In 1540, Andreas Vesalius began dissecting bodies. This broke from medical orthodoxy that dictated physicians follow the teachings of Aristotle, Galen, and co. However, as Vesalius discovered and dogmatically spelled out in his 1543 book On the Structure of the Human Body, these ancient Greek texts were riddled with inaccuracies.

Vesalius subverted the medical establishment, provoking scorn, praise, imitation, and eventually a position in the court of Emperor Charles V. The impact is proclaimed in the work’s intricate woodcut frontispiece: a lecture hall crammed with men who jostle and crane to watch the master of anatomy at work.

The Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. might be hoping for a similar, if more orderly, response to “Imprints in Time,” an epicurean selection of 52 books and manuscripts—including a first edition Vesalius—drawn from the collection of Stuart and Mimi Rose that celebrates mankind’s eternal pursuit of knowledge.

Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica (1543). Photo courtesy Folger Shakespeare Library.

It’s the Library’s first public offering following a four-year, $80-million expansion that involved excavating beneath the Tudor-style Great Hall to create 6000-square-feet of exhibition space. One prerogative was to take all 82 copies of Shakespeare’s First Folio out of storage and onto permanent display. Another was to create a space suitable for displaying sensitive manuscripts, whether paper, vellum, papyri, or silk.

“In the past, we had to use the Great Hall, which has high vaulted ceilings and enormous windows,” said Greg Prickman, the Folger’s director of collections who curated “Imprints in Time” alongside Rose. “Now we are in complete control of the environment.”

The Missal of Etienne de Longwy (1490). Photo courtesy of Folger Shakespeare Library.

It was Rose, in his capacity as a longtime Folger board member, who pushed hard for what he called “the great dig,” one allowing the museum to exhibit rare books, both from its own collection and beyond. As Rose told it, he got the collecting bug after ambling into Sotheby’s one day and buying books that, though interesting, “weren’t of great quality.” Soon after, he acquired a first folio of Nicolaus Copernicus’s heliocentric theory of the cosmos, De revolutionibus (one sold for $3 million in 2016). He said he’s been “filling in the middle ever since.”

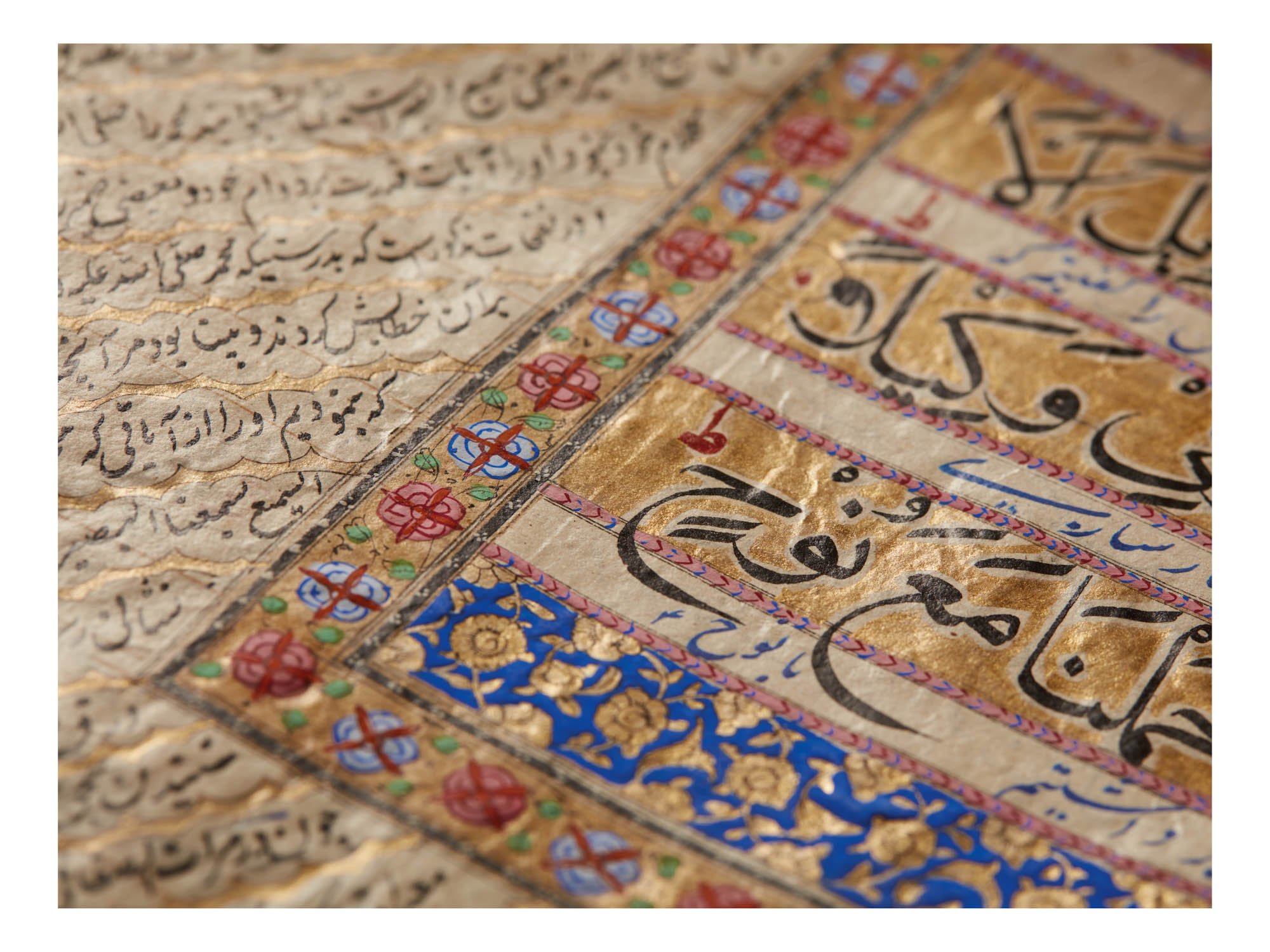

This “middle” spans thousands of texts, traversing illuminated Medieval manuscripts, ancient Egyptian papyri, annotated manuscripts of classic novels, and everything in between. Which raises a tricky curatorial question: how to create a narrative out of such an omnivorous collection? The simple answer: you don’t.

Instead, in the low atmospheric lighting of its new gallery, “Imprints in Time” seeks to create the experience of being welcomed into a great collector’s library. The excitement, Prickman said, comes from not knowing what you’re going to discover next.

“We wanted to display things people would know and be interested in, to show a sweep of history and to take people through the development of the book,” Prickman said. “It’s a way of seeing things without bringing a lot of expectation.” Visitors are free to create their own connections, conjure their own narratives.

Nicolaus Copernicus, De revolutionibus (1543). Photo courtesy Folger Shakespeare Library.

All the same, there are rhythms and echoes at play, moments in which the manuscripts are in dialogue. One arrives with Copernicus’s 1543 text that places circular planetary orbits around a static dot marked “sol.” It sparked a scientific revolution joined by Johannes Kepler’s Astronomia Nova that stated orbits were elliptical and later Galileo Galilei, whose Dialogo in defense of Copernicus saw him tried for heresy and confined to house arrest. Here, its frontispiece sees Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Copernicus, locked in intense discussion.

Galileo Galilei, Dialogo (1638). Photo courtesy Folger Shakespeare Library.

Elsewhere, there’s the sense of a forever expanding world. Begin, if you like, with Christopher Columbus’s letter to Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castille who funded his westward voyage after French, Portuguese, and English monarchs refused. The popularity of Americanum prompted a hasty second edition, complete with six woodcut illustrations that evidence in a timid huddle of naked men, the burgeoning prejudices of European colonialism.

The thread continues with Theodor de Bry’s Grand Voyages that includes the first description of Virginia and North Carolina. Drawings from Cesare Vecellio (Titian’s cousin and workshop assistant) update the European impression of the inhabitants of the Americas.

Christopher Columbus, Americanum no. 1 (1494). Photo courtesy Folger Shakespeare Library.

On the literature front, numerous annotated and inscribed editions pull authors off the shelf and into life. The proofs for Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter are carefully marked with dashes and circles, Charles Dickens offers his “high admiration” to Victorian contemporary George Eliot in a gift of A Tale of Two Cities, and Frederick Douglass confirms Narrative was written “by himself,” charming given today’s proclivity for ghostwriters.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings (1954–55). Photo courtesy Folger Shakespeare Library.

If a goal of “Imprints in Time” is to the share the excitement of rare books and manuscripts with a wider public, one such moment arrives with the galley proofs of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. The prologue’s famous description of the ring sees Tolkien cross out “shadows” and replace it with “darkness,” offering the visitor a sense of great literature rewritten before our very eyes.

“Imprints in Time” is on view at the Folger Shakespeare Library, 201 East Capitol Street, SE Washington, D.C., through January 5, 2025.