experts, however, have quietly debated the authenticity of the paintings—including one example that features a FedEx logo not used by the company until six years after the artist’s death, according to the New York Times, which first reported the story. Now, some claim the museum is gambling with its reputation in displaying them.

“Heroes and Monsters,” as the show is called, has proved a big hit with locals so far, the OMA’s director and chief executive, Aaron De Groft, said in an interview with Artnet News. “We had 4,000 people over the two opening nights, and since that time, average attendance is up 500 percent,” he said.

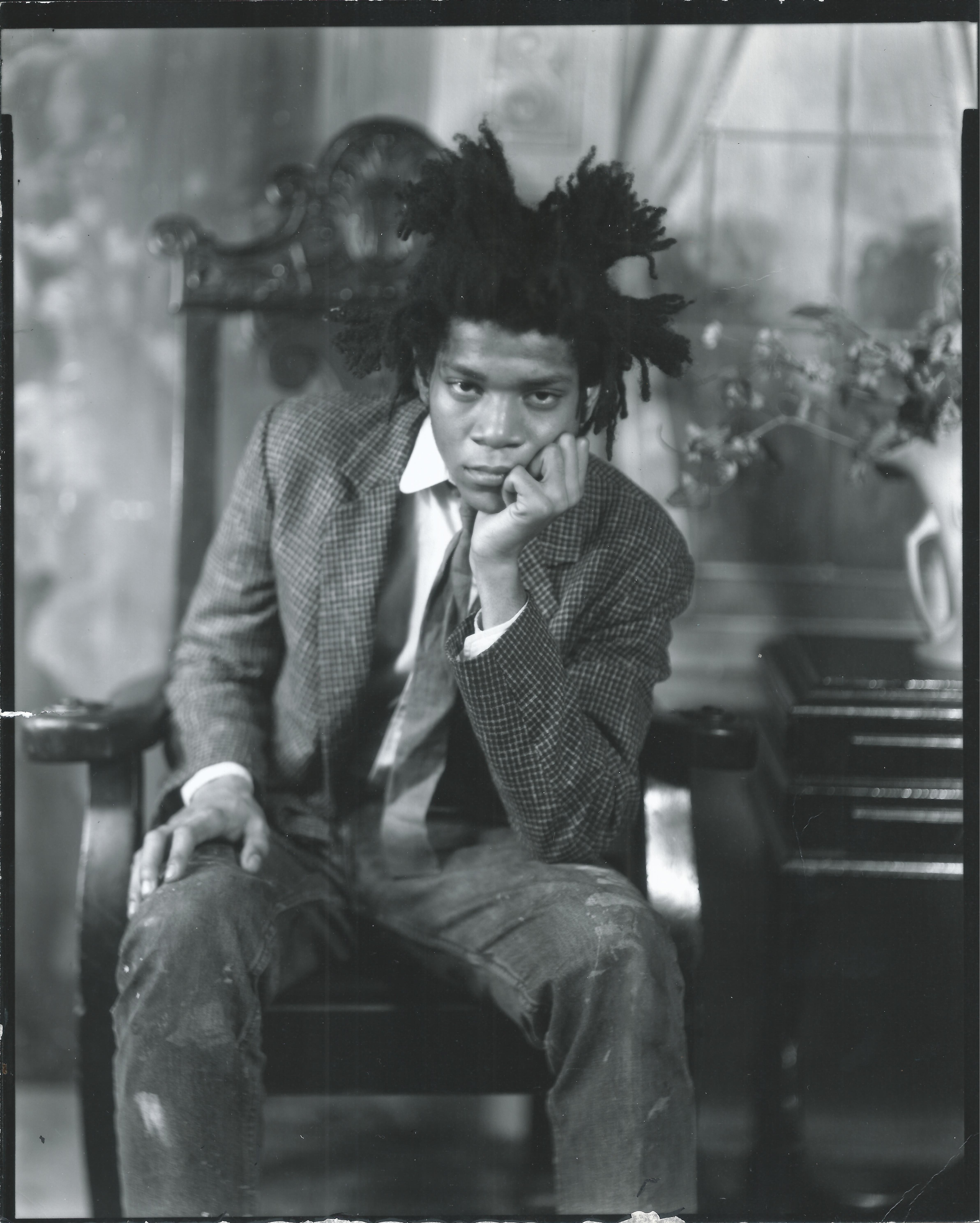

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Industry Insider/Big Head with TV) (1982).Courtesy of the Orlando Museum of Art.

The presentation features 25 cardboard artworks said to have been created by Basquiat in 1982, while he was just 22, living and working in a studio space in Larry Gagosian’s home in Los Angeles. Strapped for cash, the artist supposedly sold the lot directly to television screenwriter Thad Mumford (whose credits include M*A*S*H) for $5,000.

There is no record of the paintings again until 2012, when the contents of an unpaid storage unit kept by Mumford were auctioned off. With the help of a financial backer, a local storage hunter named William Force picked up the paintings for roughly $15,000.

Force and his backer, Lee Mangin, have tried to sell the artworks since, and in their pursuit have mustered up compelling evidence.

After a 2017 forensic investigation, a handwriting expert found that the signature on the paintings was indeed the artist’s. That same year, Basquiat scholar Jordana Moore Saggese weighed in, agreeing that the artworks were legitimate. In 2018 and ‘19, a founding member of the Basquiat estate’s authentication committee, curator Diego Cortez, came to the same conclusion. (The authentication committee has since been disbanded, and Cortez is deceased.)

Installation view of “Heroes & Monsters: Jean-Michel Basquiat, The Thaddeus Mumford, Jr. Venice Collection” at the Orlando Museum of Art, 2022. Courtesy of the Orlando Museum of Art.

And yet despite these approvals and the art market’s hunger for fresh Basquiat material, Force and Mangin have yet to find a buyer—an indication, perhaps, of how the market views the works’ legitimacy.

De Groft said that, in planning the exhibition, he reviewed and approved the reports put forth by Force and Mangin. The museum is also publishing a show catalogue with several new essays on the 25 artworks.

“We’re not defensive here,” said the director, who took up his post a year ago this month. “We’re confident in not only the work we did and our rigorous standards, but also the work that got done before by superstars in the Basquiat world.”

“You know what’s funny?” De Groft went on. “No one has said these paintings are not by Basquiat.”

This is true—few have publicly dismissed the paintings. But silence is not uncommon when it comes to contested authentication cases, in which outspoken “experts” can be implicated in messy lawsuits. One such case indirectly led to the Basquiat authentication committee’s dissolution in 2012.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (One More King/Czar) (1982). Courtesy of the Orlando Museum of Art.

Others at the museum don’t share De Groft’s confidence, it seems. An unnamed source at the institution told the Times that the “show raised red flags” for members of the curatorial staff, but De Groft did not heed their apprehension.

Of particular concern for the curators was the issue of the FedEx logo. On the reverse side of one work, painted on a piece of salvaged cardboard, a printed set of instructions from the company reads “Align top of FedEx Shipping Label here.” The person responsible for that version of the FedEx box design, brand expert Lindon Leader, told the Times that it wasn’t created until 1994—12 years after the artworks were said to have been completed, and six after Basquiat’s death.

When asked about this discrepancy, De Groft said that the box in the exhibition doesn’t feature the hallmarks of the 1994 FedEx redesign.

“I’m just going to stand by our hard work,” he said. “These [paintings] were already authenticated. You have one person talking about the font on a box—it is what it is. But it’s wrong.” He also categorically denied a local report suggesting that the museum placed a gag order on its staffers regarding the Basquiat exhibition and that several OMA computers have been seized by the FBI for investigation.