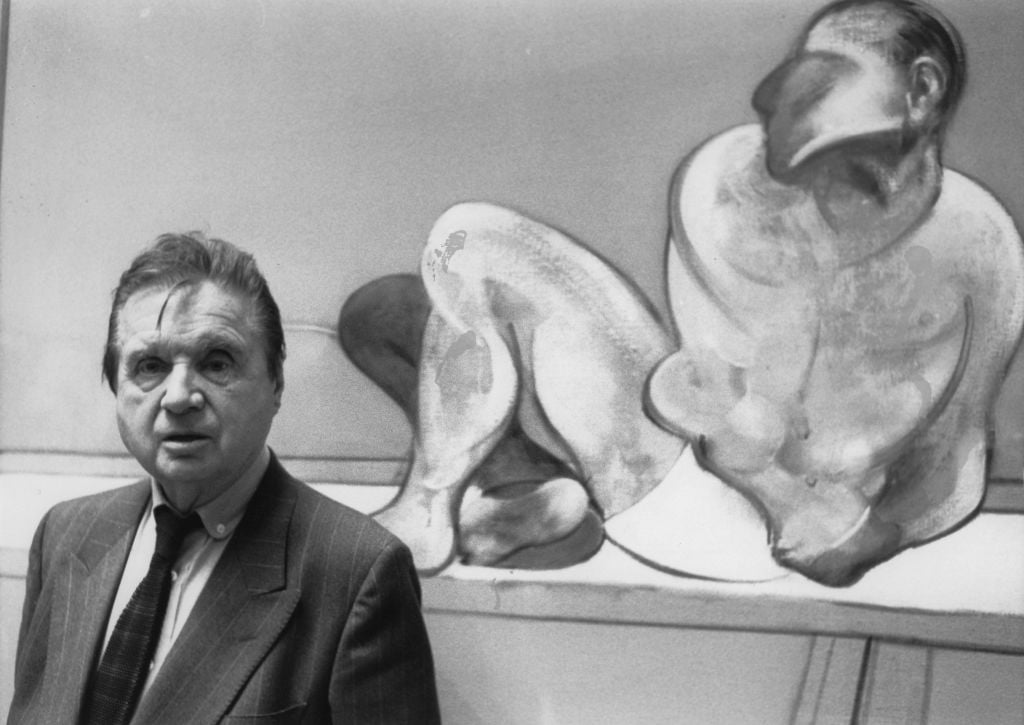

A onetime friend of Francis Bacon who donated an archive of materials from the artist’s studio to Tate has threatened to withdraw the gift because, he claims, the gallery has failed to prominently display it.

Barry Joule, a handyman who got to know Bacon in the late 1970s, donated more than 1,200 sketches, photographs, and documents from Bacon’s London studio at 7 Reece Mews in 2004. The trove was estimated to be worth £20 million at the time. Now, criticizing the institution for keeping the works in storage, Joule has suggested that his generosity might be better appreciated by a museum in France.

In an email sent to Tate director Maria Balshaw on August 3, Joule threatened to sue the gallery for the return of the works, the Guardian reported. The threat has come after years of back-and-forth between Joule and the gallery in which the collector expressed his dissatisfaction that the materials had not been the subject of a major exhibition.

Tate, for its part, claims it abided by the terms laid out in the donation contract, which required it to catalogue and display the works. Since 2004, the materials have been available for public access in its archive, and items were exhibited in a display at Tate Britain in 2019, though they were notably left out of the gallery’s major Bacon exhibition in 2008.

Joule says that’s unacceptable. He contends that Tate curators implied that the materials, which include an oil painting, Study for Head of William Blake, would be suitable for a more prominent exhibition, but as time went on, “I was continually met with silence, ignored or just fobbed off.” Now, the collector is prepared to take legal action for the return of the donation “if a satisfactory conclusion is not reached… by October 2021.”

Joule also told the Guardian he is cancelling a promised bequest to the gallery: a 1936 Bacon self-portrait and nine other paintings from the same period along with other artwork, letters, books, and tape recordings.

The issue of donors withdrawing promised gifts is a nightmare for museums—and one that is growing in frequency. Collectors who stand to profit from skyrocketing contemporary-art prices are increasingly reneging on pledged donations. A spokesperson for Tate told Artnet News that it has proposed a meeting with Joule in September.

There may be more to Tate’s reluctance to prominently display Joule’s materials than mere curatorial preference. The artist’s estate has cast doubt on the authenticity of the archive, and none of its material was included in Bacon’s 2016 catalogue raisonné. Contacted by Artnet News, a representative for the estate pointed to a recent publication that includes an essay by researcher Sophie Pretorius, who concluded that the archive’s materials were not consistent with the rest of Bacon’s oeuvre.

Pretorius wrote that the story of the Joule material is “riddled with exaggeration, half-truths, and contradictions.” She added that a combination of “Bacon’s soaring prices, his tantalizing obtuseness regarding sketches, and the relative lack of comparative material against which to measure this material helped create the perfect storm.”

In 2002, then-Tate director Nicolas Serota wrote in a letter accepting the donation that while most of the papers and collages had “probably” come from the Bacon studio, “the majority are by other hands.” More recently, according to Pretorius, a Tate curator said the institution would consider “a more direct pronouncement” about Bacon’s involvement in the material in light of her research.

Joule, who has also claimed he is the unidentified subject in Bacon’s acclaimed series of cricket paintings, met the artist in 1978; they remained friends until his death in 2004. He said that Bacon gifted him the archive shortly before the artist left for Spain in 1992, where he died from a heart attack.

Joule could not be reached by Artnet News. He has said he chose Tate as the destination for the archive because it had been Bacon’s favorite gallery. His donation of 80 Bacon drawings to the Musée Picasso in Paris was the subject of a major exhibition there in 2005. He told the Guardian that if he withdraws the trove from Tate, he intends to donate it to a museum in France, where he currently lives.

Notably, Pretorius’s research also references Bacon works in the Musée Picasso, the National Gallery of Canada, and other private collections, which she said are “consistent in style and technique” with those in the Joule archive, although not having studied them in person, she does not go as far as to suggest that they are not authentic.