July 6 was the 112th birthday of the great Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. To mark the occasion, the Frida Kahlo Corporation, the official licensing agent for commercial products bearing her name and likeness, unveiled a new Kahlo-branded makeup line, produced by Ulta Beauty and priced between $10 and $30. (The same week, Vans launched new line of shoes featuring her paintings.)

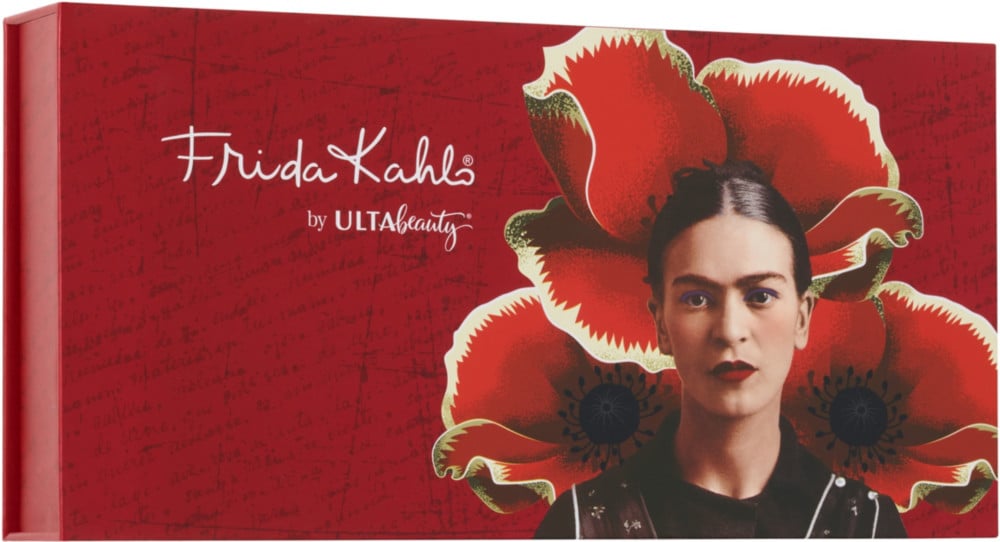

There was one major problem: The photo of Kahlo being used on the packaging, many felt, downplayed her famous unibrow, leaving the public to wonder whether or not the unconventional beauty had been Photoshopped to conform to traditional standards of attractiveness.

Ultra Beauty or Ultra Disrespect?

“Never apologize for who you are,” wrote the company. “Inspired by Frida’s strength, this collection is full of bold colors, bright lips, a glowy highlighter & more.”

But fans of the artist were quick to accuse the company of airbrushing her likeness to remove excess facial fair. The backlash was swift, with over 7,000 comments on Ulta Beauty’s Facebook post announcing the new products.

Ulta denied the charge. “Out of respect for her legacy, we partnered closely with the Frida Kahlo Corporation for more than a year on this collection. Together we selected assets from their official library that celebrate Frida’s beauty and spirit,” the company wrote in a comment on the original Facebook post. “The images of Frida are originals with no alteration to her likeness, including her signature unibrow.”

One reader responded with what appeared to be a black-and-white version of the colorized photo used in the ad campaign, noting it was from the 1920s, when Kahlo’s facial hair, which also included a distinct mustache, was less pronounced.

Still, the fact that the image is based on a real photo isn’t good enough for some fans, who believe that a picture of Kahlo that better highlighted her signature facial hair would have been a more representative choice. “If you wanted to truly honor her and make a statement in the beauty industry, you wouldn’t have used the one likeness that shows her in traditional beauty standards,” insisted one disappointed comment.

The Importance of Her Image

In many ways, the new make-up line is a perfect fit for Kahlo. “She had a special skill for applying makeup and achieving a natural look, and spent a lot of time on this effect,” her close friend Olga Campos once said. “She was always made-up and well dressed, even when she did not expect visitors.”

Kahlo’s physical appearance was an integral part of her work—so much so that there have been exhibitions featuring the artist’s clothing, cosmetics, and accessories.

The 2018 show “Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up,” originating at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, and the Brooklyn Museum’s expanded 2019 version, “Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving,” revealed never-before-seen personal effects from Casa Azul, Kahlo and husband Diego Rivera’s Mexico City home-turned-museum. The displays offered unexpected new insights into her life and work.

Revlon eyebrow pencil in ‘Ebony’ and emery boards with packaging; compact with blusher in ‘Clear Red’ and powderpuff; lipstick in ‘Everything’s Rosy’ by Revlon. Photograph by Javier Hinojosa. Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums. Museo Frida Kahlo.

Kahlo’s beauty regimen included Pond’s Dry Skin Cream, Coty’s loose rice powder, “Ravishing Rose” Revlon blush, red lipstick (the recent exhibition included the shade “Everything’s Rosy”), and a Revlon “Ebony” eyebrow pencil as well as black pigments by Talika that she would use to accentuate her unibrow and eyelashes. The show also included bottles of Kahlo’s nail polish, with colors like “Frosted Pink Snow” and “Raven Red.”

“In her lifetime, Frida Kahlo’s appearance was unconventional, and she did not try to disguise what she described as her masculine features,” Claire Wilcox, who co-curated the V&A show, told Vogue. “Her fearlessness and self-confidence has made her a role model for independent, free-thinking women who do not necessarily want to conform to societal norms of beauty.”

Frida Kahlo, Me and My Parrots (1941) ©2019 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Perhaps more than any artist of the 20th-century, Kahlo carefully crafted her self-image, masking her physical disability while celebrating her indigenous heritage and her androgyny. But that’s not at all evident in the woman being peddled by Ulta, which has dug up a photograph that reads as a soft-focus glamour shot of Kahlo, emphasizing her rosebud lips rather than her heavy brow.

It’s a far cry from how she depicted herself in her famed self portraits, or from what Kahlo once wrote of her own appearance: “Of my face, I like the eyebrows and the eyes. Aside from that, I like nothing… I have the mustache and in general the face of the opposite sex.”

The issue goes beyond the question of beauty standards—and the fact that the makeup set’s brow palette doesn’t even include black. Many also were quick to point out Kahlo’s Communist politics, which would seem to be firmly at odds with the commercialization of her image.

“To invoke Kahlo’s image is to tap into the Kahlo patina, to associate your brand with some of the many things that she symbolizes: resistance against adversity and oppression, feminism, and queerness among them,” wrote Sangeeta Singh-Kurtz for Quartzy, slamming Ulta for “slapping her doctored image on a makeup kit and selling it online for her birthday.”

The Frida Kahlo Corporation declined to comment on the controversy, directing artnet News to the official press release, in which a company spokesperson says that “this collection celebrates Frida and extends her positive impact and message of empowerment which allows fans everywhere to embrace life the way she did, and paint their own reality.”

A History of Controversy

Kahlo’s niece Isolda Pinedo Kahlo sold the rights to the painter’s trademark to the Frida Kahlo Corporation in 2005, two years before her death. Relationships between the Panama-based company and the artist’s family have deteriorated in recent years, with Pinedo Kahlo’s daughter, Mara Cristina Romeo Pinedo, speaking out against a controversial-but-licensed Kahlo Barbie doll, released by Mattel as part of its “Inspiring Women” line in 2018.

“I would have liked her to have a unibrow, for her clothes to be made by Mexican artisans,” Pinedo complained, insisting that Kahlo’s family retained the rights to her name and image. In April of last year, Pinedo won a temporary injunction blocking the doll’s sale in Mexico. The Frida Kahlo Corporation fired back the following month, suing Pinedo for attempting to discredit the company and for co-opting its licensing rights.

A Barbie doll depicting late Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. Photo by ALFREDO ESTRELLA/AFP/Getty Images.

Another legal dispute involving the corporation broke out last month, when Colorado artist Nina Shope sued the Frida Kahlo Corporation for getting her handmade Kahlo dolls removed from Etsy for alleged trademark infringement. Her complaint accuses the company of “deceptive and unfair trade practices.”